February 20, 2022

Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee are the authors of The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (Norton, 2014). It’s one of the best books I’ve read in the past few years.

The second machine age is going to bring enormous progress to economies and societies. Total wealth – whether defined narrowly or much more broadly – will increase significantly. But we do have to ensure that political and social structures are properly adjusted so that everyone can benefit from massive technological progress.

The first six chapters – starting with The Big Stories, and going thru Artificial and Human Intelligence in the Second Machine Age – give many examples of recent technological progress.

The five subsequent chapters – four of which are covered here – discuss the bounty and the spread.

Bounty is the increase in volume, variety, and quality and the decrease in cost of the many offerings brought on by modern technological progress. It’s the best economic news in the world today.

Spread is differences among people in economic success.

The last four chapters discuss what interventions could help maximize the bounty while mitigating the effects of the spread.

Here are the chapters covered:

- The Big Stories

- The Skills of the New Machines: Technology Races Ahead

- Moore’s Law and the Second Half of the Chessboard

- The Digitization of Just About Everything

- Innovation: Declining or Recombining?

- Artificial and Human Intelligence in the Second Machine Age

- Computing Bounty

- Beyond GDP

- The Spread

- Implications of the Bounty and the Spread

- Learning to Race With Machines: Recommendations for Individuals

- Policy Recommendations

- Long-term Recommendations

- Technology and the Future

THE BIG STORIES

Freeman Dyson:

Technology is a gift of God. After the gift of life, it is perhaps the greatest of God’s gifts. It is the mother of civilizations, of arts and of sciences.

James Watt’s brilliant tinkering with the steam engine in 1775 and 1776 was central to the Industrial Revolution:

The Industrial Revolution, of course, is not only the story of steam power, but steam started it all. More than anything else, it allowed us to overcome the limitations of muscle power, human and animal, and generate massive amounts of useful energy at will. This led to factories and mass production, to railways and mass transportation. It led, in other words, to modern life. The Industrial Revolution ushered in humanity’s first machine age – the first time our progress was driven primarily by technological innovation – and it was the most profound time of transformation the world has ever seen. (pages 6-7)

(Note that Brynjolfsson and McAfee refer to the Industrial Revolution as “the first machine age.” And they refer to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as the Second Industrial Revolution.)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee continue:

Now comes the second machine age. Computers and other digital advances are doing for mental power – the ability to use our brains to understand and shape our environments – what the steam engine and its descendants did for muscle power. They’re allowing us to blow past previous limitations and taking us into new territory. How exactly this transition will play out remains unknown, but whether or not the new machine age bends the curve as Watt’s steam engine, it is a very big deal indeed. This book explains how and why.

For now, a very short and simple answer: mental power is at least as important for progress and development – for mastering our physical and intellectual environment to get things done – as physical power. So a vast and unprecedented boost to mental power should be a great boost to humanity, just as the earlier boost to physical power so clearly was. (pages 7-8)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee admit that recent technological advances surpassed their expectations:

We wrote this book because we got confused. For years we have studied the impact of digital technologies like computers, software, and communications networks, and we thought we had a decent understanding of their capabilities and limitations. But over the past few years they started surprising us. Computers started diagnosing diseases, listening and speaking to us, and writing high-quality prose, while robots started scurrying around warehouses and driving cars with minimal or no guidance. Digital technologies had been laughably bad at a lot of these things for a long time – then they suddenly got very good. How did this happen? And what were the implications of this progress, which was astonishing and yet came to be considered a matter of course?

Brynjolfsson and McAfee did a great deal of reading. But they learned the most by speaking with inventors, investors, entrepreneurs, engineers, scientists, and others making or using technology.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee report that they reached three broad conclusions:

The first is that we’re living at a time of astonishing progress with digital technologies – those that have computer hardware, software, and networks at their core. These technologies are not brand-new; businesses have been buying computers for more than half a century… But just as it took generations to improve the steam engine to the point that it could power the Industrial Revolution, it’s also taken time to refine our digital engines.

We’ll show why and how the full force of these technologies has recently been achieved and give examples of its power. ‘Full,’ though, doesn’t mean ‘mature.’ Computers are going to continue to improve and do new and unprecedented things. By ‘full force,’ we mean simply that the key building blocks are already in place for digital technologies to be as important and transformational for society and the economy as the steam engine. In short, we’re at an inflection point – a point where the curve starts to bend a lot – because of computers. We are entering a second machine age.

Our second conclusion is that the transformations brought about by digital technology will be profoundly beneficial ones. We’re heading into an era that won’t just be different; it will be better, because we’ll be able to increase both the variety and the volume of our consumption… we don’t just consume calories and gasoline. We also consume information from books and friends, entertainment from superstars and amateurs, expertise from teachers and doctors, and countless other things that are not made of atoms. Technology can bring us more choice and even freedom.

When these things are digitized – when they’re converted into bits that can be stored on a computer and sent over a network – they acquire some weird and wonderful properties. They’re subject to different economics, where abundance is the norm rather than scarcity. As we’ll show, digital goods are not like physical ones, and these differences matter.

…Digitization is improving the physical world, and these improvements are only going to become more important. Among economic historians, there’s wide agreement that, as Martin Weitzman puts it, ‘the long-term growth of an advanced economy is dominated by the behavior of technical progress.’ As we’ll show, technical progress is improving exponentially.

Our third conclusion is less optimistic: digitization is going to bring with it some thorny challenges… Technological progress is going to leave behind some people, perhaps even a lot of people, as it races ahead. As we’ll demonstrate, there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education, because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only ‘ordinary’ skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate. (pages 9-11)

THE SKILLS OF THE NEW MACHINES: TECHNOLOGY RACES AHEAD

Arthur C. Clarke:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Computers are symbol processors, note Brynjolfsson and McAfee: Their circuitry can be interpreted in the language of ones and zeroes, or as true or false, or as yes or no.

Computers are especially good at following rules or algorithms. So computers are especially well-suited for arithmetic, logic, and similar tasks.

Historically, computers have not been very good at pattern recognition compared to humans. Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

Our brains are extraordinarily good at taking in information via our senses and examining it for patterns, but we’re quite bad at describing or figuring out how we’re doing it, especially when a large volume of fast-changing information arrives at a rapid pace. As the philosopher Michael Polanyi famously observed, ‘We know more than we can tell.’ (page 18)

Driving a car is an example where humans’ ability to recognize patterns in a mass of sense data was thought to be beyond a computer’s ability. DARPA – the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency – held a Grand Challenge for driverless cars in 2004. It was a 150-mile course through the Mojave Desert in California. There were fifteen entrants. Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

The results were less than encouraging. Two vehicles didn’t make it to the starting area, one flipped over in the starting area, and three hours into the race, only four cars were still operational. The ‘winning’ Sandstorm car from Carnegie Mellon University covered 7.4 miles (less than 5 percent of the total) before veering off the course during a hairpin turn and getting stuck on an embankment. The contest’s $1 million prize went unclaimed, and Popular Science called the event ‘DARPA’s Debacle in the Desert.’ (page 19)

Within a few years, however, driverless cars became far better. By 2012, Google driverless cars had covered hundreds of thousands of miles with only two accidents (both caused by humans). Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

Progress on some of the oldest and toughest challenges associated with computers, robots, and other digital gear was gradual for a long time. Then in the past few years it became sudden; digital gear started racing ahead, accomplishing tasks it had always been lousy at and displaying skills it was not supposed to acquire any time soon. (page 20)

Another example of an area where it was thought fairly recently that computers wouldn’t become very good is complex communication. But starting around 2011, computers suddenly seemed to get much better at using human languages to communicate with humans. Robust natural language processing has become available to people with smartphones.

For instance, there are mobile apps that show you an accurate map and that tell you the fastest way for getting somewhere. Also, Google’s translations on twitter have gotten much better recently (as of mid-2017).

In 2011, IBM’s supercomputer Watson beat Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter at Jeopardy! This represented another big advance in which a computer combined pattern matching with complex communication. The game involves puns, rhymes, wordplay, and more.

Jennings had won a record seventy-four times in a row in 2004. Rutter beat Jennings in the 2005 Ultimate Tournament of Champions. The early versions of IBM’s Watson came nowhere close to winning Jeopardy! But when Watson won in 2011, it had three times as much money as either human opponent. Jennings later remarked:

Just as factory jobs were eliminated in the twentieth century by new assembly-line robots, Brad and I were the first knowledge-industry workers put out of work by the new generation of ‘thinking’ machines. (page 27)

Robotics is another area where progress had been gradual, but recently became sudden, observe Brynjolfsson and McAfee. Robot entered the English language via a 1921 Czech play, R.U.R. (Rossum’s “Universal” Robots), by Karel Capek. Isaac Asimov coined the term robotics in 1941.

Robots have still lagged in perception and mobility, while excelling in many computational tasks. This dichotomy is known as Moravec’s paradox, described on Wikipedia as:

the discovery by artificial intelligence and robotics researchers that, contrary to traditional assumptions, high-level reasoning requires very little computation, but low-level sensorimotor skills require enormous computational resources. (pages 28-29)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee write that, at least until recently, most robots in factories could only handle items that showed up in exactly the same location and configuration each time. To perform a different task, these robots would need to be reprogrammed.

In 2008, Rodney Brooks founded Rethink Robotics. Brooks would like to create robots that won’t need to be programmed by engineers. These new robots could be taught to do a task, or re-taught a new one, by shop floor workers. At the company’s headquarters in Boston, Brynjolfsson and McAfee got a sneak peak at a new robot – Baxter. It has two arms with claw-like grips. The head is an LCD face. It has wheels instead of legs. Each arm can be manually trained to do a wide variety of tasks.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

Kiva, another young Boston-area company, has taught its automatons to move around warehouses safely, quickly, and effectively. Kiva robots look like metal ottomans or squashed R2-D2’s. They scuttle around buildings at about knee-height, staying out of the way of humans and one another. They’re low to the ground so they can scoot underneath shelving units, lift them up, and bring them to human workers. After these workers grab the products they need, the robot whisks the shelf away and another shelf-bearing robot takes its place. Software tracks where all the products, shelves, robots, and people are in the warehouse, and orchestrates the continuous dance of the Kiva automatons. In March of 2012, Kiva was acquired by Amazon – a leader in advanced warehouse logistics – for more than $750 million in cash. (page 32)

Boston Dynamics, another New England startup, has built dog-like robots to support troops in the field.

A final example is the Double, which is essentially an iPad on wheels. It allows the operator to see and hear what the robot does.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee present more evidence of technological progress:

On the Star Trek television series, devices called tricorders were used to scan and record three kinds of data: geological, meteorological, and medical. Today’s consumer smartphones serve all these purposes; they can be put to work as seismographs, real-time weather radar maps, and heart- and breathing-rate monitors. And, of course, they’re not limited to these domains. They also work as media players, game platforms, reference works, cameras, and GPS devices. (page 34)

Recently, the company Narrative Science was contracted with by Forbes.com in order to write earnings previews that are indistinguishable from human writing.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee conclude:

Most of the innovations described in this chapter have occurred in just the past few years. They’ve taken place where improvement had been frustratingly slow for a long time, and where the best thinking often led to the conclusion that it wouldn’t speed up. But then digital progress became sudden after being gradual for so long. This happened in multiple areas, from artificial intelligence to self-driving cars to robotics.

How did this happen? Was it a fluke – a confluence of a number of lucky, one-time advances? No, it was not. The digital progress we’ve seen recently certainly is impressive, but it’s just a small indication of what’s to come. It’s the dawn of the second machine age. To understand why it’s unfolding now, we need to understand the nature of technological progress in the era of digital hardware, software, and networks. In particular, we need to understand its three characteristics: that it is exponential, digital, and combinatorial. The next three chapters will discuss each of these in turn. (page 37)

MOORE’S LAW AND THE SECOND HALF OF THE CHESSBOARD

Moore’s Law roughly says that computing power per dollar doubles about every eighteen months. It’s not a law of nature, note Brynjolfsson and McAfee, but a statement about the continued productivity of the computer industry’s engineers and scientists. Moore first made his prediction in 1965. He thought it would only last for ten years. But it’s now lasted almost fifty years.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee point out that this kind of sustained progress hasn’t happened in any other field. It’s quite remarkable.

Inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil has told the story of the inventor and the emperor. In the 6th century in India, a clever man invented the game of chess. The man went to the capital city, Pataliputra, to present his invention to the emperor. The emperor was so impressed that he asked the man to name his reward.

The inventor praised the emperor’s generosity and said, “All I desire is some rice to feed my family.” The inventor then suggested they use the chessboard to determine the amount of rice he would receive. He said to place one grain of rice on the first square, two grains on the second square, four grains on the third square, and so forth. The emperor readily agreed.

If you were to actually do this, you would end up with more than eighteen quintillion grains of rice. Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

A pile of rice this big would dwarf Mount Everest; it’s more rice than has been produced in the history of the world. (pages 45-46)

Kurzweil points out that when you get to the thirty-second square – which is the first half of the chessboard – you have about 4 billion grains of rice, or one large field’s worth. But when you get to the second half of the chessboard, the result of sustained exponential growth becomes clear.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

Our quick doubling calculation also helps us understand why progress with digital technologies feels so much faster these days and why we’ve seen so many recent examples of science fiction becoming business reality. It’s because the steady and rapid exponential growth of Moore’s Law has added up to the point that we’re now in a different regime of computing: we’re now in the second half of the chessboard. The innovations we described in the previous chapter – cars that drive themselves in traffic; Jeopardy!-champion supercomputers; auto-generated news stories; cheap, flexible factory robots; and inexpensive consumer devices that are simultaneously communicators, tricorders, and computers – have all appeared since 2006, as have countless other marvels that seem quite different from what came before.

One of the reasons they’re all appearing now is that the digital gear at their hearts is finally both fast and cheap enough to enable them. This wasn’t the case just a decade ago. (pages 47-48)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee later add:

It’s clear that many of the building blocks of computing – microchip density, processing speed, storage capacity, energy efficiency, download speed, and so on – have been improving at exponential rates for a long time. (page 49)

For example, in 1996, the ASCI Red supercomputer cost $55 million to develop and took up 1,600 square feet of floor space. It was the first computer to score above one teraflop – one trillion floating point operations per second – on the standard test for computer speed, note Brynjolfsson and McAfee. It used eight hundred kilowatts per hour, roughly as much as eight hundred homes. By 1997, it reached 1.8 teraflops.

Nine years later, the Sony PlayStation 3 hit 1.8 teraflops. It cost five hundred dollars, took up less than a tenth of a square meter, and used about two hundred watts, observe Brynjolfsson and McAfee.

Exponential progress has made possible many of the advances discussed in the previous chapter. IBM’s Watson draws on a plethora of clever algorithms, but it would be uncompetitive without computer hardware about one hundred times more powerful than Deep Blue, its chess-playing predecessor that beat the human world champion, Garry Kasparov, in a 1997 match. (page 50)

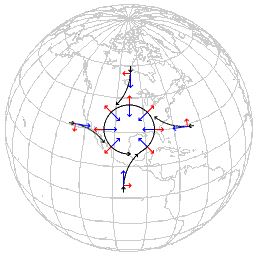

SLAM

Researchers in artificial intelligence have long been interested in SLAM – simultaneous localization and mapping. As of 2008, computers weren’t able to do this well for large areas.

In November 2010, Microsoft offered Kinect – a $150 accessory – as an addition to its Xbox gaming platform.

The Kinect could keep track of two active players, monitoring as many as twenty joints on each. If one player moved in front of the other, the device made a best guess about the obscured person’s movements, then seamlessly picked up all joints once he or she came back into view. Kinect could also recognize players’ faces, voices, and gestures and do so across a wide range of lighting and noise conditions. It accomplished this with digital sensors including a microphone array (which pinpointed the source of sound better than a single microphone could), a standard video camera, and a depth perception system that both projected and detected infrared light. Several onboard processors and a great deal of proprietary software converted the output of these sensors into information that game designers could use. (page 53)

After its release, Kinect sold more than eight million units in sixty days, which makes it the fastest-selling consumer electronics device of all time. But the Kinect system could do far more than its video game applications. In August 2011, at the SIGGRAPH (the Association of Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Graphics and Interactive Techniques) in Vancouver, British Columbia, a Microsoft team introduced KinestFusion as a solution to SLAM.

In a video shown at SIGGRAPH 2011, a person picks up a Kinect and points it around a typical office containing chairs, a potted plant, and a desktop computer and monitor. As he does, the video splits into multiple screens that show what the Kinect is able to sense. It immediately becomes clear that if the Kinect is not completely solving the SLAM for the room, it’s coming close. In real time, Kinect draws a three-dimensional map of the room and all the objects in it, including a coworker. It picks up the word DELL pressed into the plastic on the back of the computer monitor, even though the letters are not colored and only one millimeter deeper than the rest of the monitor’s surface. The device knows where it is in the room at all times, and even knows how virtual ping-pong balls would bounce around if they were dropped into the scene. (page 54)

Microsoft made available (in June 2011) a Kinect software development kit. Less than a year later, a team led by John Leonard of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab announced Kintinuous, a ‘spatially extended’ version of KinectFusion. Users could scan large indoor volumes and even outdoor environments.

Another fascinating example of powerful digital sensors:

A Google autonomous car incorporates several sensing technologies, but its most important ‘eye’ is a Cyclopean LIDAR (a combination of ‘LIght’ and ‘raDAR’) assembly mounted on the roof. This rig, manufactured by Velodyne, contains sixty-four separate laser beams and an equal number of detectors, all mounted in a housing that rotates ten times a second. It generates about 1.3 million data points per second, which can be assembled by onboard computers into a real-time 3D picture extending one hundred meters in all directions. Some early commercial LIDAR systems around the year 2000 cost up to $35 million, but in mid-2013 Velodyne’s assembly for self-navigating vehicles was priced at approximately $80,000, a figure that will fall much further in the future. David Hall, the company’s founder and CEO, estimates that mass production would allow his product’s price to ‘drop to the level of a camera, a few hundred dollars.’ (page 55)

THE DIGITIZATION OF JUST ABOUT EVERYTHING

As of March 2017, Android users could choose from 2.8 million applications while Apple users could choose from 2.2 million. One example of a free but powerful app – a version of which is available from several companies – is one that gives you a map plus driving directions. The app tells you the shortest route available now.

Digitization is turning all kinds of information and bits into the language of computers – ones and zeroes. What’s crucial about digital information is that it’s non-rival and it has close to zero marginal cost of reproduction. In other words, it can be used over and over – it doesn’t get ‘used up’ – and it’s extremely cheap to make another copy. (Rival goods, by contrast, can only be used by one person at a time.)

In 1991, at the Nineteenth General Conference on Weights and Measures, the set of prefixes was expanded to include a yotta, representing one septillion, or 10^24. As of 2012, there were 2.7 zettabytes of digital data – or 2.7 sextillion bytes. This is only one prefix away from a yotta.

The explosion of digital information, while obviously not always useful, can often lead to scientific advances – i.e., understanding and predicting phenomena more accurately or more simply. Some search terms have been found to have predictive value. Same with some tweets. Culturonomics makes use of digital information – like scanned copies of millions of books written over the centuries – to study human culture.

INNOVATION: DECLINING OR RECOMBINING?

Linus Pauling:

If you want to have good ideas, you must have many ideas.

Innovation is the essential long-term driver of progress. As Paul Krugman said:

Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. (page 72)

Improving the standard of living over time depends almost entirely on raising output per worker, Krugman explained. Brynjolfsson and McAfee write that most economists agree with Joseph Schumpeter’s observation:

Innovation is the outstanding fact in the economic history of capitalist society… and also it is largely responsible for most of what we would at first sight attribute to other factors. (page 73)

The original Industrial Revolution resulted in large part from the steam engine. The Second Industrial Revolution depended largely on three innovations: electricity, the internal combustion engine, and indoor plumbing with running water.

Economist Robert Gordon, a widely respected researcher on productivity and economic growth, has concluded that by 1970, economic growth stalled out. The three main inventions of the Second Industrial Revolution had their effect from 1870 to 1970. But there haven’t been economically significant innovations since 1970, according to Gordon. Some other economists, such as Tyler Cowen, agree with Gordon’s basic view.

The most economically important innovations are called general purposes technologies (GPTs). GPTs, according to Gavin Wright, are:

deep new ideas or techniques that have the potential for important impacts on many sectors of the economy. (page 76)

‘Impacts,’ note Brynjolfsson and McAfee, mean significant boosts in output due to large productivity gains. They noticeably accelerate economic progress. GPTs, economists have concurred, should be pervasive, improving over time, and should lead to new innovations.

Isn’t information and communication technology (ICT) a GPT? Most economic historians think so. Economist Alexander Field compiled a list of candidates for GPTs, and ICT was tied with electricity as the second most common GPT. Only the steam engine was ahead of ICT.

Not everyone agrees. Cowen argues basically that ICT is coming up short on the revenue side of things.

The ‘innovation-as-fruit’ view, say Brynjolfsson and McAfee, is that there are discrete inventions followed by incremental improvements, but those improvements stop being significant after a certain point. The original inventions have been used up.

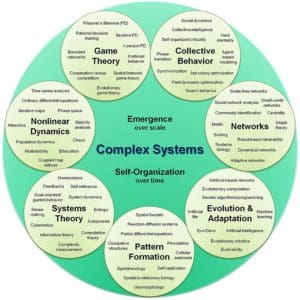

Another way to look at innovation, however, is not coming up with something big and new, but recombining things that already exist. Complexity scholar Brian Arthur holds this view of innovation. So does economist Paul Romer, who has written that we, as humans, nearly always underestimate how many new ideas have yet to be discovered.

The history of physics may serve as a good illustration of Romer’s point. At many different points in the history of physics, at least some leading physicists have asserted that physics was basically complete. This has always been dramatically wrong. As of 2017, is physics closer to 10% complete or 90% complete? Of course, no one knows for sure. But how much more will be discovered and invented if we have AI with IQ 1,000,000+ being handled by genetically engineered scientists? In my view, physics is probably closer to 10% complete.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee point out that ICT leads to recombinant innovation, perhaps like nothing else has.

…digital innovation is recombinant innovation in its purest form. Each development becomes a building block for future innovations. Progress doesn’t run out; it accumulates… Moore’s Law makes computing devices and sensors exponentially cheaper over time, enabling them to be built economically into more and more gear, from doorknobs to greeting cards. Digitization makes available massive bodies of data relevant to almost any situation, and this information can be infinitely reproduced and reused because it is non-rival. As a result of these two forces, the number of potentially valuable building blocks is exploding around the world, and the possibilities are multiplying as never before. We’ll call this the ‘innovation-as-building-block’ view of the world; it’s the one held by Arthur, Romer, and the two of us. From this perspective, unlike the innovation-as-fruit view, building blocks don’t ever get eaten or otherwise used up. In fact, they increase the opportunities for future recombinations.

…In his paper, ‘Recombinant Growth,’ the economist Martin Weitzman developed a mathematical model of new growth theory in which the ‘fixed factors’ in an economy – machine tools, trucks, laboratories, and so on – are augmented over time by pieces of knowledge that he calls ‘seed ideas,’ and knowledge itself increases over time as previous seed ideas are recombined into new ones. (pages 81-82)

As the number of seed ideas increases, the combinatorial possibilities explode quickly. Weitzman:

In the early stages of development, growth is constrained by number of potential new ideas, but later on it is constrained only by the ability to process them.

ICT connects nearly everyone, and computing power continues to follow Moore’s Law. Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

We’re interlinked by global ICT, and we have affordable access to masses of data and vast computing power. Today’s digital environment, in short, is a playground for large-scale recombination. (page 83)

…

…The innovation scholars Lars Bo Jeppesen and Karim Lakhani studied 166 scientific problems posted to Innocentive, all of which had stumped their home organizations. They found that the crowd assembled around Innocentive was able to solve forty-nine of them, for a success rate of nearly 30 percent. They also found that people whose expertise was far away from the apparent domain of the problem were more likely to submit winning solutions. In other words, it seemed to actually help a solver to be ‘marginal’ – to have education, training, and experience that were not obviously relevant for the problem. (page 84)

Kaggle is similar to Innocentive, but Kaggle is focused on data-intensive problems with the goal being to improve the baseline prediction. The majority of Kaggle contests, says Brynjolfsson and McAfee, are won by people who are marginal to the domain of the challenge. In one problem involving artificial intelligence – computer grading of essays – none of the top three finishers had any formal training in artificial intelligence beyond a free online course offered by Stanford AI faculty, open to anyone in the world.

ARTIFICIAL AND HUMAN INTELLIGENCE IN THE SECOND MACHINE AGE

Previous chapters discussed three forces – sustained exponential improvement in most aspects of computing, massive amounts of digitized information, and recombinant invention – that are yielding significant innovations. But, state Brynjolfsson and McAfee, when you consider also that most people on the planet are connected via the internet and that useful artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging, you have to be even more optimistic about future innovations.

Digital technologies will restore hearing to the deaf via cochlear implants. Digital technologies will likely restore sight to the fully blind, perhaps by retinal implants. That’s just the beginning, to say nothing of advances in biosciences. Dr. Watson will become the best diagnostician in the world. Another supercomputer will become the best surgeon in the world.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee summarize:

The second machine age will be characterized by countless instances of machine intelligence and billions of interconnected brains working together to better understand and improve our world. (page 96)

COMPUTING BOUNTY

Milton Friedman:

Most economic fallacies derive from the tendency to assume that there is a fixed pie, that one party can gain only at the expense of another.

Productivity growth comes from technological innovation and from improvements in production techniques. The 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s were a time of rapid productivity growth. The technologies of the first machine age, such as electricity and the internal combustion engine, were largely responsible.

But in 1973, things slowed down. What’s interesting is that computers were becoming available during this decade. But like the chief innovations of the first machine age, it would take a few decades before computing would begin to impact productivity growth significantly.

The internet started impacting productivity within a decade after its invention in 1989. And even more importantly, enterprise-wide IT systems boosted productivity in the 1990s. Firms that used IT throughout the 1990s were noticeably more productive as a result.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

The first five years of the twenty-first century saw a renewed wave of innovation and investment, this time less focused on computer hardware and more focused on a diversified set of applications and process innovations… In a statistical study of over six hundred firms that Erik did with Lorin Hitt, he found that it takes an average of five to seven years before full productivity benefits of computers are visible in the productivity of the firms making the investments. This reflects the time and energy required to make the other complementary investments that bring a computerization effort success. In fact, for every dollar of investment in computer hardware, companies need to invest up to another nine dollars in software, training, and business process redesign. (pages 104-105)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee conclude:

The explanation for this productivity surge is in the lags that we always see when GPTs are installed. The benefits of electrification stretched for nearly a century as more and more complementary innovations were implemented. The digital GPTs of the second machine age are no less profound. Even if Moore’s Law ground to a halt today, we could expect decades of complementary innovations to unfold and continue to boost productivity. However, unlike the steam engine or electricity, second machine age technologies continue to improve at a remarkably rapid exponential pace, replicating their power with digital perfection and creating even more opportunities for combinatorial innovation. The path won’t be smooth… but the fundamentals are in place for bounty that vastly exceeds anything we’ve ever seen before. (page 106)

BEYOND GDP

Brynjolfsson and McAfee note that President Hoover had to rely on data such as freight car loadings, commodity prices, and stock prices in order to try to understand what was happening during the Great Depression.

The first set of national accounts was presented to Congress in 1937 based on the pioneering work of Nobel Prize winner Simon Kuznets, who worked with researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research and a team at the U.S. Department of Commerce. The resulting set of metrics served as beacons that helped illuminate many of the dramatic changes that transformed the economy throughout the twentieth century.

But as the economy has changed, so, too, must our metrics. More and more what we care about in the second machine age are ideas, not things – mind, not matter; bits, not atoms; and interactions, not transactions. The great irony of this information age is that, in many ways, we know less about the sources of value in the economy than we did fifty years ago. In fact, much of the change has been invisible for a long time simply because we did not know what to look for. There’s a huge layer of the economy unseen in the official data and, for that matter, unaccounted for on the income statements and balance sheets of most companies. Free digital goods, the sharing economy, intangibles and changes in our relationships have already had big effects on our well-being. They also call for new organizational structures, new skills, new institutions, and perhaps even a reassessment of some of our values. (pages 108-109)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee write:

In addition to their vast library of music, children with smartphones today have access to more information in real time via the mobile web than the president of the United States had twenty years ago. Wikipedia alone claims to have over fifty times as much information as Encyclopaedia Britannica, the premier compilation of knowledge for most of the twentieth century. Like Widipedia but unlike Britannica, much of the information and entertainment available today is free, as are over one million apps on smartphones.

Because they have zero price, these services are virtually invisible in the official statistics. They add value to the economy but not dollars to GDP. And because our productivity data are, in turn, based on GDP metrics, the burgeoning availability of free goods does not move the productivity dial. There’s little doubt, however, that they have real value. (pages 110-111)

Free products can push GDP downward. A free online encyclopedia available for pennies instead of thousands of dollars makes you better off, but it lowers GDP, observe Brynjolfsson and McAfree. GDP was a good measure of economic growth throughout most of the twentieth century. Higher levels of production generally led to greater well-being. But that’s no longer true to the same extent due to the proliferation of digital goods that do not have a dollar price.

One way to measure the value of goods that are free or nearly free is to find out how much people would be willing to pay for them. This is known as consumer surplus, but in practice it’s extremely difficult to measure.

New goods and services have not been fully captured in GDP figures.

For the overall economy, the official GDP numbers miss the value of new goods and services added to the tune of about 0.4 percent of additional growth each year, according to economist Robert Gordon. Remember that productivity growth has been in the neighborhood of 2 percent per year for most of the past century, so contribution of new goods is not a trivial portion. (pages 117-118)

GDP misses the full value of digital goods and services. Similarly, intangible assets are not fully measured.

Just as free goods rather than physical products are an increasingly important share of consumption, intangibles also make up a growing share of the economy’s capital assets. Production in the second machine age depends less on physical equipment and structures and more on the four categories of intangible assets: intellectual property, organizational capital, user-generated content, and human capital. (page 119)

Paul Samuelson and Bill Nordhaus have observed that GDP is one of the great inventions of the twentieth century. But as Brynjolfsson and McAfee indicate, digital innovation means that we also need innovation in our economic metrics.

The new metrics will differ both in conception and execution. We can build on some of the existing surveys and techniques researchers have been using. For instance, the human development index uses health and education statistics to fill in some of the gaps in official GDP statistics; the multidimensional poverty index uses ten different indicators – such as nutrition, sanitation, and access to water – to assess well-being in developing countries. Childhood death rates and other health indicators are recorded in other periodic household surveys like the Demographic and Health Surveys.

There are several promising projects in this area. Joe Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi have created a detailed guide for how we can do a comprehensive overhaul of our economic statistics. Another promising project is the Social Progress Index that Michael Porter, Scott Stern, Roberto Lauria, and their colleagues are developing. In Bhutan, they’ve begun measuring ‘Gross National Happiness.’ There is also a long-running poll behind the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index.

These are all important improvements, and we heartily support them. But the biggest opportunity is in using the tools of the second machine age itself: the extraordinary volume, variety, and timeliness of data available digitally. The Internet, mobile phones, embedded sensors in equipment, and a plethora of other sources are delivering data continuously. For instance, Roberto Rigobon and Alberto Cavallo measure online prices from around the world on a daily basis to create an inflation index that is far timelier and, in many cases, more reliable, than official data gathered via monthly surveys with much smaller samples. Other economists are using satellite mapping of nighttime artificial light sources to estimate economic growth in different parts of the world, and assessing the frequency of Google searches to understand changes in unemployment and housing. Harnessing this information will produce a quantum leap in our understanding of the economy, just as it has already changed marketing, manufacturing, finance, retailing, and virtually every other aspect of business decision-making.

As more data become available, and the economy continues to change, the ability to ask the right questions will become even more vital. No matter how bright the light is, you won’t find your keys by searching under a lamppost if that’s not where you lost them. We must think hard about what it is we really value, what we want more of, and what we want less of. GDP and productivity growth are important, but they are a means to an end and not ends in and of themselves. Do we want to increase consumer surplus? Then lower prices or more leisure might be signs of progress, even if they result in a lower GDP. And, of course, many of our goals are nonmonetary. We shouldn’t ignore the economic metrics, but neither should we let them crowd out our other values simply because they are more measurable.

In the meantime, we need to bear in mind that the GDP and productivity statistics overlook much of what we value, even when using a narrow economic lens. What’s more, the gap between what we measure and what we value grows every time we gain access to a new good or service that never existed before, or when existing goods become free as they so often do when they are digitized. (pages 123-124)

THE SPREAD

Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

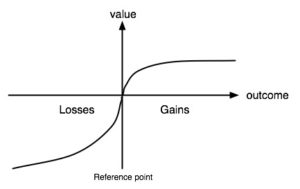

…Advances in technology, especially digital technologies, are driving an unprecedented reallocation of wealth and income. Digital technologies can replicate valuable ideas, insights, and innovations at very low cost. This creates bounty for society and wealth for innovators, but diminishes the demand for previously important types of labor, which can leave many people with reduced incomes.

The combination of bounty and spread challenges two common though contradictory worldviews. One common view is that advances in technology always boost incomes. The other is that automation hurts workers’ wages as people are replaced by machines. Both of these have a kernel of truth, but the reality is more subtle. Rapid advances in our digital tools are creating unprecedented wealth, but there is no economic law that says all workers, or even a majority of workers, will benefit from these advances.

For almost two hundred years, wages did increase alongside productivity. This created a sense of inevitability that technology helped (almost) everyone. But more recently, median wages have stopped tracking productivity, underscoring the fact that such a decoupling is not only a theoretical possibility but also an empirical fact in our current economy. (page 128)

Statistics on how the median worker is doing versus the top 1 percent are revealing:

…The year 1999 was the peak year for real (inflation-adjusted) income of the median American household. It reached $54,932 that year, but then started falling. By 2011, it had fallen nearly 10 percent to $50,054, even as overall GDP hit a record high. In particular, wages of unskilled workers in the United States and other advanced countries have trended downward.

Meanwhile, for the first time since the Great Depression, over half the total income in the United States went to the top 10 percent of Americans in 2012. The top 1 percent earned over 22 percent of income, more than doubling their share since the early 1980s. The share of income going to the top hundredth of one percent of Americans, a few thousand people with annual incomes over $1 million, is now at 5.5 percent, after increasing more between 2011 and 2012 than any year since 1927-1928. (page 129)

Technology is changing economics. Brynjolfsson and McAfee point out two examples: digital photography and TurboTax.

At one point, Kodak employed 145,300 people. But recently, Kodak filed for bankruptcy. Analog photography peaked in the year 2000. As of 2014, over 2.5 billion people had digital cameras and the vast majority of photos are digital. At the same time, Facebook has a market value many times what Kodak ever did. And Facebook has created at least several billionaires, each of whom has a net worth more than ten times what George Eastman – founder of Kodak – had. Also, in 2012, Facebook had over one billion users, despite employing only 4,600 people (roughly 1,000 of whom are engineers).

Just as digital photography has made it far easier for many people to take and store photos, so TurboTax software has made it much more convenient for many people to file their taxes. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of tax preparers – including those at H&R Block – have had their jobs and incomes threatened. But the creators of TurboTax have done very well – one is a billionaire.

The crucial reality from the standpoint of economics is that it takes a relatively small number of designers and engineers to create and update a program like TurboTax. As we saw in chapter 4, once the algorithms are digitized they can be replicated and delivered to millions of users at almost zero cost. As software moves to the core of every industry, this type of production process and this type of company increasingly populates the economy. (pages 130-131)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee report that most Americans have become less wealthy over the past several decades.

Between 1983 and 2009, Americans became vastly wealthier overall as the total value of their assets increased. However, as noted by economists Ed Wolff and Sylvio Allegretto, the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution actually saw a net decrease in their wealth. Taken as a group, the top 20 percent got not 100 percent of the increase, but more than 100 percent. Their gains included not only the trillions of dollars of wealth newly created in the economy but also some additional wealth that was shifted in their direction from the bottom 80 percent. The distribution was also highly skewed even among relatively wealthy people. The top 5 percent got 80 percent of the nation’s wealth increase; the top 1 percent got over half of that, and so on for ever-finer subdivisions of the wealth distribution…

Along with wealth, the income distribution has also shifted. The top 1 percent increased their earnings by 278 percent between 1979 and 2007, compared to an increase of just 35 percent for those in the middle of the income distribution. The top 1 percent earned over 65 percent of the income between 2002 and 2007. (page 131)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee then add:

As we discussed in our earlier book Race Against the Machine, these structural economic changes have created three overlapping pairs of winners and losers. As a result, not everyone’s share of the economic pie is growing. The first two sets of winners are those who have accumulated significant quantities of the right capital assets. These can be either nonhuman capital (such as equipment, structures, intellectual property, or financial assets), or human capital (such as training, education, experience, and skills). Like other forms of capital, human capital is an asset that can generate a stream of income. A well-trained plumber can earn more each year than an unskilled worker, even if they both work the same number of hours. The third group of winners is made up of the superstars among us who have special talents – or luck. (pages 133-134)

The most basic economic model, write Brynjolfsson and McAfee, treats technology as a simple multiplier on everything else, increasing overall productivity evenly for everyone. In other words, all labor is affected equally by technology. Every hour worked produces more value than before.

A slightly more complex model allows for the possibility that technology may not affect all inputs equally, but rather may be ‘biased’ toward some and against others. In particular, in recent years, technologies like payroll processing software, factory automation, computer-controlled machines, automated inventory control, and word processing have been deployed for routine work, substituting for workers in clerical tasks, on the factory floor, and doing rote information processing.

By contrast, technologies like big data and analytics, high-speed communications, and rapid prototyping have augmented the contributions made by more abstract and data-driven reasoning, and in turn have increased the value of people with the right engineering, creative, and design skills. The net effect has been to decrease demand for less skilled labor while increasing the demand for skilled labor. Economists including David Autor, Lawrence Katz and Alan Krueger, Frank Levy and Richard Murnane, Daren Acemoglu, and many others have documented this trend in dozens of careful studies. They call it skill-biased technical change. By definition, skill-biased technical change favors people with more human capital. (page 135)

Skill-biased technical change can be seen in the growing income gaps between people with different levels of education.

Furthermore, organizational improvements related to technical advances may be even more significant than the technical advances themselves.

…Work that Erik did with Stanford’s Tim Bresnahan, Wharton’s Lorin Hitt, and MIT’s Shinkyu Yang found that companies used digital technologies to reorganize decision-making authority, incentives systems, information flows, hiring systems, and other aspects of their management and organizational processes. This coinvention of organization and technology not only significantly increased productivity but tended to require more educated workers and reduce demand for less-skilled workers. This reorganization of production affected those who worked directly with computers as well as workers who, at first glance, seemed to be far from the technology…

Among the industries in the study, each dollar of computer capital was often the catalyst for more than ten dollars of complementary investments in ‘organizational capital,’ or investments in training, hiring, and business process redesign. The reorganization often eliminates a lot of routine work, such as repetitive order entry, leaving behind a residual set of tasks that require relatively more judgment, skills, and training.

Companies with the biggest IT investments typically made the biggest organizational changes, usually with a lag of five to seven years before seeing the full performance benefits. These companies had the biggest increase in the demand for skilled work relative to unskilled work….

This means that the best way to use new technologies is usually not to make a literal substitution of a machine for each human worker, but to restructure the process. Nonetheless, some workers (usually the less skilled ones) are still eliminated from the production process and others are augmented (usually those with more education and training), with predictable effects on the wage structure. Compared to simply automating existing tasks, this kind of organizational coinvention requires more creativity on the part of entrepreneurs, managers, and workers, and for that reason it tends to take time to implement the changes after the initial invention and introduction of new technologies. But once the changes are in place, they generate the lion’s share of productivity improvements. (pages 137-138)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee explain that skill-biased technical change can be somewhat misleading in the context of jobs eliminated as companies have reorganized. It’s more accurate to say that routine tasks – whether cognitive or manual – have been replaced the most by computers. One study by Nir Jaimovich and Henry Siu found that the demand for routine cognitive tasks such as cashiers, mail clerks, and bank tellers and routine manual tasks such as machine operators, cement masons, and dressmakers was not only falling, but falling at accelerating rate.

These jobs fell by 5.6 percent between 1981 and 1991, 6.6 percent between 1991 and 2001, and 11 percent between 2001 and 2011. In contrast, both nonroutine cognitive work and nonroutine manual work grew in all three decades. (pages 139-140)

Since the early 1980s, when computers began to be adopted, the share of income going to labor has declined while the share of income going to owners of physical capital has increased. However, as new capital is added cheaply at the margin, the rewards earned by capitalists may not automatically grow relative to labor, observe the authors.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE BOUNTY AND THE SPREAD

Franklin D. Roosevelt:

The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have little.

Like productivity, state Brynjolfsson and McAfee, GDP, corporate investment, and after-tax profits are also at record highs. Yet the employment-to-population ratio is lower than at any time in at least two decades. This raises three questions:

- Will the bounty overcome the spread?

- Can technology not only increase inequality but also create structural unemployment?

- What about globalization, the other great force transforming the economy – could it explain recent declines in wages and employment?

Thanks to technology, we will keep getting ever more output from fewer inputs like raw materials, capital, and labor. We will benefit from higher productivity, but also from free digital goods. Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

… ‘Bounty’ doesn’t simply mean more cheap consumer goods and empty calories. As we noted in chapter 7, it also means simultaneously more choice, greater variety, and higher quality in many areas of our lives. It means heart surgeries performed without cracking the sternum and opening the chest cavity. It means constant access to the world’s best teachers combined with personalized self-assessments that let students know how well they’re mastering the material. It means that households have to spend less of their total budget over time on groceries, cars, clothing, and utilities. It means returning hearing to the deaf and, eventually, sight to the blind. It means less need to work doing boring, repetitive tasks and more opportunity for creative, interactive work. (page 166)

However, technological progress is also creating ever larger differences in important areas – wealth, income, standards of living, and opportunities for advancement. If the bounty is large enough, do we need to worry about the spread? If all people’s economic lives are improving, then is increasing spread really a problem? Harvard economist Greg Mankiw has argued that the enormous income of the ‘one percent’ may reflect – in large part – the rewards of creating value for everyone else. Innovators improve the lives of many people, and the innovators often get rich as a result.

The high-tech industry offers many examples of this happy phenomenon in action. Entrepreneurs create devices, websites, apps, and other goods and services that we value. We buy and use them in large numbers, and the entrepreneurs enjoy great financial success…

We particularly want to encourage it because, as we saw in chapter 6, technological progress typically helps even the poorest people around the world. Careful research has shown that innovations like mobile telephones are improving people’s incomes, health, and other measures of well-being. As Moore’s Law continues to simultaneously drive down the cost and increase the capability of these devices, the benefits they bring will continue to add up. (pages 167-168)

Those who believe in the strong bounty argument think that unmeasured price decreases, quality improvements, and other benefits outweigh the lost ground in other areas, such as the decline in the median real income.

Unfortunately, however, some important items such as housing, health care, and college have gotten much more expensive over time. Brynjolfsson and McAfee cite research by economist Jared Bernstein, who found that while median family income grew by 20 percent between 1990 and 2008, prices for housing and college grew by about 50 percent, and health care by more than 150 percent. Moreover, median incomes have been falling in recent years.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee then add:

That many Americans face stagnant and falling income is bad enough, but it is now combined with decreasing social mobility – an ever lower chance that children born at the bottom end of the spread will escape their circumstances and move upward throughout their lives and careers… This is exactly what we’d expect to see as skill-biased technical changes accelerates. (pages 170-171)

Based on economic theory and supported by most of the past two hundred years, economists have generally agreed that technological progress has created more jobs than it has destroyed. Some workers are displaced by new technologies, but the increase in total output creates more than enough new jobs.

Regarding economic theory, there are three possible arguments: inelastic demand, rapid change, and severe inequality.

If lower costs leads to lower prices of goods, and if lower prices leads to increased demand for the goods, then this may lead to an increase in the demand for labor. It depends on the elasticity of demand.

For some goods, such as lighting, demand is relatively inelastic: price declines have not led to a proportionate increase in demand. For other goods, demand has been relatively elastic: price declines have resulted in an even greater increase in demand. One example, write Brynjolfsson and McAfee, is the Jevons paradox: more energy efficiency can sometimes lead to greater total demand for energy.

If elasticity is exactly equal to one – so a 1 percent decline in price leads to a 1 percent increase in demand – then total revenues (price times quantity) are unchanged, explain Brynjolfsson and McAfee. In this case, an increase in productivity, meaning less labor needed for each unit of output, will be exactly offset by an increase in total demand, so that the overall demand for labor is unchanged. Elasticity of one, it can be argued, is what happens in the overall economy.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee remark that the second, more serious, argument for technological unemployment is that our skills, organizations, and institutions cannot keep pace with technological change. What if it takes ten years for displaced workers to learn new skills? What if, by then, technology has changed again?

Faster technological progress may ultimately bring greater wealth and longer lifespans, but it also requires faster adjustments by both people and institutions. (page 178)

The third argument is that ongoing technological progress will lead to a continued decline in real wages for many workers. If there’s technological progress where only those with specific skills, or only those who own a certain kind of capital, benefit, then the equilibrium wage may indeed approach a dollar an hour or even zero. Over history, many inputs to production, from whale oil to horses, have reached a point where they were no longer needed even at zero price.

Although job growth has stopped tracking productivity upward in the past fifteen years or so, it’s hard to know what the future holds, say the authors.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee then ask: What if there were an endless supply of androids that never break down and that could do all the jobs that humans can do, but at essentially no cost? There would be an enormous increase in the volume, variety, and availability of goods.

But there would also be severe dislocations to the labor force. Entrepreneurs would continue to invent new products and services, but they would staff these companies with androids. The owners of androids and other capital assets or natural resources would capture all the value in the economy. Those with no assets would have only labor to sell, but it would be worthless. Brynjolfsson and McAfee sum it up: you don’t want to compete against close substitutes when those substitutes have a cost advantage.

But in principle, machines can have very different strengths and weaknesses than humans. When engineers work to amplify these differences, building on the areas where machines are strong and humans are weak, then the machines are more likely to complement humans rather than substitute for them. Effective production is more likely to require both human and machine inputs, and the value of the human inputs will grow, not shrink, as the power of the machines increases. A second lesson of economics and business strategy is that it’s great to be a complement to something that’s increasingly plentiful. Moreover, this approach is more likely to create opportunities to produce goods and services that could never have been created by unaugmented humans, or machines that simply mimicked people, for that matter. These new goods and services provide a path for productivity growth based on increased output rather than reduced inputs.

Thus in a very real sense, as long as there are unmet needs and wants in the world, unemployment is a loud warning that we simply aren’t thinking hard enough about what needs doing. We aren’t being creative enough about solving the problems we have using the freed-up time and energy of the people whose old jobs were automated away. We can do more to invent technologies and business models that augment and amplify the unique capabilities of humans to create new sources of value, instead of automating the ones that already exist. As we will discuss further in the next chapters, this is the real challenge facing our policy makers, our entrepreneurs, and each of us individually. (page 182)

LEARNING TO RACE WITH MACHINES: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INDIVIDUALS

Pablo Picasso on computers:

But they are useless. They can only give you answers.

Even where digital machines are far ahead of humans, humans still have important roles to play. IBM’s Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov in a chess match in 1997. And nowadays even cheap chess programs are better than any human. Does that mean humans no longer have anything to contribute to chess? Brynjolfsson and McAfee quote Kasparov’s comments on ‘freestyle’ chess (which involves teams of humans plus computers):

The teams of human plus machine dominated even the strongest computers. The chess machine Hydra, which is a chess-specific supercomputer like Deep Blue, was no match for a strong human player using a relatively weak laptop. Human strategic guidance combined with the tactical acuity of a computer was overwhelming.

The surprise came at the conclusion of the event. The winner was revealed to be not a grandmaster with a state-of-the-art PC but a pair of amateur American chess players using three computers at the same time. Their skill at manipulating and ‘coaching’ their computers to look very deeply into positions effectively counteracted the superior chess understanding of their grandmaster opponents and the greater computational power of other participants. Weak human + machine + better process was superior to a strong computer alone and, more remarkably superior to a strong human + machine + inferior process. (pages 189-190)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee explain:

The key insight from freestyle chess is that people and computers don’t approach the same task the same way. If they did, humans would have had nothing to add after Deep Blue beat Kasparov; the machine, having learned how to mimic human chess-playing ability, would just keep riding Moore’s Law and racing ahead. But instead we see that people still have a great deal to offer the game of chess at its highest levels once they’re allowed to race with machines, instead of purely against them.

Computers are not as good as people at being creative:

We’ve never seen a truly creative machine, or an entrepreneurial one, or an innovative one. We’ve seen software that could create lines of English text that rhymed, but none that could write a true poem… Programs that can write clean prose are amazing achievements, but we’ve not yet seen one that can figure out what to write about next. We’ve also never seen software that could create good software; so far, attempts at this have been abject failures.

These activities have one thing in common: ideation, or coming up with new ideas or concepts. To be more precise, we should probably say good new ideas or concepts, since computers can easily be programmed to generate new combinations of preexisting elements like words. This however, is not recombinant innovation in any meaningful sense. It’s closer to the digital equivalent of a hypothetical room full of monkeys banging away randomly on typewriters for a million years and still not reproducing a single play of Shakespeare’s.

Ideation in its many forms is an area today where humans have a comparative advantage over machines. Scientists come up with new hypotheses. Journalists sniff out a good story. Chefs add a new dish to the menu. Engineers on a factory floor figure out why a machine is no longer working properly. [Workers at Apple] figure out what kind of tablet computer we actually want. Many of these activities are supported or accelerated by computers, but none are driven by them.

Picasso’s quote at the head of this chapter is just about half right. Computers are not useless, but they’re still machines for generating answers, not posing interesting new questions. That ability still seems to be uniquely human, and still highly valuable. We predict that people who are good at idea creation will continue to have a comparative advantage over digital labor for some time to come, and will find themselves in demand. In other words, we believe that employers now and for some time to come will, when looking for talent, follow the advice attributed to the Enlightenment sage Voltaire: ‘Judge a man by his questions, not his answers.’

Ideation, innovation, and creativity are often described as ‘thinking outside the box,’ and this characterization indicates another large and reasonably sustainable advantage of human over digital labor. Computers and robots remain lousy at doing anything outside the frame of their programming… (pages 191-192)

Futurist Kevin Kelly:

You’ll be paid in the future based on how well you work with robots. (page 193)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee sum it up:

So ideation, large-frame pattern recognition, and the most complex forms of communication are cognitive areas where people still seem to have the advantage, and also seem likely to hold onto it for some time to come. Unfortunately, though, these skills are not emphasized in most educational environments today. (page 194)

Sociologists Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa have found in their research that many American college students today are not good at critical thinking, written communication, problem solving, and analytic reasoning. In other words, many college students are not good at ideation, pattern recognition, and complex communication. Arum and Roksa came to this conclusion after testing college students’ ability to read background documents and write an essay on them. A major reason for this shortcoming, say Arum and Roksa, is that college students spend only 9 percent of their time studying, while spending 51 percent of their time socializing, recreating, etc.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee emphasize that the future is uncertain:

We have to stress that none of our predictions and recommendations here should be treated as gospel. We don’t project that computers and robots are going to acquire the general skills of ideation, large-frame pattern recognition, and highly complex communication any time soon, and we don’t think that Moravec’s paradox is about to be fully solved. But one thing we’ve learned about digital progress is never say never. Like many other observers, we’ve been surprised over and over as digital technologies demonstrated skills and abilities straight out of science fiction.

In fact, the boundary between uniquely human creativity and machine capabilities continues to change. Returning to the game of chess, back in 1956, thirteen-year-old child prodigy Bobby Fischer made a pair of remarkably creative moves against grandmaster Donald Byrne. First he sacrificed his knight, seemingly for no gain, and then exposed his queen to capture. On the surface, these moves seemed insane, but several moves later, Fischer used these moves to win the game. His creativity was hailed at the time as the mark of genius. You today if you program that same position into a run-of-the-mill chess program, it will immediately suggest exactly the moves that Fischer played. It’s not because the computer has memorized the Fischer-Byrne game, but rather because it searches far enough ahead to see that these moves really do pay off. Sometimes, one man’s creativity is another machine’s brute-force analysis.

We’re confident that more surprises are in store. After spending time working with leading technologists and watching one bastion of human uniqueness after another fall before the inexorable onslaught of innovation, it’s becoming harder and harder to have confidence that any given task will be indefinitely resistant to automation. That means people will need to be more adaptable and flexible in their career aspirations, ready to move on from areas that become subject to automation, and seize new opportunities where machines complement and augment human capabilities. Maybe we’ll see a program that can scan the business landscape, spot an opportunity, and write up a business plan so good it’ll have venture capitalists ready to invest. Maybe we’ll see a computer that can write a thoughtful and insightful report on a complicated topic. Maybe we’ll see an automatic medical diagnostician with all the different kinds of knowledge and awareness of a human doctor. And maybe we’ll see a computer that can walk up the stairs to an elderly woman’s apartment, take her blood pressure, draw blood, and ask if she’s been taking her medication, all while putting her at ease instead of terrifying her. We don’t think any of these advances is likely to come any time soon, but we’ve also learned that it’s very easy to underestimate the power of digital, exponential, and combinatorial innovation. So never say never. (pages 202-204)

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Brynjolfsson and McAfee affirm that Economics 101 still applies because digital labor is still far from a complete substitute for human labor.

For now the best way to tackle our labor force challenges is to grow the economy. As companies see opportunity for growth, the great majority will need to hire people to seize them. Job growth will improve, and so will workers’ prospects. (page 207)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee also note that there is broad agreement among conservative and liberal economists when it comes to the government policies recommended by Economics 101.

(1) Education

The more educated the populace is, the more innovation tends to occur, which leads to more productivity growth and thus faster economic growth.

The educational system can be improved by using technology. Consider massive open online courses (MOOCs), which have two main economic benefits.

- The first and most obvious one is that MOOCs enable low-cost replication of the best teachers, content, and methods. Just as we can all listen to the best pop singer or cellist in the world today, students will soon have access to the most exciting geology demonstrations, the most insightful explanations of Renaissance art, and the most effective exercises for learning statistical techniques.

- The second, subtler benefit from the digitization of education is ultimately more important. Digital education creates an enormous stream of data that makes it possible to give feedback to both teacher and student. Educators can run controlled experiments on teaching methods and adopt a culture of continuous improvement. (pages 210-211)

Brynjolfsson and McAfee then add:

The real impact of MOOCs is mostly ahead of us, in scaling up the reach of the best teachers, in devising methods to increase the overall level of instruction, and in measuring and finding ways to accelerate student improvement… We can’t predict exactly which methods will be invented and which will catch on, but we do see a clear path for enormous progress. The enthusiasm and optimism in this space is infectious. Given the plethora of new technologies and techniques that are now being explored, it’s a certainty that some of them – in fact, we think many of them – will be significant improvements over current approaches to teaching and learning. (pages 211-212)

On the question of how to improve the educational system – in addition to using technology – it’s what you might expect: attract better teachers, lengthen school years, have longer school days, and implement a no-excuses philosophy that regularly tests students. Surprise, surprise: This is what has helped places like Singapore and South Korea to rank near the top in terms of education. Of course, while some teachers should focus on teaching testable skills, other teachers should be used to teach hard-to-measure skills like creativity and unstructured problem solving, observe Brynjolfsson and McAfee.

(2) Startups

Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

We champion entrepreneurship, but not because we think everyone can or should start a company. Instead, it’s because entrepreneurship is the best way to create jobs and opportunity. As old tasks get automated away, along with demand for their corresponding skills, the economy must invent new jobs and industries. Ambitious entrepreneurs are best at this, not well-meaning government leaders or visionary academics. Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Bill Gates, and many others created new industries that more than replaced the work that was eliminated as farming jobs vanished over the decades. The current transformation of the economy creates an equally large opportunity. (page 214)

Joseph Schumpeter argued that innovation is central to capitalism, and that it’s essentially a recombinant process. Schumpeter also held that innovation is more likely to take place in startups rather than in incumbent companies.

…Entrepreneurship, then, is an innovation engine. It’s also a prime source of job growth. In America, in fact, it appears to be the only thing that’s creating jobs. In a study published in 2010, Tim Kane of the Kauffman Foundation used Census Bureau data to divide all U.S. companies into two categories: brand-new startups and existing firms (those that had been around for at least a year). He found that for all but seven years between 1977 and 2005, existing firms as a group were net job destroyers, losing an average of approximately one million jobs annually. Startups, in sharp contrast, created on average a net three million jobs per year. (pages 214-215)

Entrepreneurship in America remains the best in the world, but it appears to have stagnated recently. One factor may be a decline in would-be immigrants. Immigrants have been involved in a high percentage of startups, but this trend appears to have slowed recently. Moreover, excessive regulation seems to be stymieing startups.

(3) Job Matching

It should be easier to match people with jobs. Better databases can be developed. So can better algorithms for identifying the needed skills. Ratings like TopCoder scores can provide objective metrics of candidate skills.

(4) Basic Science

Brynjolfsson and McAfee:

After rising for a quarter-century, U.S. federal government support for basic academic research started to fall in 2005. This is cause for concern because economics teaches that basic research has large beneficial externalities. This fact creates a role for government, and the payoff can be enormous. The Internet, to take one famous example, was born out of U.S. Defense Department research into how to build bomb-proof networks. GPS systems, touchscreen displays, voice recognition software like Apple’s Siri, and many other digital innovations also arose from basic research sponsored by the government. It’s pretty safe to say, in fact, that hardware, software, networks, and robots would not exist in anything like the volume, variety, and forms we know today without sustained government funding. This funding should be continued, and the recent dispiriting trend of reduced federal funding for basic research in America should be reduced. (pages 218-219)

For some scientific challenges, offering prizes can help: