February 4, 2024

It’s crucial in investing to have the proper balance of confidence and humility. Overconfidence is very deep-seated in human nature. Nearly all of us tend to believe that we’re above average across a variety of dimensions, such as looks, smarts, academic ability, business aptitude, driving skill, and even luck (!).

Overconfidence is often harmless and it even helps in some areas. But when it comes to investing, if we’re overconfident about what we know and can do, eventually our results will suffer.

(Image by Wilma64)

The simple truth is that the vast majority of us should invest in broad market low-cost index funds. Buffett has maintained this argument for a long time: https://boolefund.com/warren-buffett-jack-bogle/

The great thing about investing in index funds is that you can outperform most investors, net of costs, over the course of several decades. This is purely a function of costs. A Vanguard S&P 500 index fund costs 2-3% less per year than the average actively managed fund. This means that, after a few decades, you’ll be ahead at least 80% (or more) of all active investors.

You can do better than a broad market index fund if you invest in a solid quantitative value fund. Such a fund can do at least 1-2% better per year, on average and net of costs, than a broad market index fund.

But you can do even better—at least 8% better per year than the S&P 500 index—by investing in a quantitative value fund focused on microcap stocks.

- At the Boole Microcap Fund, our mission is to help you do at least 8% better per year, on average, than an S&P 500 index fund. We achieve this by implementing a quantitative deep value approach focused on cheap micro caps with improving fundamentals. See: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

I recently re-read Common Stocks and Common Sense (Wiley, 2016), by Edgar Wachenheim III. It’s a wonderful book. Wachenheim is one of the best value investors. He and his team at Greenhaven Associates have produced 19% annual returns for over 25 years.

Wachenheim emphasizes that, due to certain behavioral attributes, he has outperformed many other investors who are as smart or smarter. As Warren Buffett has said:

Success in investing doesn’t correlate with IQ once you’re above the level of 125. Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.

That’s not to say IQ isn’t important. Most of the finest investors are extremely smart. Wachenheim was a Baker Scholar at Harvard Business School, meaning that he was in the top 5% of his class.

The point is that—due to behavioral factors such as patience, discipline, and rationality—top investors outperform many other investors who are as smart or smarter. Buffett again:

We don’t have to be smarter than the rest; we have to be more disciplined than the rest.

Buffett himself has always been extraordinarily patient and disciplined. There have been several times in Buffett’s career when he went for years on end without making a single investment.

Wachenheim highlights three behavioral factors that have helped him outperform others of equal or greater talent.

The bulk of Wachenheim’s book—chapters 3 through 13—is case studies of specific investments. Wachenheim includes a good amount of fascinating business history, some of which is mentioned here.

Outline for this blog post:

- Approach to Investing

- Being a Contrarian

- Probable Scenarios

- Controlling Emotions

- IBM

- Interstate Bakeries

- U.S. Home Corporation

- Centex

- Union Pacific

- American International Group

- Lowe’s

- Whirlpool

- Boeing

- Southwest Airlines

- Goldman Sachs

(Photo by Lsaloni)

APPROACH TO INVESTING

From 1960 through 2009 in the United States, common stocks have returned about 9 to 10 percent annually (on average).

The U.S. economy grew at roughly a 6 percent annual rate—3 percent from real growth (unit growth) and 3 percent from inflation (price increases). Corporate revenues—and earnings—have increased at approximately the same 6 percent annual rate. Share repurchases and acquisitions have added 1 percent a year, while dividends have averaged 2.5 percent a year. That’s how, on the whole, U.S. stocks have returned 9 to 10 percent annually, notes Wachenheim.

Even if the economy grows more slowly in the future, Wachenheim argues that U.S. investors should still expect 9 to 10 percent per year. In the case of slower growth, corporations will not need to reinvest as much of their cash flows. That extra cash can be used for dividends, acquisitions, and share repurchases.

Following Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, Wachenheim defines risk as the potential for permanent loss. Risk is not volatility.

Stocks do fluctuate up and down. But every time the market has declined, it has ultimately recovered and gone on to new highs. The financial crisis in 2008-2009 is an excellent example of large—but temporary—downward volatility:

The financial crisis during the fall of 2008 and the winter of 2009 is an extreme (and outlier) example of volatility. During the six months between the end of August 2008 and end of February 2009, the [S&P] 500 Index fell by 42 percent from 1,282.83 to 735.09. Yet by early 2011 the S&P 500 had recovered to the 1,280 level, and by August 2014 it had appreciated to the 2000 level. An investor who purchased the S&P 500 Index on August 31, 2008, and then sold the Index six years later, lived through the worst financial crisis and recession since the Great Depression, but still earned a 56 percent profit on his investment before including dividends—and 69 percent including the dividends that he would have received during the six-year period. Earlier, I mentioned that over a 50-year period, the stock market provided an average annual return of 9 to 10 percent. During the six-year period August 2008 through August 2014, the stock market provided an average annual return of 11.1 percent—above the range of normalcy in spite of the abnormal horrors and consequences of the financial crisis and resulting deep recession.

(Photo by Terry Mason)

Wachenheim notes that volatility is the friend of the long-term investor. The more volatility there is, the more opportunity to buy at low prices and sell at high prices.

Because the stock market increases on average 9 to 10 percent per year and always recovers from declines, hedging is a waste of money over the long term:

While many investors believe that they should continually reduce their risks to a possible decline in the stock market, I disagree. Every time the stock market has declined, it eventually has more than fully recovered. Hedging the stock market by shorting stocks, or by buying puts on the S&P 500 Index, or any other method usually is expensive, and, in the long run, is a waste of money.

Wachenheim describes his investment strategy as buying deeply undervalued stocks of strong and growing companies that are likely to appreciate significantly due to positive developments not yet discounted by stock prices.

Positive developments can include:

- a cyclical upturn in an industry

- an exciting new product or service

- the sale of a company to another company

- the replacement of a poor management with a good one

- a major cost reduction program

- a substantial share repurchase program

If the positive developments do not occur, Wachenheim still expects the investment to earn a reasonable return, perhaps close to the average market return of 9 to 10 percent annually. Also, Wachenheim and his associates view undervaluation, growth, and strength as providing a margin of safety—protection against permanent loss.

Wachenheim emphasizes that at Greenhaven, they are value investors not growth investors. A growth stock investor focuses on the growth rate of a company. If a company is growing at 15 percent a year and can maintain that rate for many years, then most of the returns for a growth stock investor will come from future growth. Thus, a growth stock investor can pay a high P/E ratio today if growth persists long enough.

Wachenheim disagrees with growth investing as a strategy:

…I have a problem with growth-stock investing. Companies tend not to grow at high rates forever. Businesses change with time. Markets mature. Competition can increase. Good managements can retire and be replaced with poor ones. Indeed, the market is littered with once highly profitable growth stocks that have become less profitable cyclic stocks as a result of losing their competitive edge. Kodak is one example. Xerox is another. IBM is a third. And there are hundreds of others. When growth stocks permanently falter, the price of their shares can fall sharply as their P/E ratios contract and, sometimes, as their earnings fall—and investors in the shares can suffer serious permanent loss.

Many investors claim that they will be able to sell before a growth stock seriously declines. But very often it’s difficult to determine whether a company is suffering from a temporary or permanent decline.

Wachenheim observes that he’s known many highly intelligent investors—who have similar experiences to him and sensible strategies—but who, nonetheless, haven’t been able to generate results much in excess of the S&P 500 Index. Wachenheim says that a key point of his book is that there are three behavioral attributes that a successful investor needs:

In particular, I believe that a successful investor must be adept at making contrarian decisions that are counter to the conventional wisdom, must be confident enough to reach conclusions based on probabilistic future developments as opposed to extrapolations of recent trends, and must be able to control his emotions during periods of stress and difficulties. These three behavioral attributes are so important that they merit further analysis.

BEING A CONTRARIAN

(Photo by Marijus Auruskevicius)

Most investors are not contrarians because they nearly always follow the crowd:

Because at any one time the price of a stock is determined by the opinion of the majority of investors, a stock that appears undervalued to us appears appropriately valued to most other investors. Therefore, by taking the position that the stock is undervalued, we are taking a contrarian position—a position that is unpopular and often is very lonely. Our experience is that while many investors claim they are contrarians, in practice most find it difficult to buck the conventional wisdom and invest counter to the prevailing opinions and sentiments of other investors, Wall Street analysts, and the media. Most individuals and most investors simply end up being followers, not leaders.

In fact, I believe that the inability of most individuals to invest counter to prevailing sentiments is habitual and, most likely, a genetic trait. I cannot prove this scientifically, but I have witnessed many intelligent and experienced investors who shunned undervalued stocks that were under clouds, favored fully valued stocks that were in vogue, and repeated this pattern year after year even though it must have become apparent to them that the pattern led to mediocre results at best.

Wachenheim mentions a fellow investor he knows—Danny. He notes that Danny has a high IQ, attended an Ivy League university, and has 40 years of experience in the investment business. Wachenheim often describes to Danny a particular stock that is depressed for reasons that are likely temporary. Danny will express his agreement, but he never ends up buying before the problem is fixed.

In follow-up conversations, Danny frequently states that he’s waiting for the uncertainty to be resolved. Value investor Seth Klarman explains why it’s usually better to invest before the uncertainty is resolved:

Most investors strive fruitlessly for certainty and precision, avoiding situations in which information is difficult to obtain. Yet high uncertainty is frequently accompanied by low prices. By the time the uncertainty is resolved, prices are likely to have risen. Investors frequently benefit from making investment decisions with less than perfect knowledge and are well rewarded for bearing the risk of uncertainty. The time other investors spend delving into the last unanswered detail may cost them the chance to buy in at prices so low that they offer a margin of safety despite the incomplete information.

PROBABLE SCENARIOS

(Image by Alain Lacroix)

Many (if not most) investors tend to extrapolate recent trends into the future. This usually leads to underperforming the market. See:

- Werner De Bondt and Richard Thaler (1985), “Does the Stock Market Overreact?”: https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/Richard.Thaler/research/pdf/DoesStockMarketOverreact.pdf

- Josef Lakonishok, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny (1994), “Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation, and Risk”: http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/contrarianinvestment.pdf

The successful investor, by contrast, is a contrarian who can reasonably estimate future scenarios and their probabilities of occurrence:

Investment decisions seldom are clear. The information an investor receives about the fundamentals of a company usually is incomplete and often is conflicting. Every company has present or potential problems as well as present or future strengths. One cannot be sure about the future demand for a company’s products or services, about the success of any new products or services introduced by competitors, about future inflationary cost increases, or about dozens of other relevant variables. So investment outcomes are uncertain. However, when making decisions, an investor often can assess the probabilities of certain outcomes occurring and then make his decisions based on the probabilities. Investing is probabilistic.

Because investing is probabilitistic, mistakes are unavoidable. A good value investor typically will have at least 33% of his or her ideas not work, whether due to an error, bad luck, or an unforeseeable event. You have to maintain equanimity despite inevitable mistakes:

If I carefully analyze a security and if my analysis is based on sufficiently large quantities of accurate information, I always will be making a correct decision. Granted, the outcome of the decision might not be as I had wanted, but I know that decisions always are probabilistic and that subsequent unpredictable changes or events can alter outcomes. Thus, I do my best to make decisions that make sense given everything I know, and I do not worry about the outcomes. An analogy might be my putting game in golf. Before putting, I carefully try to assess the contours and speed of the green. I take a few practice strokes. I aim the putter to the desired line. I then putt and hope for the best. Sometimes the ball goes in the hole…

CONTROLLING EMOTION

(Photo by Jacek Dudzinski)

Wachenheim:

I have observed that when the stock market or an individual stock is weak, there is a tendency for many investors to have an emotional response to the poor performance and to lose perspective and patience. The loss of perspective and patience often is reinforced by negative reports from Wall Street and from the media, who tend to overemphasize the significance of the cause of the weakness. We have an expression that aiplanes take off and land every day by the tens of thousands, but the only ones you read about in the newspapers are the ones that crash. Bad news sells. To the extent that negative news triggers further selling pressures on stocks and further emotional responses, the negativism tends to feed on itself. Surrounded by negative news, investors tend to make irrational and expensive decisions that are based more on emotions than on fundamentals. This leads to the frequent sale of stocks when the news is bad and vice versa. Of course, the investor usually sells stocks after they already have materially decreased in price. Thus, trading the market based on emotional reactions to short-term news usually is expensive—and sometimes very expensive.

Wachenheim agrees with Seth Klarman that, to a large extent, many investors simply cannot help making emotional investment decisions. It’s part of human nature. People overreact to recent news.

I have continually seen intelligent and experienced investors repeatedly lose control of their emotions and repeatedly make ill-advised decisions during periods of stress.

That said, it’s possible (for some, at least) to learn to control your emotions. Whenever there is news, you can learn to step back and look at your investment thesis. Usually the investment thesis remains intact.

IBM

(IBM Watson by Clockready, Wikimedia Commons)

When Greenhaven purchases a stock, it focuses on what the company will be worth in two or three years. The market is more inefficient over that time frame due to the shorter term focus of many investors.

In 1993, Wachenheim estimated that IBM would earn $1.65 in 1995. Any estimate of earnings two or three years out is just a best guess based on incomplete information:

…having projections to work with was better than not having any projections at all, and my experience is that a surprisingly large percentage of our earnings and valuation projections eventually are achieved, although often we are far off on the timing.

The positive development Wachenheim expected was that IBM would announce a concrete plan to significantly reduce its costs. On July 28, 1993, the CEO Lou Gerstner announced such a plan. When IBM’s shares moved up from $11½ to $16, Wachenheim sold his firm’s shares since he thought the market price was now incorporating the expected positive development.

Selling IBM at $16 was a big mistake based on subsequent developments. The company generated large amounts of cash, part of which it used to buy back shares. By 1996, IBM was on track to earn $2.50 per share. So Wachenheim decided to repurchase shares in IBM at $24½. Although he was wrong to sell at $16, he was right to see his error and rebuy at $24½. When IBM ended up doing better than expected, the shares moved to $48 in late 1997, at which point Wachenheim sold.

Over the years, I have learned that we can do well in the stock market if we do enough things right and if we avoid large permanent losses, but that it is impossible to do nearly everything right. To err is human—and I make plenty of errors. My judgment to sell IBM’s shares in 1993 at $16 was an expensive mistake. I try not to fret over mistakes. If I did fret, the investment process would be less enjoyable and more stressful. In my opinion, investors do best when they are relaxed and are having fun.

Finding good ideas takes time. Greenhaven rejects the vast majority of its potential ideas. Good ideas are rare.

INTERSTATE BAKERIES

(Photo of a bakery by Mohylek, Wikimedia Commons)

Wachenheim discovered that Howard Berkowitz bought 12 percent of the outstanding shares of Interstate Bakeries, became chairman of the board, and named a new CEO. Wachenheim believed that Howard Berkowitz was an experienced and astute investor. In 1967, Berkowitz was a founding partner of Steinhardt, Fine, Berkowitz & Co., one of the earliest and most successful hedge funds. Wachenheim started analyzing Interstate in 1985 when the stock was at about $15:

Because of my keen desire to survive by minimizing risks of permanent loss, the balance sheet then becomes a good place to start efforts to understand a company. When studying a balance sheet, I look for signs of financial and accounting strengths. Debt-to-equity ratios, liquidity, depreciation rates, accounting practices, pension and health care liabilities, and ‘hidden’ assets and liabilities all are among common considerations, with their relative importance depending on the situation. If I find fault with a company’s balance sheet, especially with the level of debt relative to the assets or cash flows, I will abort our analysis, unless there is a compelling reason to do otherwise.

Wachenheim looks at management after he is done analyzing the balance sheet. He admits that he is humble about his ability to assess management. Also, good or bad results are sometimes due in part to chance.

Next Wachenheim examines the business fundamentals:

We try to understand the key forces at work, including (but not limited to) quality of products and services, reputation, competition and protection from future competition, technological and other possible changes, cost structure, growth opportunities, pricing power, dependence on the economy, degree of governmental regulation, capital intensity, and return on capital. Because we believe that information reduces uncertainty, we try to gather as much information as possible. We read and think—and we sometimes speak to customers, competitors, and suppliers. While we do interview the managements of the companies we analyze, we are wary that their opinions and projections will be biased.

Wachenheim reveals that the actual process of analyzing a company is far messier than you might think based on the above descriptions:

We constantly are faced with incomplete information, conflicting information, negatives that have to be weighed against positives, and important variables (such as technological change or economic growth) that are difficult to assess and predict. While some of our analysis is quantitative (such as a company’s debt-to-equity ratio or a product’s share of market), much of it is judgmental. And we need to decide when to cease our analysis and make decisions. In addition, we constantly need to be open to new information that may cause us to alter previous opinions or decisions.

Wachenheim indicates a couple of lessons learned. First, it can often pay off when you follow a capable and highly incentivized business person into a situation. Wachenheim made his bet on Interstate based on his confidence in Howard Berkowitz. Interstate’s shares were not particularly cheap.

Years later, Interstate went bankrupt because they took on too much debt. This is a very important lesson. For any business, there will be problems. Working through difficulties often takes much longer than expected. Thus, having low or no debt is essential.

U.S. HOME CORPORATION

(Photo by Dwight Burdette, Wikimedia Commons)

Wachenheim describes his use of screens:

I frequently use Bloomberg’s data banks to run screens. I screen for companies that are selling for low price-to-earnings (PE) ratios, low prices to revenues, low price-to-book values, or low prices relative to other relevant metrics. Usually the screens produce a number of stocks that merit additional analyses, but almost always the additional analyses conclude that there are valid reasons for the apparent undervaluations.

Wachenheim came across U.S. Home in mid-1994 based on a discount to book value screen. The shares appeared cheap at 0.63 times book and 6.8 times earnings:

Very low multiples of book and earnings are adrenaline flows for value investors. I eagerly decided to investigate further.

Later, although U.S. Home was cheap and produced good earnings, the stock price remained depressed. But there was a bright side because U.S. Home led to another homebuilder idea…

CENTEX CORPORATION

(Photo by Steven Pavlov, Wikimedia Commons)

After doing research and constructing a financial model of Centex Corporation, Wachenheim had a startling realization: the shares would be worth about $63 a few years in the future, and the current price was $12. Finally, a good investment idea:

…my research efforts usually are tedious and frustrating. I have hundreds of thoughts and I study hundreds of companies, but good investment ideas are few and far between. Maybe only 1 percent or so of the companies we study ends up being part of our portfolios—making it much harder for a stock to enter our portfolio than for a student to enter Harvard. However, when I do find an exciting idea, excitement fills the air—a blaze of light that more than compensates for the hours and hours of tedium and frustration.

Greenhaven typically aims for 30 percent annual returns on each investment:

Because we make mistakes, to achieve 15 to 20 percent average returns, we usually do not purchase a security unless we believe that it has the potential to provide a 30 percent or so annual return. Thus, we have very high expectations for each investment.

In late 2005, Wachenheim grew concerned that home prices had gotten very high and might decline. Many experts, including Ben Bernanke, argued that because home prices had never declined in U.S. history, they were unlikely to decline. Wachenheim disagreed:

It is dangerous to project past trends into the future. It is akin to steering a car by looking through the rearview mirror…

UNION PACIFIC

(Photo by Slambo, Wikimedia Commons)

After World War II, the construction of the interstate highway system gave trucks a competitive advantage over railroads for many types of cargo. Furthermore, fewer passengers took trains, partly due to the interstate highway system and partly due to the commercialization of the jet airplane. Excessive regulation of the railroads—in an effort to help farmers—also caused problems. In the 1960s and 1970s, many railroads went bankrupt. Finally, the government realized something had to be done and it passed the Staggers Act in 1980, deregulating the railroads:

The Staggers Act was a breath of fresh air. Railroads immediately started adjusting their rates to make economic sense. Unprofitable routes were dropped. With increased profits and with confidence in their future, railroads started spending more to modernize. New locomotives, freight cars, tracks, automated control systems, and computers reduced costs and increased reliability. The efficiencies allowed the railroads to reduce their rates and become more competitive with trucks and barges….

In the 1980s and 1990s, the railroad industry also enjoyed increased efficiencies through consolidating mergers. In the west, the Burlington Northern merged with the Santa Fe, and the Union Pacific merged with the Southern Pacific.

Union Pacific reduced costs during the 2001-2002 recession, but later this led to congestion on many of its routes and to the need to hire and train new employees once the economy had picked up again. Union Pacific experienced an earnings shortfall, leading the shares to decline to $14.86.

Wachenheim thought that Union Pacific’s problems were temporary, and that the company would earn about $1.55 in 2006. With a conservative multiple of 14 times earnings, the shares would be worth over $22 in 2006. Also, the company was paying a $0.30 annual dividend. So the total return over a two-year period from buying the shares at $14½ would be 55 percent.

Wachenheim also thought Union Pacific stock had good downside protection because the book value was $12 a share.

Furthermore, even if Union Pacific stock just matched the expected return from the S&P 500 Index of 9½ percent a year, that would still be much better than cash.

The fact that the S&P 500 Index increases about 9½ percent a year is an important reason why shorting stocks is generally a bad business. To do better than the market, the short seller has to find stocks that underperform the market by 19 percent a year. Also, short sellers have limited potential gains and unlimited potential losses. On the whole, shorting stocks is a terrible business and often even the smartest short sellers struggle.

Greenhaven sold its shares in Union Pacific at $31 in mid-2007, since other investors had recognized the stock’s value. Including dividends, Greenhaven earned close to a 24 percent annualized return.

Wachenheim asks why most stock analysts are not good investors. For one, most analysts specialize in one industry or in a few industries. Moreover, analysts tend to extrapolate known information, rather than define future scenarios and their probabilities of occurrence:

…in my opinion, most individuals, including securities analysts, feel more comfortable projecting current fundamentals into the future than projecting changes that will occur in the future. Current fundamentals are based on known information. Future fundamentals are based on unknowns. Predicting the future from unknowns requires the efforts of thinking, assigning probabilities, and sticking one’s neck out—all efforts that human beings too often prefer to avoid.

Also, I believe it is difficult for securities analysts to embrace companies and industries that currently are suffering from poor results and impaired reputations. Often, securities analysts want to see tangible proof of better results before recommending a stock. My philosophy is that life is not about waiting for the storm to pass. It is about dancing in the rain. One usually can read a weather map and reasonably project when a storm will pass. If one waits for the moment when the sun breaks out, there is a high probability others already will have reacted to the improved prospects and already will have driven up the price of the stock—and thus the opportunity to earn large profits will have been missed.

Wachenheim then quotes from a New York Times op-ed piece written on October 17, 2008, by Warren Buffett:

A simple rule dictates my buying: Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful. And most certainly, fear is now widespread, gripping even seasoned investors. To be sure, investors are right to be wary of highly leveraged entities or businesses in weak competitive positions. But fears regarding the long-term prosperity of the nation’s many sound companies make no sense. These businesses will indeed suffer earnings hiccups, as they always have. But most major companies will be setting new profit records 5, 10, and 20 years from now. Let me be clear on one point: I can’t predict the short-term movements of the stock market. I haven’t the faintest idea as to whether stocks will be higher or lower a month—or a year—from now. What is likely, however, is that the market will move higher, perhaps substantially so, well before either sentiment or the economy turns up. So if you wait for the robins, spring will be over.

AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL GROUP

(AIG Corporate, Photo by AIG, Wikimedia Commons)

Wachenheim is forthright in discussing Greenhaven’s investment in AIG, which turned out to be a huge mistake. In late 2005, Wachenheim estimated that the intrinsic value of AIG would be about $105 per share in 2008, nearly twice the current price of $55. Wachenheim also liked the first-class reputation of the company, so he bought shares.

In late April 2007, AIG’s shares had fallen materially below Greenhaven’s cost basis:

When shares of one of our holdings are weak, we usually revisit the company’s longer-term fundamentals. If the longer-term fundamentals have not changed, we normally will continue to hold the shares, if not purchase more. In the case of AIG, it appeared to us that the longer-term fundamentals remained intact.

When Lehman filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on September 15, 2008, all hell broke loose:

The decline in asset values caused financial institutions to mark down the carrying value of their assets, which, in turn, caused sharp reductions in their credit ratings. Sharp reductions in credit ratings required financial institutions to raise capital and, in the case of AIG, to post collateral on its derivative contracts. But the near freezing of the financial markets prevented the requisite raising of capital and cash and thus caused a further deterioration in creditworthiness, which further increased the need for new capital and cash, and so on… On Tuesday night, September 16, the U.S. government agreed to provide the requisite cash in return for a lion’s share of the ownership of AIG. As soon as I read the agreement, it was clear to me that we had a large permanent loss in our holdings of AIG.

Wachenheim defends the U.S. government bailouts. Much of the problem was liquidity, not solvency. Also, the bailouts helped restore confidence in the financial system.

Wachenheim asked himself if he would make the same decision today to invest in AIG:

My answer was ‘yes’—and my conclusion was that, in the investment business, relatively unpredictable outlier developments sometimes can quickly derail otherwise attractive investments. It comes with the territory. So while we work hard to reduce the risks of large permanent loss, we cannot completely eliminate large risks. However, we can draw a line on how much risk we are willing to accept—a line that provides sufficient apparent protection and yet prevents us from being so risk averse that we turn down too many attractive opportunities. One should not invest with the precept that the next 100-year storm is around the corner.

Wachenheim also points out that when Greenhaven learns of a flaw in its investment thesis, usually the firm is able to exit the position with only a modest loss. If you’re right 2/3 of the time and if you limit losses as much as possible, the results should be good over time.

LOWE’S

(Photo by Miosotis Jade, Wikimedia Commons)

In 2011, Wachenheim carefully analyzed the housing market and reached an interesting conclusion:

I was excited that we had a concept about a probable strong upturn in the housing market that was not shared by most others. I believed that the existing negativism about housing was due to the proclivity of human beings to uncritically project recent trends into the future and to overly dwell on existing problems. When analyzing companies and industries, I tend to be an optimist by nature and a pragmatist through effort. In terms of the proverbial glass of water, it is never half empty, but always half full—and, as a pragmatist, it is twice as large as it needs to be.

Next Wachenheim built a model to estimate normalized earnings for Lowe’s three years in the future (in 2014). He came up with normal earnings of $3 per share. He thought the appropriate price-to-earnings ratio was 16. So the stock would be worth $48 in 2014 versus its current price (in 2011) of $24. It looked like a bargain.

After gathering more information, Wachenheim revised his earnings model:

…I revise models frequently because my initial models rarely are close to being accurate. Usually, they are no better than directional. But they usually do lead me in the right direction, and, importantly, the process of constructing a model forces me to consider and weigh the central fundamentals of a company that will determine the company’s future value.

Wachenheim now thought that Lowe’s could earn close to $4.10 in 2015, which would make the shares worth even more than $48. In August 2013, the shares hit $45.

In late September 2013, after playing tennis, another money manager asked Wachenheim if he was worried that the stock market might decline sharply if the budget impasse in Congress led to a government shutdown:

I answered that I had no idea what the stock market would do in the near term. I virtually never do. I strongly believe in Warren Buffett’s dictum that he never has an opinion on the stock market because, if he did, it would not be any good, and it might interfere with opinions that are good. I have monitored the short-term market predictions of many intelligent and knowledgeable investors and have found that they were correct about half the time. Thus, one would do just as well by flipping a coin.

I feel the same way about predicting the short-term direction of the economy, interest rates, commodities, or currencies. There are too many variables that need to be identified and weighed.

As for Lowe’s, the stock hit $67.50 at the end of 2014, up 160 percent from what Greenhaven paid.

WHIRLPOOL CORPORATION

(Photo by Steven Pavlov, Wikimedia Commons)

Wachenheim does not believe in the Efficient Market Hypothesis:

It seems to me that the boom-bust of growth stocks in 1968-1974 and the subsequent boom-bust of Internet technology stocks in 1998-2002 serve to disprove the efficient market hypothesis, which states that it is impossible for an investor to beat the stock market because stocks always are efficiently priced based on all the relevant and known information on the fundamentals of the stocks. I believe that the efficient market hypothesis fails because it ignores human nature, particularly the nature of most individuals to be followers, not leaders. As followers, humans are prone to embrace that which already has been faring well and to shun that which recently has been faring poorly. Of course, the act of buying into what already is doing well and shunning what is doing poorly serves to perpetuate a trend. Other trend followers then uncritically join the trend, causing the trend to feed on itself and causing excesses.

Many investors focus on the shorter term, which generally harms their long-term performance:

…so many investors are too focused on short-term fundamentals and investment returns at the expense of longer-term fundamentals and returns. Hunter-gatherers needed to be greatly concerned about their immediate survival—about a pride of lions that might be lurking behind the next rock… They did not have the luxury of thinking about longer-term planning… Then and today, humans often flinch when they come upon a sudden apparent danger—and, by definition, a flinch is instinctive as opposed to cognitive. Thus, over years, the selection process resulted in a subconscious proclivity for humans to be more concerned about the short term than the longer term.

By far the best thing for long-term investors is to do is absolutely nothing. The investors who end up performing the best over the course of several decades are nearly always those investors who did virtually nothing. They almost never checked prices. They never reacted to bad news.

Regarding Whirlpool:

In the spring of 2011, Greenhaven studied Whirlpool’s fundamentals. We immediately were impressed by management’s ability and willingness to slash costs. In spite of a materially subnormal demand for appliances in 2010, the company was able to earn operating margins of 5.9 percent. Often, when a company is suffering from particularly adverse industry conditions, it is unable to earn any profit at all. But Whirlpool remained moderately profitable. If the company could earn 5.9 percent margins under adverse circumstances, what could the company earn once the U.S. housing market and the appliance market returned to normal?

Not surprisingly, Wall Street analysts were focused on the short term:

…A report by J. P. Morgan dated April 27, 2011, stated that Whirlpool’s current share price properly reflected the company’s increased costs for raw materials, the company’s inability to increase its prices, and the current soft demand for appliances…

The J. P. Morgan report might have been correct about the near-term outlook for Whirlpool and its shares. But Greenhaven invests with a two- to four-year time horizon and cares little about the near-term outlook for its holdings.

The bulk of Greenhaven’s returns has been generated by relatively few of its holdings:

If one in five of our holdings triples in value over a three-year period, then the other four holdings only have to achieve 12 percent average annual returns in order for our entire portfolio to achieve its stretch goal of 20 percent. For this reason, Greenhaven works extra hard trying to identify potential multibaggers. Whirlpool had the potential to be a multibagger because it was selling at a particularly low multiple of its potential earnings power. Of course, most of our potential multibaggers do not turn out to be multibaggers. But one cannot hit a multibagger unless one tries, and sometimes our holdings that initially appear to be less exciting eventually benefit from positive unforeseen events (handsome black swans) and unexpectedly turn out to be a complete winner. For this reason, we like to remain fully invested as long as our holdings remain reasonably priced and free from large risks of permanent loss.

BOEING

(Photo by José A. Montes, Wikimedia Commons)

Wachenheim likes to read about the history of each company that he studies.

On July 4, 1914, a flight took place in Seattle, Washington, that had a major effect on the history of aviation. On that day, a barnstormer named Terah Maroney was hired to perform a flying demonstration as part of Seattle’s Independence Day celebrations. After displaying aerobatics in his Curtis floatplane, Maroney landed and offered to give free rides to spectators. One spectator, William Edward Boeing, a wealthy owner of a lumber company, quickly accepted Maroney’s offer. Boeing was so exhilarated by the flight that he completely caught the aviation bug—a bug that was to be with him for the rest of his life.

Boeing launched Pacific Aero Products (renamed the Boeing Airplane Company in 1917). In late 1916, Boeing designed an improved floatplane, the Model C. The Model C was ready by April 1917, the same month the United States entered the war. Boeing thought the Navy might need training aircraft. The Navy bought two. They performed well, so the Navy ordered 50 more.

Boeing’s business naturally slowed down after the war. Boeing sold a couple of small floatplanes (B-1’s), then 13 more after Charles Lindberg’s 1927 transatlantic flight. Still, sales of commercial planes were virtually nonexistent until 1933, when the company started marketing its model 247.

The twin-engine 247 was revolutionary and generally is recognized as the world’s first modern airplane. It had a capacity to carry 10 passengers and a crew of 3. It had a cruising speed of 189 mph and could fly about 745 miles before needing to be refueled.

Boeing sold seventy-five 247’s before making the much larger 307 Stratoliner, which would have sold well were it not for the start of World War II.

Boeing helped the Allies defeat Germany. The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber and the B-29 Superfortress bomber became legendary. More than 12,500 B-17s and more than 3,500 B-29s were built (some by Boeing itself and some by other companies that had spare capacity).

Boeing prospered during the war, but business slowed down again after the war. In mid-1949, the de Havilland Aircraft Company started testing its Comet jetliner, the first use of a jet engine. The Comet started carrying passengers in 1952. In response, Boeing started developing its 707 jet. Commercial flights for the 707 began in 1958.

The 707 was a hit and soon became the leading commercial plane in the world.

Over the next 30 years, Boeing grew into a large and highly successful company. It introduced many models of popular commercial planes that covered a wide range of capacities, and it became a leader in the production of high-technology military aircraft and systems. Moreover, in 1996 and 1997, the company materially increased its size and capabilities by acquiring North American Aviation and McDonnell Douglas.

In late 2012, after several years of delays on its new, more fuel-efficient plane—the 787—Wall Street and the media were highly critical of Boeing. Wachenheim thought that the company could earn at least $7 per share in 2015. The stock in late 2012 was at $75, or 11 times the $7. Wachenheim believed that this was way too low for such a strong company.

Wachenheim estimated that two-thirds of Boeing’s business in 2015 would come from commercial aviation. He figured that this was an excellent business worth 20 times earnings (he used 19 times to be conservative). He reckoned that defense, one-third of Boeing’s business, was worth 15 times earnings. Therefore, Wachenheim used 17.7 as the multiple for the whole company, which meant that Boeing would be worth $145 by 2015.

Greenhaven established a position in Boeing at about $75 a share in late 2012 and early 2013. By the end of 2013, Boeing was at $136. Because Wall Street now had confidence that the 787 would be a commercial success and that Boeing’s earnings would rise, Wachenheim and his associates concluded that most of the company’s intermediate-term potential was now reflected in the stock price. So Greenhaven started selling its position.

SOUTHWEST AIRLINES

(Photo by Eddie Maloney, Wikimedia Commons)

The airline industry has had terrible fundamentals for a long time. But Wachenheim was able to be open-minded when, in August 2012, one of his fellow analysts suggested Southwest Airlines as a possible investment. Over the years, Southwest had developed a low-cost strategy that gave the company a clear competitive advantage.

Greenhaven determined that the stock of Southwest was undervalued, so they took a position.

The price of Southwest’s shares started appreciating sharply soon after we started establishing our position. Sometimes it takes years before one of our holdings starts to appreciate sharply—and sometimes we are lucky with our timing.

After the shares tripled, Greenhaven sold half its holdings since the expected return from that point forward was not great. Also, other investors now recognized the positive fundamentals Greenhaven had expected. Greenhaven sold the rest of its position as the shares continued to increase.

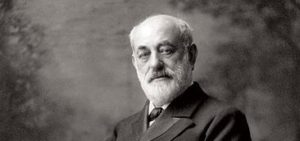

GOLDMAN SACHS

(Photo of Marcus Goldman, Wikimedia Commons)

Wachenheim echoes Warren Buffett when it comes to recognizing how much progress the United States has made:

My experience is that analysts and historians often dwell too much on a company’s recent problems and underplay its strengths, progress, and promise. An analogy might be the progress of the United States during the twentieth century. At the end of the century, U.S. citizens generally were far wealthier, healthier, safer, and better educated than at the start of the century. In fact, the century was one of extraordinary progress. Yet most history books tend to focus on the two tragic world wars, the highly unpopular Vietnam War, the Great Depression, the civil unrest during the Civil Rights movement, and the often poor leadership in Washington. The century was littered with severe problems and mistakes. If you only had read the newspapers and the history books, you likely would have concluded that the United States had suffered a century of relative and absolute decline. But the United States actually exited the century strong and prosperous. So did Goldman exit 2013 strong and prosperous.

In 2013, Wachenheim learned that Goldman had an opportunity to gain market share in investment banking because some competitors were scaling back in light of new regulations and higher capital requirements. Moreover, Goldman had recently completed a $1.9 billion cost reduction program. Compensation as a percentage of sales had declined significantly in the past few years.

Wachenheim discovered that Goldman is a technology company to a large extent, with a quarter of employees working in the technology division. Furthermore, the company had strong competitive positions in its businesses, and had sold or shut down sub-par business lines. Wachenheim checked his investment thesis with competitors and former employees. They confirmed that Goldman is a powerhouse.

Wachenheim points out that it’s crucial for investors to avoid confirmation bias:

I believe that it is important for investors to avoid seeking out information that reinforces their original analyses. Instead, investors must be prepared and willing to change their analyses and minds when presented with new developments that adversely alter the fundamentals of an industry or company. Good investors should have open minds and be flexible.

Wachenheim also writes that it’s very important not to invent a new thesis when the original thesis has been invalidated:

We have a straightforward approach. When we are wrong or when fundamentals turn against us, we readily admit we are wrong and we reverse our course. We do not seek new theories that will justify our original decision. We do not let errors fester and consume our attention. We sell and move on.

Wachenheim loves his job:

I am almost always happy when working as an investment manager. What a perfect job, spending my days studying the world, economies, industries, and companies; thinking creatively; interviewing CEOs of companies… How lucky I am. How very, very lucky.

BOOLE MICROCAP FUND

An equal weighted group of micro caps generally far outperforms an equal weighted (or cap-weighted) group of larger stocks over time. See the historical chart here: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

This outperformance increases significantly by focusing on cheap micro caps. Performance can be further boosted by isolating cheap microcap companies that show improving fundamentals. We rank microcap stocks based on these and similar criteria.

There are roughly 10-20 positions in the portfolio. The size of each position is determined by its rank. Typically the largest position is 15-20% (at cost), while the average position is 8-10% (at cost). Positions are held for 3 to 5 years unless a stock approaches intrinsic value sooner or an error has been discovered.

The mission of the Boole Fund is to outperform the S&P 500 Index by at least 5% per year (net of fees) over 5-year periods. We also aim to outpace the Russell Microcap Index by at least 2% per year (net). The Boole Fund has low fees.

If you are interested in finding out more, please e-mail me or leave a comment.

My e-mail: jb@boolefund.com

Disclosures: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this article may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of Boole Capital, LLC.