July 10, 2022

Capitalism without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy, by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake, is an excellent book that everyone should read.

Historically most assets were tangible rather than intangible. Houses, castles, temples, churches, farms, farm animals, equipment, horses, weapons, jewels, precious metals, art, etc. These types of tangible assets tended to hold their value, and naturally they were included on accountants’ balance sheets.

Intangible assets are different. It’s harder to account for investing in intangibles. But intangible investment is important. Haskel and Westlake explain why:

Investment is what builds up capital, which, together with labor, constitutes the two measured inputs to production that power the economy, the sinews and joints that make the economy work. Gross domestic product is defined as the sum of the value of consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports; of these four, investment is often the driver of booms and recessions, as it tends to rise and fall in response to monetary policy and business confidence.

The problem is that national statistical offices have, until very recently, measured only tangible investments.

The Dark Matter of Investment

In 2002 in Washington, at a meeting of the Conference on Research in Income and Wealth, economists considered investments people made in the “new economy.” Carol Corrado and Dan Sichel of the US Federal Reserve Board and Charles Hulten of the University of Maryland developed a framework for thinking about different types of investments.

Haskel and Westlake mention Microsoft as an example. In 2006, Microsoft’s market value was about $250 billion. There was $70 billion in assets, $60 billion of which was cash and cash equivalents. Plant and equipment totaled only $3 billion, 4 percent of Microsoft’s assets and 1 percent of its market value. In a sense, Microsoft is a miracle: capitalism without capital.

Charles Hulten sought to explain Microsoft’s value by using intangible assets:

Examples include the ideas generated by Microsoft’s investments in R&D and product design, the value of its brands, its supply chains and internal structures, and the human capital built up by training.

Such intangible assets are similar to tangible assets in that the company had to spend time and money on them up-front, while the value to the company was delivered over time.

Why Intangible Investment is Different

Businesses change what they invest in all the time, so how is intangible investment different? Haskel and Westlake:

Our central argument in this book is that there is something fundamentally different about intangible investment, and that understanding the steady move to intangible investment helps us understand some of the key issues facing us today: innovation and growth, inequality, the role of management, and financial and policy reform.

We shall argue there are two big differences with intangible assets. First, most measurement conventions ignore them. There are some good reasons for this, but as intangibles have become more important, it means we are now trying to measure capitalism without counting all the capital. Second, the basic economic properties of intangibles make an intangible-rich economy behave differently from a tangible-rich one.

Outline for this blog post:

Part I The Rise of the Intangible Economy

- Capital’s Vanishing Act: The Rise of Intangible Investment

- How to Measure Intangible Investment

- What’s Different About Intangible Investment? The Four S’s of Intangibles

Part II The Consequences of the Rise of the Intangible Economy

- Intangibles, Investment, Productivity, and Secular Stagnation

- Intangibles and the Rise of Inequality

- Infrastructure for Intangibles, and Intangible Infrastructure

- The Challenge of Financing an Intangible Economy

- Competing, Managing, and Investing in the Intangible Economy

- Public Policy in an Intangible Economy: Five Hard Questions

Part I The Rise of the Intangible Economy

CAPITAL’S VANISHING ACT

Investment has changed:

The type of investment that has risen inexorably is intangible: investment in ideas, in knowledge, in aesthetic content, in software, in brands, in networks and relationships.

Investment, assets, and capital all have multiple meanings.

For investment, Haskel and Westlake stick with the internationally agreed upon definition as given by the UN’s System of National Accounts:

Investment is what happens when a producer either acquires a fixed asset or spends resources (money, effort, raw materials) to improve it.

An asset is an economic resource that is expected to provide a benefit over a period of time. A fixed asset is an asset that results from using up resources in the process of its production.

Spending resources: To be an investment, the business doing the investing has to acquire the asset or pay some cost to produce it themselves.

Haskel and Westlake offer some examples of intangible investments:

Suppose a solar panel manufacturer researches and discovers a cheaper process for making photovoltaic cells: it is incurring expense in the present to generate knowledge it expects to benefit from in the future. Or consider a streaming music start-up that spends months designing and negotiating deals with record labels to allow it to use songs the record labels own—again, short-term expenditure to create longer-term gain. Or imagine a training company pays for the long-term rights to run a popular psychometric test: it too is investing.

(Photo by magele-picture)

Intangible investing results in intangible assets. More examples of intangible investments:

- Software

- Databases

- R&D

- Mineral exploration

- Creating entertainment, literary or artistic originals

- Design

- Training

- Market research and branding

- Business process re-engineering

Intangible Investment Has Steadily Grown

Supermarkets have developed complex pricing systems, more ambitious branding and marketing campaigns, and more detailed processes and systems (including better use of bar codes). Moreover, as you might expect, tech firms make heavy use of intangible investments, as Haskel and Westlake explain:

Fast-growing tech companies are some of the most intangible-intensive of firms. This is in part because software and data are intangibles, and the growing power of computers and telecommunications is increasing the scope of things that software can achieve. But the process of “software eating the world,” in venture capitalist Marc Andreesen’s words, is not just about software: it involves other intangibles in abundance. Consider Apple’s designs and its unrivaled supply chain, which has helped it to bring elegant products to market quickly and in sufficient numbers to meet customer demand, or the networks of drivers and hosts that sharing-economy giants like Uber and AirBnB have developed, or Tesla’s manufacturing know-how. Computers and the Internet are important drivers of this change in investment, but the change is long running and predates not only the World Wide Web but even the Internet and the PC.

By the mid-1990s, intangible investment in the United States exceeded tangible investment. There is a similar pattern for the UK, Sweden, and Finland. But tangible investment is still greater than intangible investment in Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Denmark, and the Netherlands.

Reasons for the Growth of Intangible Investment

Because the productivity of the manufacturing sector typically increases faster than that of the services sector, labor-intensive services gradually become more expensive compared to manufactured goods. (This is called Baumol’s Cost Disease.) This implies that intangible investing will grow faster than tangible investing over time.

Furthermore, new technology seems to create greater opportunities for businesses to invest productively in intangibles. Haskel and Westlake give Uber as an example. It would have been possible before computers and smartphones for Uber to develop its large network of drivers. But smartphones—which connect people quickly, allow the rating of drivers, and make payment quick and easy—significantly boosted the return on investment for Uber.

It’s natural to wonder if computers are the cause of increased intangible investment. Haskel and Westlake suggest that while computers may be a primary cause, they do not seem to be the only cause:

First of all, as we saw earlier, the rise of intangible investment began before the semiconductor revolution, in the 1940s and 1950s and perhaps before. Second, while some intangibles like software and data strongly rely on computers, others do not: brands, organizational development, and training, for example. Finally, a number of writers in the innovation studies literature argue that it may be that it was the rise of intangibles that led to the development of modern IT as much as the other way around.

HOW TO MEASURE INTANGIBLE INVESTMENT

Productivity growth in the United States starting in the mid-1970s and throughout the 1980s seemed quite low. Economists found this puzzling because computers seemed to be making a difference in a variety of areas. Statistical agencies, led by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), made two adjustments:

First, in the 1980s, in conjunction with IBM, the BEA started to produce indexes of computer prices that were quality adjusted. This turned out to make a very big difference to measuring how much investment businesses were making in computer hardware.

In most cases—for products, for example—prices for the same good tend to rise gently in line with overall inflation. But even if sticker prices for computers were rising, they were decidedly not the same good, since every dimension of their quality (speed, memory, and space) was improving incredibly. So their “quality-adjusted” prices were, in fact, falling and falling very fast, meaning that the quality you could buy per dollar spent on computers was in fact rising very fast.

In the 1990s, statisticians looked at business spending that creates computer software. Haskel and Westlake comment that banks are huge spenders on the creation of software (at one point, Citibank employed more programmers than Microsoft). Software is an intangible good—knowledge written down in lines of code.

(Photo by Krisana Antharith)

By the early 2000s, many business economists realized that knowledge more generally is an intangible investment that should be included in GDP and productivity measures. Gradually statistical offices began to incorporate various intangible investments into GDP statistics. Haskel and Westlake:

And these changes added up. In the United States, for example, the capitalization of software added about 1.1 percent to 1999 US GDP and R&D added 2.5 percent to 2012 GDP, with these numbers growing all the time…

What Sorts of Intangibles Are There?

Corrado, Hulten, and Sichel divided intangible investment into three broad types:

- Computerized Information: Software development; Database development.

- Innovative Property: R&D; Mineral exploration; Creating entertainment and artistic originals; Design and other product development costs.

- Economic Competencies: Training; Market research and branding; Business process re-engineering.

Right now, design and other product development costs are not included in official GDP measures. Also not included: training, market research and branding, and business process re-engineering.

Measuring Investment in Intangibles

Haskel and Westlake:

Measuring investment requires a number of steps. First, we need to find out how much firms are spending on the intangible. Second, in some cases, not all of that spending will be creating a long-lived asset… So we may have to adjust that spending to measure investment—that is, that part of spending creating a long-lived asset. Third, we need to adjust that investment for inflation and quality change so we can compare investment in different periods when prices and quality are changing.

For most investment goods, national accountants simply send out a survey to companies asking them how much there are spending on each good. It’s trickier, however, if it’s an intangible good that the company makes for itself, like writing its own software or doing its own R&D. In this case, statisticians can figure out how much it costs a company—over and above wages—to produce the intangible good. Statisticians also must estimate how much of that additional spending is an investment that will last for more than a year. The third step is to adjust for inflation and quality changes.

To measure the intangible asset created by intangible investment, economists have to estimate depreciation. Once you know the flow of intangible investment and you adjust for depreciation, you can then estimate the stock—the value of intangible assets in a given year. For software, design, marketing, and training, depreciation is about 33 percent a year. For R&D, depreciation is roughly 15 percent a year. For entertainment and artistic originals and mineral exploration, depreciation is lower.

WHAT’S DIFFERENT ABOUT INTANGIBLE INVESTMENT?

An intangible-rich economy has four characteristics—the four S’s—that distinguish it from a tangible-rich economy. Intangible assets:

- Are more likely to be scalable;

- Their costs are more likely to be sunk;

- They are inclined to have spillovers;

- They tend to exhibit synergies with each other.

Scalability

Why Are Intangibles Scalable?

Scalability derives from what economists call “non-rivalry” goods. A rival good is like a loaf of bread. Once one person eats the loaf of bread, no one else can eat that loaf. In contrast, a non-rival good is not used up when one person uses it. For instance, once a software program has been created, it can be reproduced an infinite number of times at almost no cost. There’s virtually no limit to how many people can make use of that one software program. Another example, given by Paul Romer—a pioneer of how economists think about economic growth—is oral rehydration therapy (ORT). ORT is a simple treatment that has saved many lives in the developing world by stopping children’s deaths from diarrhea. The idea of ORT can be used again and again—it’s never used up.

Note: Scalability can really take off if there are “network effects.” Haskel and Westlake mention networks like Uber drivers or Instagram users as examples.

(Illustration by Aquir)

Why Does Scalability Matter?

Haskel and Westlake say that we will see three unusual things happening in an economy where more investments are clearly scalable:

- There will be some highly intangible-intensive businesses that have gotten very large. Google, Microsoft, and Facebook are good examples. Their software can be reproduced countless times at almost no cost.

- Given the prospects of such large markets, ever more firms feel incentivized to go for it.

- Businesses who compete with owners of scalable assets are in a tough position. In markets with hugely scalable assets, the rewards for runners-up are often meager.

Sunkenness

Why Are Intangibles Sunk Costs?

Intangible assets are much harder to sell than tangible assets. If an intangible investment works, creating value for the company that made the investment, then there’s no issue. However, if an intangible investment doesn’t work or the company wants to back out, it’s often hard to sell. Specifically, if knowledge isn’t protected by intellectual property rights, it’s often impossible to sell.

Why Does Sunkenness Matter?

Because intangible investments frequently involve unrecoverable costs, they can be difficult to finance, especially with debt. There’s a reason why many small business loans require a lien on directors’ houses: a house is a tangible asset with ascertainable value.

Moreover, people tend to fall for the sunk-cost fallacy, whereby they overvalue an intangible asset that hasn’t worked out because of the time, energy, and resources they’ve poured into it. People are inclined to continue putting in more time and resources. This may contribute to bubbles.

Spillovers

Why Do Intangibles Generate Spillovers?

Intangible investments can be used relatively easily by companies that didn’t make the investments. Consider R&D. Unless it is protected by patents, knowledge gained through R&D can be re-used again and again. Haskel and Westlake remark:

Patents and copyrights are, on the whole, less secure and more subject to challenge than the title deeds to farmland or the ownership of a shipping container or a computer.

One reason is that property rights related to tangible assets have been around for thousands of years.

Why Do Spillovers Matter?

(Photo by Vs1489)

Haskel and Westlake remark that spillovers matter for three reasons:

- First, in a world where companies can’t be sure they will obtain the benefits of their investments, we would expect them to invest less.

- Second, there is a premium on the ability to manage spillovers: companies that can make the most of their own investments in intangibles, or that are especially good at exploiting the spillovers from others’ investments, will do particularly well.

- Third, spillovers affect the geography of modern economies.

The U.S. government funds 30 percent of the R&D that happens in the country. It’s the classic answer to the issue of companies being unsure about the benefits of intangible investments they’re considering. Public R&D is particularly important for basic research.

Haskel and Westlake:

Patent trolls and copyright lawsuits catch our attention because they are newsworthy, but other ways of capturing the spillovers of intangible investment are common—in fact, they’re part of the invisible fabric of everyday business life. They often involve reciprocity rather than compulsion or legal threats. Software developers use online repositories like GitHub to share code; being an active contributor and an effective user of GitHub is a badge of honor for some developers. Firms sometimes pool their patents; they realize that the spillovers from each company’s technologies are valuable, and that enforcing everyone’s individual legal rights is not worth it. (Indeed, the US government helped end the patent war between the Wright Brothers and Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company that was holding back the US aircraft industry in the 1910s by getting everyone to set up a patent pool, the Manufacturers Aircraft Association.)

Synergies

Why Do Intangibles Exhibit Synergies?

Haskel and Westlake give the example of the microwave. Near the end of World War II, Raytheon was mass-producing cavity magnetrons (similar to a vacuum tube), a crucial part of the radar defenses the British had invented. A Raytheon engineer, Percy Spenser, realized the microwaves from magnetrons could heat food by creating electromagnetic fields in a box.

Haskel and Westlake write:

A few companies tried to sell domestic microwave ovens, but none were very successful. Then, in the 1960s, Raytheon bought Amana, a white goods manufacturer, and combined their microwave expertise with Amana’s kitchen appliance knowledge to build a more successful product. At the same time, Litton, another defense contractor, invented the modern microwave oven shape and tweaked the magnetron to make it safer.

In 1970 forty thousand microwaves were sold. By 1975 it was a million. What made this possible was the gradual accumulation of ideas and innovations. The magnetron on its own wasn’t very useful to a customer, but combined with other incremental bits of R&D and the design and marketing ideas of Litton and Amana, it became a defining innovation of the late twentieth century.

The point of the microwave story is that intangible assets have synergies with one another. Also, it’s hard to predict where innovations will come from or how they will combine. In this example, military technology led to a kitchen appliance.

(Synergies in digital business, science, and technology: Illustration by Agsandrew)

Intangible assets have synergies with tangible assets as well. In the 1990s, productivity increased and at first people didn’t know why. Haskel and Westlake explain:

In 2000 the McKinsey Global Institute analyzed the sources of this productivity increase. Counterintuitively, they found that the bulk of it came from the way big chains retailers, in particular Walmart, were using computers and software to reorganize their supply chains, improve efficiency, and lower prices. In a sense, it was a technological revolution. But the gains were realized through organizational and business practice changes in a low-tech sector. Or, to put it another way, there were big synergies between Walmart’s investment in computers and its investment in processes and supply chain development to make the most of the computers.

Why Do the Synergies of Intangible Assets Matter?

While spillovers cause firms to be protective of their intangible investments, synergies have the opposite effect and lead to open innovation.

In its simplest form, open innovation happens when a firm deliberately connects with and benefits from new ideas that arise outside the firm itself. Cooking up ideas in a big corporate R&D lab is not open innovation; getting ideas by buying start-ups, partnering with academic researchers, or undertaking joint ventures with other companies is.

(Illustration by mindscanner)

Besides open innovation, there’s a second reason why synergies matter:

They also matter because they create an alternative way for firms to protect their intangible investments against competition: by building synergistic clusters of intangible investments, rather than by protecting individual assets.

Part II The Consequences of the Rise of the Intangible Economy

INTANGIBLES, INVESTMENT, PRODUCTIVITY, AND SECULAR STAGNATION

Two characteristics of secular stagnation are low investment and low interest rates. Investment fell in the 1970s, recovered some in the mid-1980s, but fell sharply in the financial crisis (2008) and hasn’t recovered.

What’s puzzling is that investment hasn’t recovered despite low interest rates. In the past, central banks relied on lowering rates to spur investment activity. But that seems not to have worked this time.

One possible explanation is that technological progress has slowed. Robert Gordon makes this argument in The Rise and Fall of American Growth (2016). But technological progress is quite difficult to measure.

There are three more aspects to secular stagnation.

- Corporate profits in the United States are higher than they’ve been for decades, and they seem to keep increasing. Return on invested capital (ROIC) has grown significantly since the 1990s.

- When it comes to both profitability and productivity, there is a growing gap between leaders and laggards.

- Productivity growth has slowed due mostly to a decline in total factor productivity—workers are working less effectively with the capital they have.

Haskel and Westlake note that a good explanation for secular stagnation should explain four facts:

- A fall in measured investment at the same time as a fall in interest rates

- Strong profits

- Increasingly unequal productivity and profits

- Weak total factor productivity growth

Intangibles can help explain these facts.

Mismeasurement: Intangibles and Apparently Low Investment

Intangible investment exceeds tangible investment in countries including the United States and the UK. Are economies growing faster than reported because the value of intangibles is not being properly measured? Haskel and Westlake show that including intangibles does not noticeably change investment/GDP.

Profits and Productivity Differences: Scale, Spillovers, and the Incentives to Invest

Haskel and Westlake state:

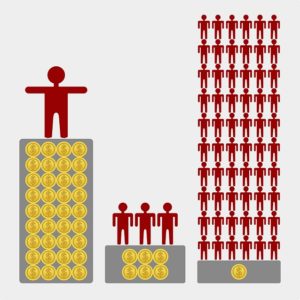

…leading firms, which are confident of their ability to create scalable assets and to appropriate most of their benefits, will continue to invest (and enjoy a high rate of return on those investments); but laggard firms, expecting low private returns from their investments, will not. In a world where there are a few leaders and many laggards, the net effect of this could be lower aggregate rates of investment, combined with high returns on those investments that do get made.

Spillovers: Intangibles and Slowing TFP Growth A Lower Pace of Intangible Growth?

The slowdown in intangible investment since the financial crisis does seem to account for slowing TFP (Total Factor Productivity) growth, although the data are noisy and more exploration is needed.

Are Intangibles Generating Fewer Spillovers?

Lagging firms may be less able to absorb spillovers from leaders, possibly because leading firms can gain from synergies between different intangibles to a much greater extent than laggards.

INTANGIBLES AND THE RISE OF INEQUALITY

In addition to inequality of income and inequality of wealth, there is also what Haskel and Westlake call “inequality of esteem.” Some communities feel left-behind and overlooked by America’s prosperous coastal cities.

Standard explanations for inequality

One standard explanation for inequality is that new technologies replace workers, which causes wages to fall and profits to rise.

A second explanation relates to trade. In the 1980s, before the collapse of the Soviet Union and before market reforms in China and India, the global economy had 1.46 billion workers. Then in the 1990s, the number of workers doubled to 2.93 billion workers. This puts pressure on lower-skilled workers in developed economies. The flip side is that lower-skilled workers in China and India end up far better off than they were before.

A third explanation for inequality is that capital tends to accumulate. Capital tends to grow faster than the economy—this is Thomas Piketty’s famous r > g inequality—which causes capital to build up over time.

(Illustration by manakil)

How Intangibles Affect Income, Wealth, and Esteem Inequality

Intangibles, Firms, and Income Inequality

The best firms—owning scalable intangibles and able to extract spillovers from other businesses—will be highly productive and profitable while their competitors will lose out. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the best firms pays all their workers more. To explain rising wage inequality, more is needed.

Who is Benefiting from Intangible-Based Firm Inequality?

“Superstars” benefit by being associated with exceptionally valuable intangibles that can scale massively. Whereas in most markets a top worker could probably be replaced by two not-as-fast workers, this isn’t true for superstar markets: you can’t replace the best opera singer or the best basketball player with two not-quite-as-good ones. Tech billionaires also tend to be superstars with large equity stakes in companies they founded—companies that probably scaled massively.

However, senior managers have also done very well. Haskel and Westlake explain why:

Intangible investment increases. Because of its scalability and the benefits to companies that can appropriate intangible spillovers, leading companies pull ahead of laggards in terms of productivity, especially in the more intangible-intensive industries. The employees of these highly productive companies benefit from higher wages. Because intangibles are contestable, companies are especially eager to hire people who are good at contesting them—appropriating spillovers from other firms or identifying and maximizing synergies.

Why are CEOs at many companies being paid so much more than other workers? One reason relates to a “fundamental attribution error” whereby people explain a good business outcome by referring to what is simple and salient—like the skill of the CEO—rather than by acknowledging complexity and the fact that luck typically plays a major role. It’s also possible, say Haskel and Westlake, that shareholders—especially those who are most diversified—are not paying much attention to CEO pay.

Housing Prices, Cities, Intangibles, and Wealth Inequality

Intangibles can help explain wealth inequality. First, intangibles tend to drive up property prices. Second, the mobility of intangible capital means it’s harder to tax.

In a world where intangibles are becoming more abundant and a more important part of the way businesses create value, the benefits to exploiting spillovers and synergies increase. And as these benefits increase, we would expect businesses and their employees to want to locate in diverse, growing cities where synergies and spillovers abound.

Haskel and Westlake summarize how intangibles impact long-run inequality:

- First, inequality of income. The synergies and spillovers that intangibles create increase inequality between competing companies, and this inequality leads to increasing differences in employee pay… In addition, managing intangibles requires particular skills and education, and people with these skills are clustering in high-paid jobs in intangible-intensive firms. Finally, the growing economic importance of the kind of people who manage intangibles helps foster myths that can be used to justify excessive pay, especially for top managers.

- Second, inequality of wealth. Thriving cities are places where spillovers and synergies abound. The rise of intangibles makes cities increasingly attractive places to be, driving up the prices of prime property. This type of inflation has been shown to be one of the major causes of the increase in the wealth of the richest. In addition, intangibles are often mobile; they can be shifted across firms and borders. This makes capital more mobile, which makes it harder to tax. Since capital is disproportionately owned by the rich, this makes redistributive taxation to reduce wealth inequality harder.

- Finally, inequality of esteem. There is some evidence that supporters of populist movements… are more likely to hold traditional views and to score low on tests for the psychological trait of openness to experience.

INFRASTRUCTURE FOR INTANGIBLES, AND INTANGIBLE INFRASTRUCTURE

On the one hand, in order to thrive, the intangible economy needs new buildings in and around cities. On the other hand, artistic and creative institutions are important for combinatorial innovation. In the longer term, face-to-face interaction may eventually be phased out, but often these kinds of changes can take much longer than initially supposed.

(Illustration by Panimoni)

Haskel and Westlake comment:

The death of distance has failed to take place. Indeed, the importance of spillovers and synergies has increased the importance of places where people come together to share ideas and the importance of the transport and social spaces that make cities work.

But the death of distance may have been postponed rather than cancelled. Information technologies are slowly, gradually, replacing some aspects of face-to-face interaction. This may be a slow-motion change, like the electrification of factories—if so, the importance of physical infrastructure will radically change.

Soft infrastructure will also matter increasingly. The synergies between intangibles increase the importance of standards and norms, which together make up a kind of social infrastructure for intangible investment. And standards and norms are underpinned by trust and social capital, which are particularly important in an intangible economy.

THE CHALLENGE OF FINANCING AN INTANGIBLE ECONOMY

Banks are often criticized for not providing enough capital for businesses to succeed. Equity markets are criticized for being too short-term and also too influential. Managers seem to fixate more and more on shorter term stock prices. Managers may cut R&D to try to please short-term investors. Haskel and Westlake remark:

These concerns drive public policy across the developed world: most governments to some extent subsidize or coerce banks to lend to businesses, and they give tax advantages to companies that finance using debt. Many countries are considering measures to make equity investors take a longer-term perspective, such as imposing taxes on short-term shareholdings or changing financial reporting requirements. And most governments have spent money trying to encourage alternative forms of financing, particularly venture capital (VC), which is regarded as providing a big potential source of business growth and national wealth.

Banking: The Problem of Lending in a World of Intangibles

When a bank lends money to a business, the bank usually has some recourse to the assets of the business if the debt isn’t repaid. However, intangible assets are typically much harder to value than tangible assets, and frequently intangible assets don’t have much value at all when a business fails. Thus it is difficult for a bank to lend to a business whose assets are mostly intangible.

This is why industries with mostly tangible assets—like oil and gas producers—have high leverage (are funded more with debt than equity), while industries with mostly intangible assets—like software—have less debt and more equity.

One way to increase bank lending to businesses with more intangible assets is for the government to cofund or guarantee bank loans. A second way is financial innovation, such as finding ways to value intangible assets—like patents—more accurately. A third way to deal with the issue of lending against intangibles is to get businesses to rely more on equity than debt.

Haskel and Westlake on how equity markets impact intangible investing:

There is some evidence that markets are short-termist, to the extent that management can sometimes boost their company’s share price by cutting intangible investment to preserve or increase profits, or cut investment to buy back stock. But it also seems that some of what is happening is a sharpening of managerial incentives: publicly held companies whose managers own stock focus on types of intangible investment that are more likely to be successful. And the extent of market myopia varies: companies with more concentrated, sophisticated investors are less likely to feel pressure to cut intangible investment than those with dispersed, unsophisticated ones.

Why VC Works for Intangibles

(Photo by designer491)

Haskel and Westlake observe:

VC has several characteristics that make it especially well-suited to intangible-intensive businesses: VC firms take equity stakes, not debt, because intangible-rich businesses are unlikely to be worth much if they fail—all those sunk investments. Similarly, to satisfy their own investors, VC funds rely on home-run successes, made possible by the scalability of assets like Google’s algorithms, Uber’s driver network, or Genentech’s patents. Third, VC is often sequential, with rounds of funding proceeding in stages. This is a response to the inherent uncertainty of intangible investment.

Leading VC firms and their partners are well-connected and credible, which helps in building networks to exploit synergies.

COMPETING, MANAGING, AND INVESTING IN THE INTANGIBLE ECONOMY

Businesses look to improve their performance in a way that is sustainable. How can this be done? The advice has always been to build and maintain distinctive assets. Tangible assets are usually not distinctive, or at least not for long. Haskel and Westlake:

It’s much more likely that the types of intangible assets we have talked about in this book are going to be distinctive: reputation, product design, trained employees providing customer service. Indeed, perhaps the most distinctive asset will be the ability to weave all these assets together; so a particularly valuable intangible asset will be the organization itself.

When it comes to management, Haskel and Westlake suggest replacing the question, “What are managers for?” with a deeper question, “What’s the role of authority in an economy?”

Markets work with minimal government interference. However, firms can do a better job than dispersed individuals at organizing certain activities. Managers are people at firms who have authority. This is usually more efficient: managers tell employees what to do rather than discussing or arguing about every step.

But if management is largely just monitoring, and software can do the job of monitoring, then what is the role of managers in an intangible-intensive economy? For one, note Haskel and Westlake, the stakes tend to be much higher in the intangible economy. Moreover, in synergistic firms, only managers may understand the big picture.

How can managers build a good organization in an intangible-intensive firm? Haskel and Westlake explain:

…if you are primarily a producer of intangible assets (writing software, doing design, producing research) you probably want to build an organization that allows information to flow, helps serendipitous interactions, and keeps the key talent. That probably means allowing more autonomy, fewer targets, and more access to the boss, even if that is at the cost of influence activities.

Leadership is important in an intangible economy.

(Photo by Raywoo)

Having voluntary followers is really useful in an intangible economy. A follower will stay loyal to the firm, which keeps the tacit intangible capital at the firm. Better, if they are inspired by and empathize with the leader, they will cooperate with each other and feed information up to the leader. This is why leadership is going to be so valued in an intangible economy. It can at best replace, and likely mitigate, the costly and possibly distortive aspects of managing by authority.

Investing

How can an investor discern if a business is building intangible assets? Can investors learn about intangibles from accounting data?

Accountants try to match revenues with costs. If the company has a long-lived asset that produces revenues, then the company measures the annual cost by depreciation or amortization of that asset.

The other way to measure the cost of a long-lived asset is to expense the entire cost of creating the asset in the year in which the expenditures are made. However, this can lead to distortions. First, the costs in creating the asset can make profits in that year appear unusually low. By the same logic, if the asset in question continues producing revenues, then in future years profits will appear unusually high.

In the case of intangible assets, if the asset is bought from outside the company, then it is capitalized (and annual expenses are calculated based on depreciation or amortization). If the asset is created within the company, then the costs are recognized when they are spent (even if the asset is long-lived).

The result is that much intangible investment is hidden because it is expensed. This is a challenge for investors because economies are coming to rely increasingly on intangible assets. Book value—which is frequently based largely on tangible assets—is less relevant for a company that relies on intangible assets—especially if the company develops those assets internally.

What Should Investors Do?

The simplest solution for investors is to invest in low-cost broad market index funds. In this way, the investor will benefit from companies that rely on intangible assets.

Because index funds outpace 90-95% of all active investors if you measure performance over several decades, it already makes excellent sense for many investors to invest in index funds.

Haskel and Westlake sum up the chapter:

The growth of intangible investment has significant implications for managers, but it will affect different firms in different ways. Firms that produce intangible assets will want to maximize synergies, create opportunities to learn from the ideas of others (and appropriate the spillovers from others’ intangibles), and retain talent. These workplaces may end up looking rather like the popular image of hip knowledge-based companies. But companies that rely on exploiting existing intangible assets may look very different, especially where the intangible assets are organizational structure and processes. These may be much more controlled environments—Amazon’s warehouses rather than its headquarters. Leadership will be increasingly prized, to the extent that it allows firms to coordinate intangible investments in different areas and exploit their synergies.

Financial investors who can understand the complexity of intangible-rich firms will also do well. The greater uncertainty of intangible assets and the decreasing usefulness of company accounts put a premium on good equity research and on insight into firm management.

PUBLIC POLICY IN AN INTANGIBLE ECONOMY: FIVE HARD QUESTIONS

Haskel and Westlake highlight five of the most important challenges in an intangible-rich economy:

- First, intangibles tend to be contested: it is hard to prove who owns them, and even then their benefits have a tendency to spill over to others. Good intellectual property frameworks are important for an economy increasingly dependent on intangibles.

- Second, in an intangible economy, synergies are very important. Combining different ideas and intangible assets is central to successful business innovation. An important objective for policy makers is to create conditions for ideas to come together.

- The third challenge relates to finance and investment. Businesses and financial markets seem to underinvest in scalable, sunk intangible investments with a tendency to generate spillovers and synergies. The current system of business finance exacerbates the problem. A thriving intangible economy will significantly improve its financial system to make it easier for companies to invest in intangibles.

- Fourth, it will probably be harder for most businesses to appropriate the benefits of capital investment in the economies of the future than in the tangible-rich economies we are familiar with. Successful intangible-rich economies will have higher levels of public investment in intangibles.

- Fifth, governments must work out how to deal with the dilemma of the particular type of inequality that intangibles seem to encourage.

Clearer Rules and Norms about the Ownership of Intangibles

Stronger IP rights are not necessarily best because while they can increase incentive to invest, productivity gains are lowered. Also, strengthening IP rights might accidentally favor incumbent rights-holders and patent trolls.

Clearer IP rights can be helpful, though. They can reduce lawsuits that often end up in the notoriously troll-friendly Eastern District of Texas court.

Moreover, since intangible assets are often much more difficult to value than tangible assets, there are ways to help with this. For instance, Ian Hargreaves in 2011 suggested that the UK have a Digital Copyright Exchange. Another example is patent pools where firms coinvest in research and agree to share the resulting rights.

Helping Ideas Combine: Maximizing the Benefits of Synergies

Good public policy should be just as assiduous about creating the conditions for knowledge to spread, mingle, and fructify as it is about creating property rights for those who invest in intangibles.

It should be easy to build new workplaces and homes in cities. But simultaneously, cities have to be connected and livable.

A Financial Architecture for Intangible Investment

Governments should encourage new forms of debt that facilitate the ability to borrow against intangible assets. Longer term, governments should help a shift from debt to equity financing. Currently, debt is cheaper than equity due to the tax benefits of debt. This must change, but it will be very difficult because vested interests still rely on debt. Furthermore, new institutions will be required that provide equity financing to small and medium-size businesses. Although these shifts will be challenging, the rewards will be ever greater, note Haskel and Westlake.

Solving the Intangible Investment Gap

Some large firms seem able to gain from both their own intangible investments and from intangible investments made by others. These companies—like Google or Facebook—can be expected to continue making intangible investments.

Outside of these companies, the government and other public interest bodies (like large non-profit foundations) must make intangible investments.

The government is the investor of last resort. Here are three practical tips given by Haskel and Westlake for government investment in intangibles:

- Public R&D Funding. This means the government spending more on university research, public research institutes, or research undertaken by businesses. This type of government spending is not at all ideologically controversial and it can help a great deal over time.

- Public Procurement. When the US military funded the development of the semiconductor industry in the 1950s, they also acted as a lead customer. This helped Texas Instruments and other firms not just to invest in R&D, but also to build the capacity to produce and sell chips.

- Training and Education. Because it’s hard to predict what skills will be needed in 20 to 30 years, adult education may be a good area in which to invest. This could also help with inequality to some extent.

BOOLE MICROCAP FUND

An equal weighted group of micro caps generally far outperforms an equal weighted (or cap-weighted) group of larger stocks over time. See the historical chart here: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

This outperformance increases significantly by focusing on cheap micro caps. Performance can be further boosted by isolating cheap microcap companies that show improving fundamentals. We rank microcap stocks based on these and similar criteria.

There are roughly 10-20 positions in the portfolio. The size of each position is determined by its rank. Typically the largest position is 15-20% (at cost), while the average position is 8-10% (at cost). Positions are held for 3 to 5 years unless a stock approaches intrinsic value sooner or an error has been discovered.

The mission of the Boole Fund is to outperform the S&P 500 Index by at least 5% per year (net of fees) over 5-year periods. We also aim to outpace the Russell Microcap Index by at least 2% per year (net). The Boole Fund has low fees.

If you are interested in finding out more, please e-mail me or leave a comment.

My e-mail: jb@boolefund.com

Disclosures: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this article may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of Boole Capital, LLC.