January 7, 2024

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in the Markets and in Life, is an excellent book. Below I summarize the main points.

Here’s the outline:

-

- Prologue

Part I: Solon’s Warning—Skewness, Asymmetry, and Induction

-

- One: If You’re So Rich, Why Aren’t You So Smart?

- Two: A Bizarre Accounting Method

- Three: A Mathematical Meditation on History

- Four: Randomness, Nonsense, and the Scientific Intellectual

- Five: Survival of the Least Fit—Can Evolution Be Fooled By Randomness?

- Six: Skewness and Asymmetry

- Seven: The Problem of Induction

Part II: Monkeys on Typewriters—Survivorship and Other Biases

-

- Eight: Too Many Millionaires Next Door

- Nine: It Is Easier to Buy and Sell Than Fry an Egg

- Ten: Loser Takes All—On the Nonlinearities of Life

- Eleven: Randomness and Our Brain—We Are Probability Blind

Part III: Wax in my Ears—Living With Randomitis

-

- Twelve: Gamblers’ Ticks and Pigeons in a Box

- Thirteen: Carneades Comes to Rome—On Probability and Skepticism

- Fourteen: Bacchus Abandons Antony

(Albrecht Durer’s Wheel of Fortune from Sebastien Brant’s Ship of Fools (1494) via Wikimedia Commons)

PROLOGUE

Taleb presents Table P.1 Table of Confusion, listing the central distinctions used in the book.

GENERAL

| Luck | Skills |

| Randomness | Determinism |

| Probability | Certainty |

| Belief, conjecture | Knowledge, certitude |

| Theory | Reality |

| Anecdote, coincidence | Causality, law |

| Forecast | Prophecy |

MARKET PERFORMANCE

| Lucky idiot | Skilled investor |

| Survivorship bias | Market outperformance |

FINANCE

| Volatility | Return (or drift) |

| Stochastic variable | Deterministic variable |

PHYSICS AND ENGINEERING

| Noise | Signal |

LITERARY CRITICISM

| None | Symbol |

PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

| Epistemic probability | Physical probability |

| Induction | Deduction |

| Synthetic proposition | Analytic proposition |

ONE: IF YOU’RE SO RICH, WHY AREN’T YOU SO SMART?

Taleb introduces an options trader Nero Tulip. He became convinced that being an options trader was even more interesting that being a pirate would be.

Nero is highly educated (like Taleb himself), with an undergraduate degree in ancient literature and mathematics from Cambridge University, a PhD. in philosophy from the University of Chicago, and a PhD. in mathematical statistics. His thesis for the PhD. in philosophy had to do with the methodology of statistical inference in its application to the social sciences. Taleb comments:

In fact, his thesis was indistinguishable from a thesis in mathematical statistics—it was just a bit more thoughtful (and twice as long).

Nero left philosophy because he became bored with academic debates, particularly over minor points. Nero wanted action.

(Photo by Neil Lockhart)

Nero became a proprietary trader. The firm provided the capital. As long as Nero generated good results, he was free to work whenever he wanted. Generally he was allowed to keep between 7% and 12% of his profits.

It is paradise for an intellectual like Nero who dislikes manual work and values unscheduled meditation.

Nero was an extremely conservative options trader. Over his first decade, he had almost no bad years and his after-tax income averaged $500,000. Due to his extreme risk aversion, Nero’s goal is not to maximize profits as much as it is to avoid having such a bad year that his “entertaining money machine called trading” would be taken away from him. In other words, Nero’s goal was to avoid blowing up, or having such a bad year that he would have to leave the business.

Nero likes taking small losses as long as his profits are large. Whereas most traders make money most of the time during a bull market and lose money during market panics or crashes, Nero would lose small amounts most of the time during a bull market and then make large profits during a market panic or crash.

Nero does not do as well as some other traders. One reason is that his extreme risk aversion leads him to invest his own money in treasury bonds. So he missed most of the bull market from 1982 to 2000.

Note: From a value investing point of view, Nero should at least have invested in undervalued stocks, since such a strategy will almost certainly do well after 10+ years. But Nero wasn’t trained in value investing, and he was acutely aware of what can happen during market panics or crashes.

Also Note: For a value investor, a market panic or crash is an opportunity to buy more stock at very cheap prices. Thus bear markets benefit the value investor who can add to his or her positions.

Nero and his wife live across the street from John the High-Yield Trader and his wife. John was doing much better than Nero. John’s strategy was to maximize profits for as long as the bull market lasted. Nero’s wife and even Nero himself would occasionally feel jealous when looking at the much larger house in which John and his wife lived. However, one day there was a market panic and John blew up, losing virtually everything including his house.

Taleb writes:

…Nero’s merriment did not come from the fact that John went back to his place in life, so much as it was from the fact that Nero’s methods, beliefs, and track record had suddenly gained in credibility. Nero would be able to raise public money on his track record precisely because such a thing could not possibly happen to him. A repetition of such an event would pay off massively for him. Part of Nero’s elation also came from the fact that he felt proud of his sticking to his strategy for so long, in spite of the pressure to be the alpha male. It was also because he would no longer question his trading style when others were getting rich because they misunderstood the structure of randomness and market cycles.

Taleb then comments that lucky fools never have the slightest suspicion that they are lucky fools. As long as they’re winning, they get puffed up from the release of the neurotransmitter serotonin into their systems. Taleb notes that our hormonal system can’t distinguish between winning based on luck and winning based on skill.

(A lucky seven. Photo by Eagleflying)

Furthermore, when serotonin is released into our system based on some success, we act like we deserve the success, regardless of whether it was based on luck or skill. Our new behavior will often lead to a virtuous cycle during which, if we continue to win, we will rise in the pecking order. Similarly, when we lose, whether that loss is due to bad luck or poor skill, our resulting behavior will often lead to a vicious cycle during which, if we continue to lose, we will fall in the pecking order. Taleb points out that these virtuous and vicious cycles are exactly what happens with monkeys who have been injected with serotonin.

Taleb adds that you can always tell whether some trader has had a winning day or a losing day. You just have to observe his or her gesture or gait. It’s easy to tell whether the trader is full of serotonin or not.

TWO: A BIZARRE ACCOUNTING METHOD

Taleb introduces the concept of alternative histories. This concept applies to many areas of human life, including many different professions (war, politics, medicine, investments). The main idea is that you cannot judge the quality of a decision based only on its outcome. Rather, the quality of a decision can only be judged by considering all possible scenarios (outcomes) and their associated probabilities.

Once again, our brains deceive us unless we develop the habit of thinking probabilistically, in terms of alternative histories. Without this habit, if a decision is successful, we get puffed up with serotonin and believe that the successful outcome is based on our skill. By nature, we cannot account for luck or randomness.

Taleb offers Russian roulette as an analogy. If you are offered $10 million to play Russian roulette, and if you play and you survive, then you were lucky even though you will get puffed up with serotonin.

Taleb argues that many (if not most) business successes have a large component of luck or randomness. Again, though, successful businesspeople in general will be puffed up with serotonin and they will attribute their success primarily to skill. Taleb:

…the public observes the external signs of wealth without even having a glimpse at the source (we call such source the generator).

Now, if the lucky Russian roulette player continues to play the game, eventually the bad histories will catch up with him or her. Here’s an important point: If you start out with thousands of people playing Russian roulette, then after the first round roughly 83.3% will be successful. After the second round, roughly 83.3% of the survivors of round one will be successful. After the third round, roughly 83.3% of the survivors of round two will be successful. And on it goes… After twenty rounds, there will be a small handful of extremely successful and wealthy Russian roulette players. However, these cases of extreme success are due entirely to luck.

In the business world, of course, there are many cases where skill plays a large role. The point is that our brains by nature are unable to see when luck has played a role in some successful outcome. And luck almost always plays an important role in most areas of life.

Taleb points out that there are some areas where success is due mostly to skill and not luck. Taleb likes to give the example of dentistry. The success of a dentist will typically be due mostly to skill.

Taleb attributes some of his attitude towards risk to the fact that at one point he had a boss who forced him to consider every possible scenario, no matter how remote.

Interestingly, Taleb understands Homer’s The Iliad as presenting the following idea: heroes are heroes based on heroic behavior and not based on whether they won or lost. Homer seems to have understood the role of chance (luck).

THREE: A MATHEMATICAL MEDITATION ON HISTORY

A Monte Carlo generator creates many alternative random sample paths. Note that a sample path can be deterministic, but our concern here is with random sample paths. Also note that some random sample paths can have higher probabilities than other random sample paths. Each sample path represents just one sequence of events out of many possible sequences, ergo the word “sample”.

Taleb offers a few examples of random sample paths. Consider the price of your favorite technology stock, he says. It may start at $100, hit $220 along the way, and end up at $20. Or it may start at $100 and reach $145, but only after touching $10. Another example might be your wealth during at a night at the casino. Say you begin with $1,000 in your pocket. One possibility is that you end up with $2,200, while another possibility is that you end up with only $20.

Taleb says:

My Monta Carlo engine took me on a few interesting adventures. While my colleagues were immersed in news stories, central bank announcements, earnings reports, economic forecasts, sports results and, not least, office politics, I started toying with it in fields bordering my home base of financial probability. A natural field of expansion for the amateur is evolutionary biology… I started simulating populations of fast mutating animals called Zorglubs under climactic changes and witnessing the most unexpected of conclusions… My aim, as a pure amateur fleeing the boredom of business life, was merely to develop intuitions for these events… I also toyed with molecular biology, generating randomly occurring cancer cells and witnessing some surprising aspects to their evolution.

Taleb continues:

Naturally the analogue to fabricating populations of Zorglubs was to simulate a population of “idiotic bull”, “impetuous bear”, and “cautious” traders under different market regimes, say booms and busts, and to examine their short-term and long-term survival… My models showed almost nobody to really ultimately make money; bears dropped out like flies in the rally and bulls got ultimately slaughtered, as paper profits vanished when the music stopped. But there was one exception; some of those who traded options (I called them option buyers) had remarkable staying power and I wanted to be one of those. How? Because they could buy insurance against the blowup; they could get anxiety-free sleep at night, thanks to the knowledge that if their careers were threatened, it would not be owing to the outcome of a single day.

Note from a value investing point of view

A value investor seeks to pay low prices for stock in individual businesses. Stock prices can jump around in the short term. But over time, if the business you invest in succeeds, then the stock will follow, assuming you bought the stock at relatively low prices. Again, if there’s a bear market or a market crash, and if the stock prices of the businesses in which you’ve invested decline, then that presents a wonderful opportunity to buy more stock at attractively low prices. Over time, the U.S. and global economy will grow, regardless of the occasional market panic or crash. Because of this growth, one of the lowest risk ways to build wealth is to invest in businesses, either on an individual basis if you’re a value investor or via index funds.

Taleb’s methods of trying to make money during a market panic or crash will almost certainly do less well over the long term than simple index funds.

Taleb makes a further point: The vast majority of people learn only from their own mistakes, and rarely from the mistakes of others. Children only learn that the stove is hot by getting burned. Adults are largely the same way: We only learn from our own mistakes. Rarely do we learn from the mistakes of others. And rarely do we heed the warnings of others. Taleb:

All of my colleagues whom I have known to denigrate history blew up spectacularly—and I have yet to encounter some such person who has not blown up.

Keep in mind that Taleb is talking about traders here. For a regular investor who dollar cost averages into index funds and/or who uses value investing, Taleb’s warning does not apply. As a long-term investor in index funds and/or in value investing techniques, you do have to be ready for a 50% decline at some point. But if you buy more after such a decline, your long-term results will actually be helped, not hurt, by a 50% decline.

Taleb points out that aged traders and investors are likely better to use as role models precisely because they have been exposed to markets longer. Taleb:

I toyed with Monte Carlo simulations of heterogeneous populations of traders under a variety of regimes (closely resembling historical ones), and found a significant advantage in selecting aged traders, using, as a selection criterion their cumulative years of experience rather than their absolute success (conditional on their having survived without blowing up).

Taleb also observes that there is a similar phenomenon in mate selection. All else equal, women prefer to mate with healthy older men over healthy younger ones. Healthy older men, by having survived longer, show some evidence of better genes.

FOUR: RANDOMNESS, NONSENSE, AND THE SCIENTIFIC INTELLECTUAL

Using a random generator of words, it’s possible to create rhetoric, but it’s not possible to generate genuine scientific knowledge.

FIVE: SURVIVAL OF THE LEAST FIT—CAN EVOLUTION BE FOOLED BY RANDOMNESS?

Taleb writes about Carlos “the emerging markets wizard.” After excelling as an undergraduate, Carlos went for a PhD. in economics from Harvard. Unable to find a decent thesis topic for his dissertation, he settled for a master’s degree and a career on Wall Street.

Carlos did well investing in emerging markets bonds. One important reason for his success, beyond the fact that he bought emerging markets bonds that later went up in value, was that he bought the dips. Whenever there was a momentary panic and emerging markets bonds dropped in value, Carlos bought more. This dip buying improved his performance. Taleb:

It was the summer of 1998 that undid Carlos—that last dip did not translate into a rally. His track record today includes just one bad quarter—but bad it was. He had earned close to $80 million cumulatively in his previous years. He lost $300 million in just one summer.

When the market first started dipping, Carlos learned that a New Jersey hedge fund was liquidating, including its position in Russian bonds. So when Russian bonds dropped to $52, Carlos was buying. To those who questioned his buying, he yelled: “Read my lips: it’s li-qui-da-tion!”

Taleb continues:

By the end of June, his trading revenues for 1998 had dropped from up $60 million to up $20 million. That made him angry. But he calculated that should the market rise back to the pre-New Jersey selloff, then he would be up $100 million. That was unavoidable, he asserted. These bonds, he said, would never, ever trade below $48. He was risking so little, to possibly make so much.

Then came July. The market dropped a bit more. The benchmark Russian bond was now $43. His positions were under water, but he increased his stakes. By now he was down $30 million for the year. His bosses were starting to become nervous, but he kept telling them that, after all, Russia would not go under. He repeated the cliche that it was too big to fail. He estimated that bailing them out would cost so little and would benefit the world economy so much that it did not make sense to liquidate his inventory now.

Carlos asserted that the Russian bonds were trading near default value. If Russia were to default, then Russian bonds would stay at the same prices they were at currently. Carlos took the further step of investing half of his net worth, then $5,000,000, into Russian bonds.

Russian bond prices then dropped into the 30s, and then into the 20s. Since Carlos thought the bonds could not be less than the default values he had calculated, and were probably worth much more, he was not alarmed. He maintained that anyone who invested in Russian bonds at these levels would realize wonderful returns. He claimed that stop losses “are for schmucks! I am not going to buy high and sell low!” He pointed out that in October 1997 they were way down, but that buying the dip ended up yielding excellent profits for 1997. Furthermore, Carlos pointed out that other banks were showing even larger losses on their Russian bond positions. Taleb:

Towards the end of August, the bellwether Russian Principal Bonds were trading below $10. Carlos’s net worth was reduced by almost half. He was dismissed. So was his boss, the head of trading. The president of the bank was demoted to a “newly created position”. Board members could not understand why the bank had so much exposure to a government that was not paying its own employees—which, disturbingly, included armed soldiers. This was one of the small points that emerging market economists around the globe, from talking to each other so much, forgot to take into account.

Taleb adds:

Louie, a veteran trader on the neighboring desk who suffered much humiliation by these rich emerging market traders, was there, vindicated. Louie was then a 52-year-old Brooklyn-born-and-raised trader who over three decades survived every single conceivable market cycle.

Taleb concludes that Carlos is a gentleman, but a bad trader:

He has all of the traits of a thoughtful gentleman, and would be an ideal son-in-law. But he has most of the attributes of the bad trader. And, at any point in time, the richest traders are often the worst traders. This, I will call the cross-sectional problem: at a given time in the market, the most profitable traders are likely to be those that are best fit to the latest cycle.

Taleb discusses John the high-yield trader, who was mentioned near the beginning of the book, as another bad trader. What traits do bad traders, who may be lucky idiots for awhile, share? Taleb:

-

- An overestimation of the accuracy of their beliefs in some measure, either economic (Carlos) or statistical (John). They don’t consider that what they view as economic or statistical truth may have been fit to past events and may no longer be true.

- A tendency to get married to positions.

- The tendency to change their story.

- No precise game plan ahead of time as to what to do in the event of losses.

- Absence of critical thinking expressed in absence of revision of their stance with “stop losses”.

- Denial.

SIX: SKEWNESS AND ASYMMETRY

Taleb presents the following Table:

| Event | Probability | Outcome | Expectation |

| A | 999/1000 | $1 | $.999 |

| B | 1/1000 | -$10,000 | -$10.00 |

| Total | -$9.001 |

The point is that the frequency of losing cannot be considered apart from the magnitude of the outcome. If you play the game, you’re extremely likely to make $1. But it’s not a good idea to play. If you play this game millions of times, you’re virtually guaranteed to lose money.

Taleb comments that even professional investors misunderstand this bet:

How could people miss such a point? Why do they confuse probability and expectation, that is, probability and probability times the payoff? Mainly because much of people’s schooling comes from examples in symmetric environments, like a coin-toss, where such a difference does not matter. In fact the so-called “Bell Curve” that seems to have found universal use in society is entirely symmetric.

(Coin toss. Photo by Christian Delbert)

Taleb gives an example where he is shorting the S&P 500 Index. He thought the market had a 70% chance of going up and a 30% chance of going down. But he thought that if the market went down, it could go down a lot. Therefore, it was profitable over time (by repeating the bet) to be short the S&P 500.

Note: From a value investing point of view, no one can predict what the market will do. But you can predict what some individual businesses are likely to do. The key is to invest in businesses when the price (stock) is low.

Rare Events

Taleb explains his trading strategy:

The best description of my lifelong business in the market is “skewed bets”, that is, I try to benefit from rare events, events that do not tend to repeat themselves frequently, but, accordingly, present a large payoff when they occur. I try to make money infrequently, as infrequently as possible, simply because I believe that rare events are not fairly valued, and that the rarer the event, the more undervalued it will be in price.

Taleb gives an example where his strategy paid off:

One such rare event is the stock market crash of 1987, which made me as a trader and allowed me the luxury of becoming involved in all manner of scholarship.

Taleb notes that in most areas of science, it is common practice to discard outliers when computing the average. For instance, a professor calculating the average grade in his or her class might discard the highest and the lowest values. In finance, however, it is often wrong to discard the extreme outcomes because, as Taleb has shown, the magnitude of an extreme outcome can matter.

Taleb advises studying market history. But then again, you have to be careful, as Taleb explains:

Sometimes market data becomes a simple trap; it shows you the opposite of its nature, simply to get you to invest in the security or mismanage your risks. Currencies that exhibit the largest historical stability, for example, are the most prone to crashes…

Taleb notes the following:

In other words history teaches us that things that never happened before do happen.

History does not always repeat. Sometimes things change. For instance, today the U.S. stock market seems high. The S&P 500 Index is over 3,000. Based on history, one might expect a bear market and/or a recession. There hasn’t been a recession in the U.S. since 2009.

However, with interest rates low, and with the profit margins on many technology companies high, it’s possible that stocks will not decline much, even if there’s a recession. It’s also possible that any recession could be delayed, partly because the Fed and other central banks remain very accommodative. It’s possible that the business cycle itself may be less volatile because the fiscal and monetary authorities have gotten better at delaying recessions or at making recessions shallower than before.

Ironically, to the extent that Taleb seeks to profit from a market panic or crash, for the reasons just mentioned, Taleb’s strategy may not work as well going forward.

Taleb introduces the problem of stationarity. To illustrate the problem, think of an urn with red balls and black balls in it. Taleb:

Think of an urn that is hollow at the bottom. As I am sampling from it, and without my being aware of it, some mischievous child is adding balls of one color or another. My inference thus becomes insignificant. I may infer that the red balls represent 50% of the urn while the mischievous child, hearing me, would swiftly replace all the red balls with black ones. This makes much of our knowledge derived through statistics quite shaky.

The very same effect takes place in the market. We take past history as a single homogeneous sample and believe that we have considerably increased our knowledge of the future from the observation of the sample of the past. What if vicious children were changing the composition of the urn? In other words, what if things have changed?

Taleb notes that there are many techniques that use past history in order to measure risks going forward. But to the extent that past data are not stationary, depending upon these risk measurement techniques can be a serious mistake. All of this leads to a more fundamental issue: the problem of induction.

SEVEN: THE PROBLEM OF INDUCTION

Taleb quotes the Scottish philosopher David Hume:

No amount of observations of white swans can allow the inference that all swans are white, but the observation of a single black swan is sufficient to refute that conclusion.

(Black swan. Photo by Damithri)

Taleb came to believe that Sir Karl Popper had an important answer to the problem of induction. According to Popper, there are only two types of scientific theories:

-

- Theories that are known to be wrong, as they were tested and adequately rejected (i.e., falsified).

- Theories that have not yet been known to be wrong, not falsified yet, but are exposed to be proved wrong.

It also follows that we should not always rely on statistics. Taleb:

More practically to me, Popper had many problems with statistics and statisticians. He refused to blindly accept the notion that knowledge can always increase with incremental information—which is the foundation for statistical inference. It may in some instances, but we do not know which ones. Many insightful people, such as John Maynard Keynes, independently reached the same conclusions. Sir Karl’s detractors believe that favorably repeating the same experiment again and again should lead to an increased comfort with the notion that “it works”.

Taleb explains the concept of an open society:

Popper’s falsificationism is intimately connected to the notion of an open society. An open society is one in which no permanent truth is held to exist; this would allow counterideas to emerge.

For Taleb, a successful trader or investor must have an open mind in which no permanent truth is held to exist.

Taleb concludes the chapter by applying the logic of Pascal’s wager to trading and investing:

…I will use statistics and inductive methods to make aggressive bets, but I will not use them to manage my risks and exposure. Surprisingly, all the surviving traders I know seem to have done the same. They trade on ideas based on some observation (that includes past history) but, like the Popperian scientists, they make sure that the costs of being wrong are limited (and their probability is not derived from past data). Unlike Carlos and John, they know before getting involved in the trading strategy which events would prove their conjecture wrong and allow for it (recall the Carlos and John used past history both to make their bets and measure their risk).

PART II: MONKEYS ON TYPEWRITERS—SURVIVORSHIP AND OTHER BIASES

If you put an infinite number of monkeys in front of typewriters, it is certain that one of them will type an exact version of Homer’s The Iliad. Taleb asks:

Now that we have found that hero among monkeys, would any reader invest his life’s savings on a bet that the monkey would write The Odyssey next?

EIGHT: TOO MANY MILLIONAIRES NEXT DOOR

Taleb begins the chapter by describing a lawyer named Marc. Marc makes $500,000 a year. He attended Harvard as an undergraduate and then Yale Law School. The problem is that some of Marc’s neighbors are much wealthier. Taleb discusses Marc’s wife, Janet:

Every month or so, Janet has a crisis… Why isn’t her husband so successful? Isn’t he smart and hard working? Didn’t he get close to 1600 on the SAT? Why is Ronald Something whose wife never even nods to Janet worth hundred of millions when her husband went to Harvard and Yale and has such a high I.Q., and has hardly any substantial savings?

Note: Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger have long made the point that envy is a massively stupid sin because, unlike other sins (e.g., gluttony), you can’t have any fun with it. Granted, envy is a very human emotion. But we can and must train ourselves not to fall into it.

Daniel Kahneman and others have demonstrated that the average person would rather make $70,000 as long as his neighbor makes $60,000 than make $80,000 if his neighbor makes $90,000. How stupid to compare ourselves to people who happen to be doing better! There will always be someone doing better.

Taleb mentions the book, The Millionaire Next Door. One idea from the book is that the wealthy often do not look wealthy because they’re focused on saving and investing, rather than on spending. However, Taleb finds two problems with the book. First, the book does not adjust for survivorship bias. In other words, for at least some of the wealthy, there is some luck involved. Second, there’s the problem of induction. If you measure someone’s wealth in the year 2000 (Taleb was writing in 2001), at the end of one of the biggest bull markets in modern history (from 1982 to 2000), then in many cases a large degree of that wealth came as a result of the prolonged bull market. By contrast, if you measure people’s wealth in 1982, there would be fewer people who are millionaires, even after adjusting for inflation.

NINE: IT IS EASIER TO BUY AND SELL THAN FRY AN EGG

Taleb writes about going to the dentist and being confident that his dentist knows something about teeth. Later, Taleb goes to Carnegie Hall. Before the pianist begins her performance, Taleb has zero doubt that she knows how to play the piano and is not about to produce cacophony. Later still, Taleb is in London and ends up looking at some of his favorite marble statues. Once again, he knows they weren’t produced by luck.

However, in many areas of business and even more so when it comes to investing, luck does tend to play a large role. Taleb is supposed to meet with a fund manager who has a good track record and who is looking for investors. Taleb comments that buying and selling, which is what the fund manager does, is easier than frying an egg. The problem is that luck plays such a large role in almost any good investment track record.

In order to study the role luck plays for investors, Taleb suggests a hypothetical game. There are 10,000 investors at the beginning. In the first round, a fair coin is tossed for each investor. Heads, and the investor makes $10,000, tails, and the investor loses $10,000. (Any investor who has a losing year is not allowed to continue to play the game.) After the first round, there will be about 5,000 successful investors. In the second round, a fair coin is again tossed. After the second round, there will be 2,500 successful investors. Another round, and 1,250 will remain. A fourth round, and 625 successful investors will remain. A fifth round, and 313 successful investors will remain. Based on luck alone, after five years there will be approximately 313 investors with winning track records. No doubt these 313 winners will be puffed up with serotonin.

Taleb then observes that you can play the same hypothetical game with bad investors. You assume each year that there’s a 45% chance of winning and a 55% chance of losing. After one year, 4,500 successful (but bad) investors will remain. After two years, 2,025. After three years, 911. After four years, 410. After five years, there will be 184 bad investors who have successful track records.

Taleb makes two counterintuitive points:

-

- First, even starting with only bad investors, you will end up with a small number of great track records.

- Second, how many great track records you end up with depends more on the size of the initial sample—how many investors you started with—than it does on the individual odds per investor. Applied to the real world, this means that if there are more investors who start in 1997 than in 1993, then you will see a greater number of successful track records in 2002 than you will see in 1998.

Taleb concludes:

Recall that the survivorship bias depends on the size of the initial population. The information that a person made money in the past, just by itself, is neither meaningful nor relevant. We need to know that size of the population from which he came. In other words, without knowing how many managers out there have tried and failed, we will not be able to assess the validity of the track record. If the initial population includes ten managers, then I would give the performer half my savings without a blink. If the initial population is composed of 10,000 managers, I would ignore the results.

The mysterious letter

Taleb tells a story. You get a letter on Jan. 2 informing you that the market will go up during the month. It does. Then you get a letter on Feb. 1 saying the market will go down during the month. It does. You get another letter on Mar. 1. Same story. Again for April and for May. You’ve now gotten five letters in a row predicting what the market would do during the ensuing month, and all five letters were correct. Next you are asked to invest in a special fund. The fund blows up. What happened?

The trick is as follows. The con operator gets 10,000 random names. On Jan. 2, he mails 5,000 letters predicting that the market will go up and 5,000 letters predicting that the market will go down. The next month, he focuses only on the 5,000 names who were just mailed a correct prediction. He sends 2,500 letters predicting that the market will go up and 2,500 letters predicting that the market will go down. Of course, next he focuses on the 2,500 letters which gave correct predictions. He mails 1,250 letters predicting a market rise and 1,250 predicting a market fall. After five months of this, there will be approximately 200 people who received five straight correct predictions.

Taleb suggests the birthday paradox as an intuitive way to explain the data mining problem. If you encounter a random person, there is a one in 365.25 chance that you have the same birthday. But if you have 23 random people in a room, the odds are close to 50 percent that you can find two people who share a birthday.

Similarly, what are the odds that you’ll run into someone you know in a totally random place? The odds are quite high because you are testing for any encounter, with any person you know, in any place you will visit.

Taleb continues:

What is your probability of winning the New Jersey lottery twice? One in 17 trillion. Yet it happened to Evelyn Adams, whom the reader might guess should feel particularly chosen by destiny. Using the method we developed above, Harvard’s Percy Diaconis and Frederick Mosteller estimated at 30 to 1 the probability the someone, somewhere, in a totally unspecified way, gets so lucky!

What is data snooping? It’s looking at historical data to determine the hypothetical performance of a large number of trading rules. The more trading rules you examine, the more likely you are to find trading rules that would have worked in the past and that one might expect to work in the future. However, many such trading rules would have worked in the past based on luck alone.

Taleb next writes about companies that increase their earnings. The same logic can be applied. If you start out with 10,000 companies, then by luck 5,000 will increase their profits after the first year. After three years, there will be 1,250 “stars” that increased their profits for three years in a row. Analysts will rate these companies a “strong buy”. The point is not that profit increases are entirely due to luck. The poin, rather, is that luck often plays a significant role in business results, usually far more than is commonly supposed.

TEN: LOSER TAKES ALL—ONE THE NONLINEARITIES OF LIFE

Taleb writes:

This chapter is about how a small advantage in life can translate into a highly disproportionate payoff, or, more viciously, how no advantage at all, but a very, very small help from randomness, can lead to a bonanza.

Nonlinearity is when a small input can lead to a disproportionate response. Consider a sandpile. You can add many grains of sand with nothing happening. Then suddenly one grain of sand causes an avalanche.

(Photo by Maocheng)

Taleb mentions actors auditioning for parts. A handful of actors get certain parts, and a few of them become famous. The most famous actors are not always the best actors (although they often are). Rather, there could have been random (lucky) reasons why a handful of actors got certain parts and why a few of them became famous.

The QWERTY keyboard is not optimal. But so many people were trained on it, and so many QWERTY keyboards were manufactured, that it has come to dominate. This is called a path dependent outcome. Taleb comments:

Such ideas go against classical economic models, in which results either come from a precise reason (there is no account for uncertainty) or the good guy wins (the good guy is the one who is more skilled and has some technical superiority)… Brian Arthur, an economist concerned with nonlinearities at the Santa Fe Institute, wrote that chance events coupled with positive feedback rather than technological superiority will determine economic superiority—not some abstrusely defined edge in a given area of expertise. While early economic models excluded randomness, Arthur explained how “unexpected orders, chance meetings with lawyers, managerial whims… would help determine which ones achieved early sales and, over time, which firms dominated”.

Taleb continues by noting that Arthur suggests a mathematical model called the Polya process:

The Polya process can be presented as follows: assume an urn initially containing equal quantities of black and red balls. You are to guess each time which color you will pull out before you make the draw. Here the game is rigged. Unlike a conventional urn, the probability of guessing correctly depends on past success, as you get better or worse at guessing depending on past performance. Thus the probability of winning increases after past wins, that of losing increases after past losses. Simulating such a process, one can see a huge variance of outcomes, with astonishing successes and a large number of failures (what we called skewness).

ELEVEN: RANDOMNESS AND OUR BRAIN—WE ARE PROBABILITY BLIND

Our genes have not yet evolved to the point where our brains can naturally compute probabilities. Computing probabilities is not something we even needed to do until very recently.

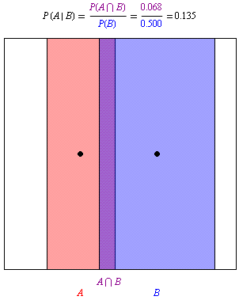

Here’s a diagram of how to compute the probability of A, conditional on B having happened:

(Diagram by Oleg Alexandrov, via Wikimedia Commons)

Taleb:

We are capable of sending a spacecraft to Mars, but we are incapable of having criminal trials managed by the basic laws of probability—yet evidence is clearly a probabilistic notion…

People who are as close to being criminal as probability laws can allow us to infer (that is with a confidence that exceeds the shadow of a doubt) are walking free because of our misunderstanding of basic concepts of the odds… I was in a dealing room with a TV set turned on when I saw one of the lawyers arguing that there were at least four people in Los Angeles capable of carrying O.J. Simpson’s DNA characteristics (thus ignoring the joint set of events…). I then switched off the television set in disgust, causing an uproar among the traders. I was under the impression until then that sophistry had been eliminated from legal cases thanks to the high standards of republican Rome. Worse, one Harvard lawyer used the specious argument that only 10% of men who brutalize their wives go on to murder them, which is a probability unconditional on the murder… Isn’t the law devoted to the truth? The correct way to look at it is to determine the percentage of murder cases where women were killed by their husband and had previously been battered by him (that is, 50%)—for we are dealing with what is called conditional probabilities; the probability that O.J. killed his wife conditional on the information of her having been killed, rather than the unconditional probability of O.J. killing his wife. How can we expect the untrained person to understand randomness when a Harvard professor who deals and teaches the concept of probabilistic evidence can make such an incorrect statement?

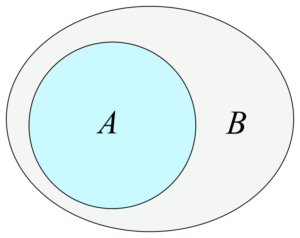

Speaking of people misunderstanding probabilities, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have asked groups to answer the following question:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

-

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

The majority of people believe that 2. is more probable the 1. But that’s an obvious fallacy. Bank tellers who are also feminists is a subset of all bank tellers, therefore 1. is more probable than 2. To see why, consider the following diagram:

(By svjo, via Wikimedia Commons)

B represents ALL bank tellers. Out of ALL bank tellers, some are feminists and some are not. Those bank tellers that are also feminists is represented by A.

Here’s a probability question that was presented to doctors:

A test of a disease presents a rate of 5% false positives. The disease strikes 1/1,000 of the population. People are tested at random, regardless of whether they are suspected of having the disease. A patient’s test is positive. What is the probability of the patient being stricken with the disease?

Many doctors answer 95%, which is wildly incorrect. The answer is close to 2%. Less than one in five doctors get the question right.

To see the right answer, assume that there are no false negatives. Out of 1,000 patients, one will have the disease. Consider the remaining 999. 50 of them will test positive. The probability of being afflicted with the disease for someone selected at random who tested positive is the following ratio:

Number of afflicted persons / Number of true and false positives

So the answer is 1/51, about 2%.

Another example where people misunderstand probabilities is when it comes to valuing options. (Recall that Taleb is an options trader.) Taleb gives an example. Say that the stock price is $100 today. You can buy a call option for $1 that gives you the right to buy the stock at $110 any time during the next month. Note that the option is out-of-the-money because you would not gain if you exercised your right to buy now, given that the stock is $100, below the exercise price of $110.

Now, what is the expected value of the option? About 90 percent of out-of-the-money options expire worthless, that is, they end up being worth $0. But the expected value is not $0 because there is a 10 percent chance that the option could be worth, say $10, because the stock went to $120. So even though it is 90 percent likely that the option will end up being worth $0, the expected value is not $0. The actual expected value in this example is:

(90% x $0) + (10% x $10) = $0 + $1 = $1

The expected value of the option is $1, which means you would have paid a fair price if you had bought it for $1. Taleb notes:

I discovered very few people who accepted losing $1 for most expirations and making $10 once in a while, even if the game were fair (i.e., they made the $10 more than 10% of the time).

“Fair” is not the right term here. If you make $10 more than 10% of the time, then the game has a positive expected value. That means if you play the game repeatedly, then eventually over time you will make money. Taleb’s point is that even if the game has a positive expected value, very few people would like to play it because on your way to making money, you have to accept small losses most of the time.

Taleb distinguishes between premium sellers, who sell options, and premium buyers, who buy options. Following the same logic as above, premium sellers make small amounts of money roughly 90% of the time, and then take a big loss roughly 10% of the time. Premium buyers lose small amounts about 90% of the time, and then have a big gain about 10% of the time.

Is it better to be an option seller or an option buyer? It depends on whether you can find favorable odds. It also depends on your temperament. Most people do not like taking small losses most of the time. Taleb:

Alas, most option traders I encountered in my career are premium sellers—when they blow up it is generally other people’s money.

PART III: WAX IN MY EARS—LIVING WITH RANDOMITIS

Taleb writes that when Odysseus and his crew encountered the sirens, Odysseus had his crew put wax in their ears. He also instructed his crew to tie him to the mast. With these steps, Odysseus and crew managed to survive the sirens’ songs. Taleb notes that he would be not Odysseus, but one of the sailors who needed to have wax in his ears.

(Odysseus and crew at the sirens. Illustration by Mr1805)

Taleb admits that he is dominated by his emotions:

The epiphany I had in my career in randomness came when I understood that I was not intelligent enough, nor strong enough, to even try to fight my emotions. Besides, I believe that I need my emotions to formulate my ideas and get the energy to execute them.

I am just intelligent enough to understand that I have a predisposition to be fooled by randomness—and to accept the fact that I am rather emotional. I am dominated by my emotions—but as an aesthete, I am happy about that fact. I am just like every single character whom I ridiculed in this book… The difference between myself and those I ridicule is that I try to be aware of it. No matter how long I study and try to understand probability, my emotions will respond to a different set of calculations, those that my unintelligent genes want me to handle.

Taleb says he has developed tricks in order to handle his emotions. For instance, if he has financial news playing on the television, he keeps the volume off. Without volume, a babbling person looks ridiculous. This trick helps Taleb stay free of news that is not rationally presented.

TWELVE: GAMBLERS’ TICKS AND PIGEONS IN A BOX

Early in his career as a trader, Taleb says he had a particularly profitable day. It just so happens that the morning of this day, Taleb’s cab driver dropped him off in the wrong location. Taleb admits that he was superstitious. So the next day, he not only wore the same tie, but he had his cab driver drop him off in the same wrong location.

(Skinner boxes. Photo by Luis Dantas, via Wikimedia Commons)

B.F. Skinner did an experiment with famished pigeons. There was a mechanism that would deliver food to the box in which the hungry pigeon was kept. But Skinner programmed the mechanism to deliver the food randomly. Taleb:

He saw quite astonishing behavior on the part of the birds; they developed an extremely sophisticated rain-dance type of behavior in response to their ingrained statistical machinery. One bird swung its head rhythmically against a specific corner of the box, others spun their heads anti-clockwise; literally all of the birds developed a specific ritual that progressively became hard-wired into their mind as linked to their feeding.

Taleb observes that whenever we experience two events, A and B, our mind automatically looks for a causal link even though there often is none. Note: Even if B always follows A, that doesn’t prove a causal link, as Hume pointed out.

Taleb again admits that after he has calculated the probabilities in some situation, he finds it hard to modify his own conduct accordingly. He gives an example of trading. Taleb says if he is up $100,000, there is a 98% chance that it’s just noise. But if he is up $1,000,000, there is a 1% chance that it’s noise and a 99% chance that his strategy is profitable. Taleb:

A rational person would act accordingly in the selection of strategies, and set his emotions in accordance with his results. Yet I have experienced leaps of joy over results that I knew were mere noise, and bouts of unhappiness over results that did not carry the slightest degree of statistical significance. I cannot help it…

Taleb uses another trick to deal with this. He denies himself access to his performance report unless it hits a predetermined threshold.

THIRTEEN: CARNEADES COMES TO ROME—ON PROBABILITY AND SKEPTICISM

Taleb writes:

Carneades was not merely a skeptic; he was a dialectician, someone who never committed himself to any of the premises from which he argued, or to any of the conclusions he drew from them. He stood all his life against arrogant dogma and belief in one sole truth. Few credible thinkers rival Carneades in their rigorous skepticism (a class that would include the medieval Arab philosopher Al Gazali, Hume, and Kant—but only Popper came to elevate his skepticism to an all-encompassing scientific methodology). As the skeptics’ main teaching was that nothing could be accepted with certainty, conclusions of various degrees of probability could be formed, and these supplied a guide to conduct.

Taleb holds that Cicero engaged in probabilistic reasoning:

He preferred to be guided by probability than allege with certainty—very handy, some said, because it allowed him to contradict himself. This may be a reason for us, who have learned from Popper how to remain self critical, to respect him more, as he did not hew stubbornly to an opinion for the mere fact that he had voiced it in the past.

Taleb asserts that the speculator George Soros has a wonderful ability to change his opinions rather quickly. In fact, without this ability, Soros could not have become so successful as a speculator. There are many stories about Soros holding one view strongly, only to abandon it very quickly and take the opposite view, leading to a large profit where there otherwise would have been a large loss.

Most of us tend to become married to our favorite ideas. Most of us are not like George Soros. Especially after we have invested time and energy into developing some idea.

At the extreme, just imagine a scientist who spent years developing some idea. Many scientists in that situation have a hard time abandoning their idea, even after there is good evidence that they’re wrong. That’s why it is said that science evolves from funeral to funeral.

FOURTEEN: BACCHUS ABANDONS ANTONY

Taleb refers to C.P. Cavafy’s poem, Apoleipein o Theos Antonion (The God Abandons Antony). The poem addresses Antony after he has been defeated. Taleb comments:

There is nothing wrong and undignified with emotions—we are cut to have them. What is wrong is not following the heroic, or at least, the dignified path. That is what stoicism means. It is the attempt by man to get even with probability.

Taleb concludes with some advice (stoicism):

Dress at your best on your execution day (shave carefully); try to leave a good impression on the death squad by standing erect and proud. Try not to play victim when diagnosed with cancer (hide it from others and only share the information with the doctor—it will avert the platitudes and nobody will treat you like a victim worthy of their pity; in addition the dignified attitude will make both defeat and victory feel equally heroic). Be extremely courteous to your assistant when you lose money (instead of taking it out on him as many of the traders whom I scorn routinely do). Try not to blame others for your fate, even if they deserve blame. Never exhibit any self pity, even if your significant other bolts with the handsome ski instructor or the younger aspiring model. Do not complain… The only article Lady Fortuna has no control over is your behavior.

BOOLE MICROCAP FUND

An equal weighted group of micro caps generally far outperforms an equal weighted (or cap-weighted) group of larger stocks over time. See the historical chart here: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

This outperformance increases significantly by focusing on cheap micro caps. Performance can be further boosted by isolating cheap microcap companies that show improving fundamentals. We rank microcap stocks based on these and similar criteria.

There are roughly 10-20 positions in the portfolio. The size of each position is determined by its rank. Typically the largest position is 15-20% (at cost), while the average position is 8-10% (at cost). Positions are held for 3 to 5 years unless a stock approaches intrinsic value sooner or an error has been discovered.

The mission of the Boole Fund is to outperform the S&P 500 Index by at least 5% per year (net of fees) over 5-year periods. We also aim to outpace the Russell Microcap Index by at least 2% per year (net). The Boole Fund has low fees.

If you are interested in finding out more, please e-mail me or leave a comment.

My e-mail: jb@boolefund.com

Disclosures: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this article may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of Boole Capital, LLC.

world is changing

Love watching movies !