If we’re more aware of cognitive biases today than a decade or two ago, that’s thanks in large part to the research of the Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. I’ve written about cognitive biases before, including:

- Cognitive Biases:https://boolefund.com/cognitive-biases/

- The Psychology of Misjudgment:https://boolefund.com/the-psychology-of-misjudgment/

I’ve seen few books that do a good job covering the work of Kahneman and Tversky.The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds, by Michael Lewis, is one such book. (Lewis also writes well about the personal stories of Kahneman and Tversky.)

Why are cognitive biases important? Economists, decision theorists, and others used to assume that people are rational. Sure, people make mistakes. But many scientists believed that mistakes are random: if some people happen to make mistakes in one direction–estimates that are too high–other people will (on average) make mistakes in the other direction–estimates that are too low. Since the mistakes are random, they cancel out, and so the aggregate results in a given market will nevertheless be rational. Markets are efficient.

For some markets, this is still true. Francis Galton, the English Victorian-era polymath, wrote about a contest in which 787 people guessed at the weight of a large ox. Most participants in the contest were not experts by any means, but ordinary people. The ox actually weighed 1,198 pounds. The average guess of the 787 guessers was 1,197 pounds, which was more accurate than the guesses made by the smartest and the most expert guessers. The errors are completely random, and so they cancel out.

This type of experiment can easily be repeated. For example, take a jar filled with pennies, where only you know how many pennies are in the jar. Pass the jar around in a group of people and ask each person–independently (with no discussion)–to write down their guess of how many pennies are in the jar. In a group that is large enough, you will nearly always discover that the average guess is better than any individual guess. (That’s been the result when I’ve performed this experiment in classes I’ve taught.)

However, in other areas, people do not make random errors, but systematic errors. This is what Kahneman and Tversky proved using carefully constructed experiments that have been repeated countless times. In certain situations, many people will tend to make mistakes in the same direction–these mistakes do not cancel out. This means that the aggregate results in a given market can sometimes be much less than fully rational. Markets can be inefficient.

Outline (based on chapters from Lewis’s book):

- Introduction

- Man Boobs

- The Outsider

- The Insider

- Errors

- The Collision

- The Mind’s Rules

- The Rules of Prediction

- Going Viral

- Birth of the Warrior Psychologist

- The Isolation Effect

- This Cloud of Possibility

(Illustration by Alain Lacroix)

INTRODUCTION

In his 2003 book,Moneyball, Lewis writes about the Oakland Athletic’s efforts to find betters methods for valuing players and evaluating strategies. By using statistical techniques, the team was able to perform better than many others teams even though the A’s had less money. Lewis says:

A lot of people saw in Oakland’s approach to building a baseball team a more general lesson: If the highly paid, publicly scrutinized employees of a business that had existed since the 1860s could be misunderstood by their market, what couldn’t be? If the market for baseball players was inefficient, what market couldn’t be? If a fresh analytical approach had led to the discovery of new knowledge in baseball, was there any sphere of human activity in which it might not do the same?

After the publication ofMoneyball, people started applying statistical techniques to other areas, such as education, movies, golf, farming, book publishing, presidential campaigns, and government. However, Lewis hadn’t asked the question of what it was about the human mind that led experts to be wrong so often. Why were simple statistical techniques so often better than experts?

The answer had to do with the structure of the human mind. Lewis:

Where do the biases come from? Why do people have them? I’d set out to tell a story about the way markets worked, or failed to work, especially when they were valuing people. But buried somewhere inside it was another story, one that I’d left unexplored and untold, about the way the human mind worked, or failed to work, when it was forming judgments and making decisions. When faced with uncertainty–about investments or people or anything else–how did it arrive at its conclusions? How did it process evidence–from a baseball game, an earnings report, a trial, a medical examination, or a speed date? What were people’s minds doing–even the minds of supposed experts–that led them to the misjudgments that could be exploited for profit by others, who ignored the experts and relied on data?

MAN BOOBS

Daryl Morey, the general manager of the Houston Rockets, used statistical methods to make decisions, especially when it came to picking players for the team. Lewis:

His job was to replace one form of decision making, which relied upon the intuition of basketball experts, with another, which relied mainly on the analysis of data. He had no serious basketball-playing experience and no interest in passing himself off as a jock or basketball insider. He’d always been just the way he was, a person who was happier counting than feeling his way through life. As a kid he’d cultivated an interest in using data to make predictions until it became a ruling obsession.

Lewis continues:

If he could predict the future performance of professional athletes, he could build winning sports teams… well, that’s where Daryl Morey’s mind came to rest. All he wanted to do in life was build winning sports teams.

Morey found it difficult to get a job for a professional sports franchise. He concluded that he’d have to get rich so that he could buy a team and run it. Morey got an MBA, and then got a job consulting. One important lesson Morey picked up was that part of a consultant’s job was to pretend to be totally certain about uncertain things.

There were a great many interesting questions in the world to which the only honest answer was, ‘It’s impossible to know for sure.’… That didn’t mean you gave up trying to find an answer; you just couched that answer in probabilistic terms.

Leslie Alexander, the owner of the Houston Rockets, had gotten disillusioned with the gut instincts of the team’s basketball experts. That’s what led him to hire Morey.

Morey built a statistical model for predicting the future performance of basketball players.

A model allowed you to explore the attributes in an amateur basketball player that led to professional success, and determine how much weight should be given to each.

The central idea was that the model would usually give you a “better” answer than relying only on expert intuition. That said, the model had to be monitored closely because sometimes it wouldn’t have important information. For instance, a player might have had a serious injury right before the NBA draft.

(Illustration by fotomek)

Statistical and algorithmic approaches to decision making are more widespread now. But back in 2006 when Morey got started, such an approach was not at all obvious.

In 2008, when the Rocket’s had the 33rd pick, Morey’s model led him to select Joey Dorsey. Dorsey ended up not doing well at all. Meanwhile, Morey’s model had passed over DeAndre Jordan, who ended up being chosen 35th by the Los Angeles Clippers. DeAndre Jordan ended up being the second best player in the entire draft, after Russell Westbrook. What had gone wrong? Lewis comments:

This sort of thing happened every year to some NBA team, and usually to all of them. Every year there were great players the scouts missed, and every year highly regarded players went bust. Morey didn’t think his model was perfect, but he also couldn’t believe that it could be so drastically wrong.

Morey went back to the data and ended up improving his model. For example, the improved model assigned greater weight to games played against strong opponents than against weak ones. Lewis adds:

In the end, he decided that the Rockets needed to reduce to data, and subject to analysis, a lot of stuff that had never before been seriously analyzed: physical traits. They needed to know not just how high a player jumped but how quickly he left the earth–how fast his muscles took him into the air. They needed to measure not just the speed of the player but the quickness of his first two steps.

At the same time, Morey realized he had to listen to his basketball experts. Morey focused on developing a process that relied both on the model and on human experts. It was a matter of learning the strengths and weaknesses of the model, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of human experts.

But it wasn’t easy. By letting human intuition play a role, that opened the door to more human mistakes. In 2007, Morey’s model highly valued the player Marc Gasol. But the scouts had seen a photo of Gasol without a shirt. Gasol was pudgy with jiggly pecs. The Rockets staff nicknamed Gasol “Man Boobs.” Morey allowed this ridicule of Gasol’s body to cause him to ignore his statistical model. The Rockets didn’t select Gasol. The Los Angeles Lakers picked him 48th. Gasol went on to be a two-time NBA All-Star. From that point forward, Morey banned nicknames because they could interfere with good decision making.

Over time, Morey developed a list of biases that could distort human judgment: confirmation bias, the endowment effect, present bias, hindsight bias, et cetera.

THE OUTSIDER

Although Danny Kahneman had frequently delivered a semester of lectures from his head, without any notes, he nonetheless always doubted his own memory. This tendency to doubt his own mind may have been central to his scientific discoveries in psychology.

But there was one experience he had while a kid that he clearly remembered. In Paris, about a year after the Germans occupied the city, new laws required Jews to wear the Star of David. Danny didn’t like this, so he wore his sweater inside out. One evening while going home, he saw a German soldier with a black SS uniform. The soldier had noticed Danny and picked him up and hugged him. The soldier spoke in German, with great emotion. Then he put Danny down, showed him a picture of a boy, and gave him some money. Danny remarks:

I went home more certain than ever that my mother was right: people were endlessly complicated and interesting.

Another thing Danny remembers is when his father came home after being in a concentration camp. Danny and his mother had gone shopping, and his father was there when they returned. Despite the fact that he was extremely thin–only ninety-nine pounds–Danny’s father had waited for them to arrive home before eating anything. This impressed Danny. A few years later, his father got sick and died. Danny was angry.

Over time, Danny grew even more fascinated by people–why they thought and behaved as they did.

When Danny was thirteen years old, he moved with his mother and sister to Jerusalem. Although it was dangerous–a bullet went through Danny’s bedroom–it seemed better because they felt they were fighting rather than being hunted.

On May 14, 1948, Israel declared itself a sovereign state. The British soldiers immediately left. The armies from Jordan, Syria, and Egypt–along with soldiers from Iraq and Lebanon–attacked. The war of independence took ten months.

Because he was identified as intellectually gifted, Danny was permitted to go to university at age seventeen to study psychology. Most of his professors were European refugees, people with interesting stories.

Danny wasn’t interested in Freud or in behaviorism. He wanted objectivity.

The school of psychological thought that most charmed him was Gestalt psychology. Led by German Jews–its origins were in the early twentieth century Berlin–it sought to explore, scientifically, the mysteries of the human mind. The Gestalt psychologists had made careers uncovering interesting phenomena and demonstrating them with great flair: a light appeared brighter when it appeared from total darkness; the color gray looked green when it was surrounded by violet and yellow if surrounded by blue; if you said to a person, “Don’t step on the banana eel!,” he’d be sure that you had said not “eel” but “peel.” The Gestalists showed that there was no obvious relationship between any external stimulus and the sensation it created in people, as the mind intervened in many curious ways.

(Two faces or a vase? Illustration by Peter Hermes Furian)

Lewis continues:

The central question posed by Gestalt psychologists was the question behaviorists had elected to ignore: How does the brain create meaning? How does it turn the fragments collected by the senses into a coherent picture of reality? Why does the picture so often seem to be imposed by the mind upon the world around it, rather than by the world upon the mind? How does a person turn the shards of memory into a coherent life story? Why does a person’s understanding of what he sees change with the context in which he sees it?

In his second year at Hebrew Univeristy, Danny heard a fascinating talk by a German neurosurgeon. This led Danny to abandon psychology in order to pursue a medical degree. He wanted to study the brain. But one of his professors convinced him it was only worth getting a medical degree if he wanted to be a doctor.

After getting a degree in psychology, Danny had to serve in the Israeli military. The army assigned him to the psychology unit, since he wasn’t really cut out for combat. The head of the unit at that time was a chemist.Danny was the first psychologist to join.

Danny was put in charge of evaluating conscripts and assigning them to various roles in the army. Those applying to become officers had to perform a task: to move themselves over a wall without touching it using only a log that could not touch the wall or the ground. Danny and his coworkers thought that they could see “each man’s true nature.” However, when Danny checked how the various soldiers later performed, he learned that his unit’s evaluations–with associated predictions–were worthless.

Danny compared his unit’s delusions to theM¼ller-Lyer optical illusion. Are these two lines the same length?

(M¼ller-Lyer optical illusion by Gwestheimer, Wikimedia Commons)

The eye automatically sees one line as longer than the other even though the lines have equal length. Even after you use a ruler to show the lines are equal, the illusion persists. If we’re automatically fooled in such a simple case, what about in more complex cases?

Danny thought up a list of traits that seemed correlated with fitness for combat. However, Danny was concerned about how to get an accurate measure of these traits from an interview. One problem was the halo effect: If people see that a person is strong, they tend to see him as impressive in other ways. Or if people see a person as good in certain areas, then they tend to assume that he must be good in other areas. More on the halo effect:https://boolefund.com/youre-deluding-yourself/

Danny developed special instructions for the interviewers. They had to ask specific questions not about how subjects thought of themselves, but rather about how they actually had behaved in the past. Using this information, before moving to the next question, the interviewers would rate the subject from 1 to 5. Danny’s essential process is still used in Israel today.

THE INSIDER

To his fellow Israelis, Amos Tversky somehow was, at once, the most extraordinary person they had ever met and the quintessential Israeli. His parents were among the pioneers who had fled Russian anti-Semitism in the early 1920s to build a Zionist nation. His mother, Genia Tversky, was a social force and political operator who became a member of the first Israeli Parliament, and the next four after that. She sacrificed her private life for public service and didn’t agonize greatly about the choice…

Amos was raised by his father, a veterinarian who hated religion and loved Russian literature, and who was amused by things people say:

…His father had turned away from an early career in medicine, Amos explained to friends, because “he thought animals had more real pain than people and complained a lot less.” Yosef Tversky was a serious man. At the same time, when he talked about his life and work, he brought his son to his knees with laughter about his experiences, and about the mysteries of existence.

Although Amos had a gift for math and science–he may have been more gifted than any other boy–he chose to study the humanities because he was fascinated by a teacher, Baruch Kurzweil. Amos loved Kurzweil’s classes in Hebrew literature and philosophy. Amos told others he was going to be a poet or literary critic.

Amos was small but athletic. During his final year in high school, he volunteered to become an elite soldier, a paratrooper. Amos made over fifty jumps. Soon he was made a platoon commander.

By late 1956, Amos was not merely a platoon commander but a recipient of one of the Israeli army’s highest awards for bravery. During a training exercise in front of the General Staff of the Israeli Defense Forces, one of his soldiers was assigned to clear a barbed wire fence with a bangalore torpedo. From the moment he pulled the string to activate the fuse, the soldier had twenty seconds to run for cover. The soldier pushed the torpedo under the fence, yanked the string, fainted, and collapsed on top of the explosive. Amos’s commanding officer shouted for everyone to stay put–to leave the unconscious soldier to die. Amos ignored him and sprinted from behind the wall that served as cover for his unit, grabbed the soldier, picked him up, hauled him ten yards, tossed him on the ground, and threw himself on top of him. The shrapnel from the explosion remained in Amos for the rest of his life. The Israeli army did not bestow honors for bravery lightly. As he handed Amos his award, Moshe Dayan, who had watched the entire episode, said, “You did a very stupid and brave thing and you won’t get away with it again.”

Amos was a great storyteller and also a true genius. Lewis writes about one time when Tel Aviv University threw a party for a physicist who had just won the Wolf Prize. Most of the leading physicists came to the party. But the prizewinner, by chance, ended up in a corner talking with Amos. (Amos had recently gotten interested in black holes.) The following day, the prizewinner called his hosts to find out the name of the “physicist” with whom he had been talking. They realized he had been talking with Amos, and told him that Amos was a psychologist rather than a physicist. The physicist replied:

“It’s not possible, he was the smartest of all the physicists.”

Most people who knew Amos thought that Amos was the smartest person they’d ever met. Moreover, he kept strange hours and had other unusual habits. When he wanted to go for a run, he’d just sprint out his front door and run until he could run no more. He didn’t pretend to be interested in whatever others expected him to be interested in. Rather, he excelled at doing exactly what he wanted to do and nothing else. He loved people, but didn’t like social norms and he would skip family vacation if he didn’t like the place. Most of his mail he left unopened.

People competed for Amos’s attention. As Lewis explains, many of Amos’s friends would ask themselves: “I know why I like him, but why does he like me?”

While at Hebrew University, Amos was studying both philosophy and psychology. But he decided a couple of years later that he would focus on psychology. He thought that philosophy had too many smart people studying too few problems, and some of the problems couldn’t be solved.

Many wondered how someone as bright, optimistic, logical, and clear-minded as Amos could end up in psychology. In an interview when he was in his mid-forties, Amos commented:

“It’s hard to know how people select a course in life. The big choices we make are practically random. The small choices probably tell us more about who we are. Which field we go into may depend upon which high school teacher we happen to meet. Who we marry may depend on who happens to be around at the right time of life. On the other hand, the small decisions are very systematic. That I became a psychologist is probably not very revealing. What kind of psychologist I am may depend upon deep traits.”

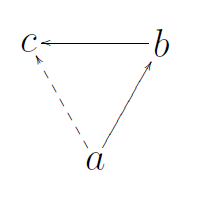

Amos became interested in decision making. While pursuing a PhD at the University of Michigan, Amos ran experiments on people making decisions involving small gambles. Economists had always assumed that people are rational. There were axioms of rationality that people were thought to follow, such as transitivity: if a person prefers A to B and B to C, then he must prefer A to C. However, Amos found that many people preferred A to B when considering A and B, B to C when considering B and C, and C to A when considering A and C. Many people violated transitivity. Amos didn’t generalize his findings at that point, however.

(Transitivity illustration by Thuluviel, Wikimedia Commons)

Next Amos studied how people compare things. He had read papers by the Berkeley psychologist Eleanor Rosch, who explored how people classified objects.

People said some strange things. For instance, they said that magenta was similar to red, but that red wasn’t similar to magenta. Amos spotted the contradiction and set out to generalize it. He asked people if they thought North Korea was like Red China. They said yes. He asked them if Red China was like North Korea–and they said no. People thought Tel Aviv was like New York but that New York was not like Tel Aviv. People thought that the number 103 was sort of like the number 100, but that 100 wasn’t like 103. People thought a toy train was a lot like a real train but that a real train was not like a toy train.

Amos came up with a theory, “features of similarity.” When people compare two things, they make a list of noticeable features. The more features two things have in common, the more similar they are. However, not all objects have the same number of noticeable features. New York has more than Tel Aviv.

This line of thinking led to some interesting insights:

When people picked coffee over tea, and tea over hot chocolate, and then turned around and picked hot chocolate over coffee–they weren’t comparing two drinks in some holistic manner. Hot drinks didn’t exist as points on some mental map at fixed distances from some ideal. They were collections of features. Those features might become more or less noticeable; their prominence in the mind depended on the context in which they were perceived. And the choice created its own context: Different features might assume greater prominence in the mind when the coffee was being compared to tea (caffeine) than when it was being compared to hot chocolate (sugar). And what was true of drinks might also be true of people, and ideas, and emotions.

ERRORS

Amos returned to Israel after marrying Barbara Gans, who was a fellow graduate student in psychology at the University of Michigan. Amos was now an assistant professor at Hebrew University.

Israel felt like a dangerous place because there was a sense that if the Arabs ever united instead of fighting each other, they could overrun Israel. Israel was unusual in how it treated its professors: as relevant. Amos gave talks about the latest theories in decision-making to Israeli generals.

Furthermore, everyone who was in Israel was in the army, including professors. On May 22, 1967, the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser announced that he was closing the Straits of Tiran to Israeli ships. Since most Israeli ships passed through the straits, Israel viewed the announcement as an act of war. Amos was given an infantry unit to command.

By June 7, Israel was in a war on three fronts against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. In the span of a week, Israel had won the war and the country was now twice as big. 679 had died. But because Israel was a small country, virtually everyone knew someone who had died.

Meanwhile, Danny was helping the Israeli Air Force to train fighter pilots. He noticed that the instructors viewed criticism as more useful than praise. After a good performance, the instructors would praise the pilot and then the pilot would usually perform worse on the next run. After a poor performance, the instructors would criticize the pilot and the pilot would usually perform better on the next run.

Danny explained that pilot performance regressed to the mean. An above average performance would usually be followed by worse performance–closer to the average. A below average performance would usually be followed by better performance–again closer to the average. Praise and criticism had little to do with it.

Danny was brilliant, though insecure and moody. He became interested in several different areas in psychology. Lewis adds:

That was another thing colleagues and students noticed about Danny: how quickly he moved on from his enthusiasms, how easily he accepted failure. It was as if he expected it. But he wasn’t afraid of it. He’d try anything. He thought of himself as someone who enjoyed, more than most, changing his mind.

Danny read about research by Eckhart Hess focused on measuring the dilation and contraction of the pupil in response to various stimuli. People’s pupils expanded when they saw pictures of good-looking people of the opposite sex. Their pupils contracted if shown a picture of a shark. If given a sweet drink, their pupils expanded. An unpleasant drink caused their pupils to contract. If you gave people five slightly differently flavored drinks, their pupils would faithfully record the relative degree of pleasure.

People reacted incredibly quickly, before they were entirely conscious of which one they liked best. “The essential sensitivity of the pupil response,” wrote Hess, “suggests that it can reveal preferences in some cases in which the actual taste differences are so slight that the subject cannot even articulate them.”

Danny tested how the pupil responded to a series of tasks requiring mental effort. Does intense mental activity hinder perception? Danny found that mental effort also caused the pupil to dilate.

THE COLLISION

Danny invited Amos to come to his seminar, Applications in Psychology, and talk about whatever he wanted.

Amos was now what people referred to, a bit confusingly, as a “mathematical psychologist.” Nonmathematical psychologists, like Danny, quietly viewed much of mathematical psychology as a series of pointless exercises conducted by people who were using their ability to do math as camouflage for how little of psychological interest they had to say. Mathematical psychologists, for their part, tended to view nonmathematical psychologists as simply too stupid to understand the importance of what they were saying. Amos was then at work with a team of mathematically gifted American academics on what would become a three-volume, molasses-dense, axiom-filled textbook calledFoundations of Measurement–more than a thousand pages of arguments and proofs of how to measure stuff.

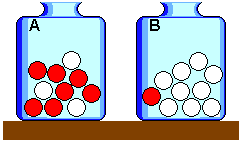

Instead of talking about his own research, Amos talked about a specific study of decision making and how people respond to new information. In the experiment, the psychologists presented people with two bags full of poker chips. Each bag contained both red poker chips and white poker chips. In one bag, 75 percent of the poker chips were white and 25 percent red. In the other bag, 75 percent red and 25 percent white. The subject would pick a bag randomly and, without looking in the bag, begin pulling poker chips out one at a time. After each draw, the subject had to give her best guess about whether the chosen bag contained mostly red or mostly white chips.

There was a correct answer to the question, and it was provided by Bayes’s theorem:

Bayes’s rule allowed you to calculate the true odds, after each new chip was pulled from it, that the book bag in question was the one with majority white, or majority red, chips. Before any chips had been withdrawn, those odds were 50:50–the bag in your hands was equally likely to be either majority red or majority white. But how did the odds shift after each new chip was revealed?

That depended, in a big way, on the so-called base rate: the percentage of red versus white chips in the bag… If you know that one bag contains 99 percent red chips and the other, 99 percent white chips, the color of the first chip drawn from the bag tells you a lot more than if you know that each bag contains only 51 percent red or white… In the case of the two bags known to be 75 percent-25 percent majority red or white, the odds that you are holding the bag containing mostly red chips rise by three times every time you draw a red chip, and are divided by three every time you draw a white chip. If the first chip you draw is red, there is a 3:1 (or 75 percent) chance that the bag you are holding is majority red. If the second chip you draw is also red, the odds rise to 9:1, or 90 percent. If the third chip you draw is white, they fall back to 3:1. And so on.

Were human beings good intuitive statisticians?

(Image by Honina, Wikimedia Commons)

Lewis notes that these experiments were radical and exciting at the time. Psychologists thought that they could gain insight into a number of real-world problems: investors reacting to an earnings report, political strategists responding to polls, doctors making a diagnosis, patients reacting to a diagnosis, coaches responding to a score, et cetera. A common example is when a woman is diagnosed with breast cancer from a single test. If the woman is in her twenties, it’s far more likely to be a misdiagnosis than if the woman is in her forties. That’s because the base rates are different: there’s a higher percentage of women in their forties than women in their twenties who have breast cancer.

Amos concluded that people do move in the right direction, however they usually don’t move nearly far enough. Danny didn’t think people were good intuitive statisticians at all. Although Danny was the best teacher of statistics at Hebrew University, he knew that he himself was not a good intuitive statistician because he frequently made simple mistakes like not accounting for the base rate.

Danny let Amos know that people are not good intuitive statisticians. Uncharacteristically, Amos didn’t argue much, except he wasn’t inclined to jettison the assumption of rationality:

Until you could replace a theory with a better theory–a theory that better predicted what actually happened–you didn’t chuck a theory out. Theories ordered knowledge, and allowed for better prediction. The best working theory in social science just then was that people were rational–or, at the very least, decent intuitive statisticians. They were good at interpreting new information, and at judging probabilities. They of course made mistakes, but their mistakes were a product of emotions, and the emotions were random, and so could be safely ignored.

Note: To say that the mistakes are random means that mistakes in one direction will be cancelled out by mistakes in the other direction. This implies that the aggregate market can still be rational and efficient.

Amos left Danny’s class feeling doubtful about the assumption of rationality. By the fall of 1969, Amos and Danny were together nearly all the time. Many others wondered at how two extremely different personalities could wind up so close. Lewis:

Danny was a Holocaust kid; Amos was a swaggering Sabra–the slang term for a native Israeli. Danny was always sure he was wrong. Amos was always sure he was right. Amos was the life of every party; Danny didn’t go to parties. Amos was loose and informal; even when he made a stab at informality, Danny felt as if he had descended from some formal place. With Amos you always just picked up where you left off, no matter how long it had been since you last saw him. With Danny there was always a sense you were starting over, even if you had been with him just yesterday. Amos was tone-deaf but would nevertheless sing Hebrew folk songs with great gusto. Danny was the sort of person who might be in possession of a lovely singing voice that he would never discover. Amos was a one-man wrecking ball for illogical arguments; when Danny heard an illogical argument, he asked,What might that be true of? Danny was a pessimist. Amos was not merely an optimist; Amoswilled himself to be optimistic, because he had decided pessimism was stupid.

Lewis later writes:

But there was another story to be told, about how much Danny and Amos had in common. Both were grandsons of Eastern European rabbis, for a start. Both were explicitly interested in how people functioned when there were in a normal “unemotional” state. Both wanted to do science. Both wanted to search for simple, powerful truths. As complicated as Danny might have been, he still longed to do “the psychology of single questions,” and as complicated as Amos’s work might have seemed, his instinct was to cut through endless bullshit to the simple nub of any matter. Both men were blessed with shockingly fertile minds.

After testing scientists with statistical questions, Amos and Danny found that even most scientists are not good intuitive statisticians. Amos and Danny wrote a paper about their findings, “A Belief in the Law of Small Numbers.” Essentially, scientists–including statisticians–tended to assume that any given sample of a large population was more representative of that population than it actually was.

Amos and Danny had suspected that many scientists would make the mistake of relying too much on a small sample. Why did they suspect this? Because Danny himself had made the mistake many times. Soon Amos and Danny realized that everyone was prone to the same mistakes that Danny would make. In this way, Amos and Danny developed a series of hypotheses to test.

THE MIND’S RULES

The Oregon Research Institute is dedicated to studying human behavior. It was started in 1960 by psychologist Paul Hoffman. Lewis observes that many of the psychologists who joined the institute shared an interest in Paul Meehl’s book,Clinical vs. Statistical Prediction. The book showed how algorithms usually perform better than psychologists when trying to diagnose patients or predict their behavior.

In 1986, thirty two years after publishing his book, Meehl argued that algorithms outperform human experts in a wide variety of areas. That’s what the vast majority of studies had demonstrated by then. Here’s a more recent meta-analysis:https://boolefund.com/simple-quant-models-beat-experts-in-a-wide-variety-of-areas/

In the 1960s, researchers at the institute wanted to build a model of how experts make decisions. One study they did was to ask radiologists how they determined if a stomach ulcer was benign or malignant. Lewis explains:

The Oregon researchers began by creating, as a starting point, a very simple algorithm, in which the likelihood that an ulcer was malignant depended on the seven factors the doctors had mentioned, equally weighted. The researchers then asked the doctors to judge the probability of cancer in ninety-six different individual stomach ulcers, on a seven-point scale from “definitely malignant” to “definitely benign.” Without telling the doctors what they were up to, they showed them each ulcer twice, mixing up the duplicates randomly in the pile so the doctors wouldn’t notice they were being asked to diagnose the exact same ulcer they had already diagnosed.

Initially the researchers planned to start with a simple model and then gradually build a more complex model. But then they got the results of the first round of questions. It turned out that the simple statistical model often seemed as good or better than experts at diagnosing cancer. Moreover, the experts didn’t agree with each other and frequently even contradicted themselves when viewing the same image a second time.

Next, the Oregon experimenters explicitly tested a simple algorithm against human experts: Was a simple algorithm better than human experts? Yes.

If you wanted to know whether you had cancer or not, you were better off using the algorithm that the researchers had created than you were asking the radiologist to study the X-ray. The simple algorithm had outperformed not merely the group of doctors; it had outperformed even the single best doctor.

(Algorithm illustration by Blankstock)

The strange thing was that the simple model was built on the factors that the doctors themselves had suggested as important. While the algorithm was absolutely consistent, it appeared that human experts were rather inconsistent, most likely due to things like boredom, fatigue, illness, or other distractions.

Amos and Danny continued asking people questions where the odds were hard or impossible to know. Lewis:

…Danny made the mistakes, noticed that he had made the mistakes, and theorized about why he had made the mistakes, and Amos became so engrossed by both Danny’s mistakes and his perceptions of those mistakes that he at least pretended to have been tempted to make the same ones.

Once again, Amos and Danny spent hour after hour after hour together talking, laughing, and developing hypotheses to test. Occasionally Danny would say that he was out of ideas. Amos would always laugh at this–he remarked later, “Danny has more ideas in one minute than a hundred people have in a hundred years.” When they wrote, Amos and Danny would sit right next to each other at the typewriter. Danny explained:

“We were sharing a mind.”

The second paper Amos and Danny did–as a follow-up on their first paper, “Belief in the Law of Small Numbers”–focused on how people actually make decisions. The mind typically doesn’t calculate probabilities. What does it do? It uses rules of thumb, or heuristics, said Amos and Danny. In other words, people develop mental models, and then compare whatever they are judging to their mental models. Amos and Danny wrote:

“Our thesis is that, in many situations, an event A is judged to be more probable than an event B whenever A appears more representative than B.”

What’s a bit tricky is that often the mind’s rules of thumb lead to correct decisions and judgments. If that weren’t the case, the mind would not have evolved this ability. For the same reason, however, when the mind makes mistakes because it relies on rules of thumb, those mistakes are not random, but systematic.

When does the mind’s heuristics lead to serious mistakes? When the mind is trying to judge something that has a random component. That was one answer. What’s interesting is that the mind can be taught the correct rule about how sample size impacts sampling variance; however, the mind rarely follows the correct statistical rule, even when it knows it.

For their third paper, Amos and Danny focused on theavailability heuristic. (The second paper had been about therepresentativeness heuristic.) In one question, Amos and Danny asked their subjects to judge whether the letter “k” is more frequently the first letter of a word or the third letter of a word. Most people thought “k” was more frequently the first letter because they could more easily recall examples where “k” was the first letter.

The more easily people can call some scenario to mind–the more available it is to them–the more probable they find it to be. An fact or incident that was especially vivid, or recent, or common–or anything that happened to preoccupy a person–was likely to be recalled with special ease and so be disproportionately weighted in any judgment. Danny and Amos had noticed how oddly, and often unreliably, their own minds recalculated the odds, in light of some recent or memorable experience. For instance, after they drove past a gruesome car crash on the highway, they slowed down: Their sense of the odds of being in a crash had changed. After seeing a movie that dramatizes nuclear war, they worried more about nuclear war; indeed, they felt that it was more likely to happen.

Amos and Danny ran similar experiments and found similar results. The mind’s rules of thumb, although often useful, consistently made the same mistakes in certain situations. It was similar to how the eye consistently falls for certain optical illusions.

Another rule of thumb Amos and Danny identified was theanchoring and adjustment heuristic. One famous experiment they did was to ask people to spin a wheel of fortune, which would stop on a number between 0 and 100, and then guess the percentage of African nations in the United Nations. The people who spun higher numbers tended to guess a higher percentage than those who spun lower numbers, even though the number spun was purely random and was irrelevant to the question.

THE RULES OF PREDICTION

For Amos and Danny, a prediction is a judgment under uncertainty. They observed:

“In making predictions and judgments under uncertainty, people do not appear to follow the calculus of chance or the statistical theory of prediction. Instead, they rely on a limited number of heuristics which sometimes yield reasonable judgments and sometimes lead to severe and systematic error.”

In 1972, Amos gave talks on the heuristics he and Danny had uncovered. In the fifth and final talk, Amos spoke about historical judgment, saying:

“In the course of our personal and professional lives, we often run into situations that appear puzzling at first blush. We cannot see for the life of us why Mr. X acted in a particular way, we cannot understand how the experimental results came out the way they did, etc. Typically, however, within a very short time we come up with an explanation, a hypothesis, or an interpretation of the facts that renders them understandable, coherent, or natural. The same phenomenon is observed in perception. People are very good at detecting patterns and trends even in random data. In contrast to our skill in inventing scenarios, explanations, and interpretations, our ability to assess their likelihood, or to evaluate them critically, is grossly inadequate. Once we have adopted a particular hypothesis or interpretation, we grossly exaggerate the likelihood of that hypothesis, and find it very difficult to see things in any other way.”

In one experiment, Amos and Danny asked students to predict various future events that would result from Nixon’s upcoming visit to China and Russia. What was intriguing was what happened later: If a predicted event had occurred, people overestimated the likelihood they had previously assigned to that event. Similarly, if a predicted event had not occurred, people tended to claim that they always thought it was unlikely. This came to be calledhindsight bias.

- A possible event that had occurred was seen in hindsight to be more predictable than it actually was.

- A possible event that had not occurred was seen in hindsight to be less likely that it actually was.

As Amos said:

All too often, we find ourselves unable to predict what will happen; yet after the fact we explain what did happen with a great deal of confidence. This “ability” to explain that which we cannot predict, even in the absence of any additional information, represents an important, though subtle, flaw in our reasoning. It leads us to believe that there is a less uncertain world than there actually is…

Experts from many walks of life–from political pundits to historians–tend to impose an imagined order on random events from the past. They change their stories to “explain”–and by implication, “predict” (in hindsight)–whatever random set of events occurred. This ishindsight bias, or “creeping determinism.”

Hindsight bias can create serious problems: If you believe that random events in the past are more predictable than they actually were, you will tend to see the future as more predictable than it actually is. You will be surprised much more often than you should be.

GOING VIRAL

Part of Don Redelmeier’s job at Sunnybrook Hospital (located in a Toronto suburb) was to check the thinking of specialists for mental mistakes. In North America, more people died every year as a result of preventable accidents in hospitals than died in car accidents. Redelmeier focused especially on clinical misjudgment. Lewis:

Doctors tended to pay attention mainly to what they were asked to pay attention to, and to miss some bigger picture. They sometimes failed to notice what they were not directly assigned to notice.

[…]

Doctors tended to see only what they were trained to see… A patient received treatment for something that was obviously wrong with him, from a specialist oblivious to the possibility that some less obvious thing might also be wrong with him. The less obvious thing, on occasion, could kill a person.

When he was only seventeen years old, Redelmeier had read an article by Kahneman and Tversky, “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Lewis writes:

What struck Redelmeier wasn’t the idea that people make mistakes. Of course people made mistakes! What was so compelling is that the mistakes were predictable and systematic. They seemed ingrained in human nature.

One major problem in medicine is that the culture does not like uncertainty.

To acknowledge uncertainty was to admit the possibility of error. The entire profession had arranged itself as if to confirm the wisdom of its decisions. Whenever a patient recovered, for instance, the doctor typically attributed the recovery to the treatment he had prescribed, without any solid evidence the treatment was responsible… [As Redelmeier said:] “So many diseases are self-limiting. They will cure themselves. People who are in distress seek care. When they seek care, physicians feel the need to do something. You put leeches on; the condition improves. And that can propel a lifetime of leeches. A lifetime of overprescribing antibiotics. A lifetime of giving tonsillectomies to people with ear infections. You try it and they get better the next day and it is so compelling…”

One day, Redelmeier was going to have lunch with Amos Tversky. Hal Sox, Redelmeier’s superior, told him just to sit quietly and listen, because Tversky was like Einstein, “one for the ages.” Sox had coauthored a paper Amos had done about medicine. They explored how doctors and patients thought about gains and losses based upon how the choices were framed.

An example was lung cancer. You could treat it with surgery or radiation. Surgery was more likely to extend your life, but there was a 10 percent chance of dying. If you told people that surgery had a 90 percent chance of success, 82 percent of patients elected to have surgery. But if you told people that surgery had a 10 percent chance of killing them, only 54 percent chose surgery. In a life-and-death decision, people made different choices based not on the odds, but on how the odds were framed.

Amos and Redelmeier ended up doing a paper:

[Their paper] showed that, in treating individual patients, the doctors behaved differently than they did when they designed ideal treatments for groups of patients with the same symptoms. They were likely to order additional tests to avoid raising troubling issues, and less likely to ask if patients wished to donate their organs if they died. In treating individual patients, doctors often did things they would disapprove of if they were creating a public policy to treat groups of patients with the exact same illness…

The point was not that the doctor was incorrectly or inadequately treating individual patients. The point was that he could not treat his patient one way, and groups of patients suffering from precisely the same problem in another way, and be doing his best in both cases. Both could not be right.

Redelmeier pointed out that the facade of rationality and science and logic is “a partial lie.”

In late 1988 or early 1989, Amos introduced Redelmeier to Danny. One of the recent things Danny had been studying was people’s experience of happiness versus their memories of happiness. Danny also looked at how people experienced pain versus how they remembered it.

One experiment involved sticking the subject’s arms into a bucket of ice water.

[People’s] memory of pain was different from their experience of it. They remembered moments of maximum pain, and they remembered, especially, how they felt the moment the pain ended. But they didn’t particularly remember the length of the painful experience. If you stuck people’s arms in ice buckets for three minutes but warmed the water just a bit for another minute or so before allowing them to flee the lab, they remembered the experience more fondly than if you stuck their arms in the bucket for three minutes and removed them at a moment of maximum misery. If you asked them to choose one experience to repeat, they’d take the first session. That is, people preferred to endure more total pain so long as the experience ended on a more pleasant note.

Redelmeier tested this hypothesis on seven hundred people who underwent a colonoscopy. The results supported Danny’s finding.

BIRTH OF THE WARRIOR PSYCHOLOGIST

In 1973, the armies of Egypt and Syria surprised Israel on Yom Kippur. Amos and Danny left California for Israeli. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had promised to shoot down any commercial airliners entering Israel. That was because, as usual, Israelis in other parts of the world would return to Israel during a war. Amos and Danny managed to land in Tel Aviv on an El Al flight. The plane had descended in total darkness. Amos and Danny were to join the psychology field unit.

Amos and Danny set out in a jeep and went to the battlefield in order to study how to improve the morale of the troops. Their fellow psychologists thought they were crazy. It wasn’t just enemy tanks and planes. Land mines were everywhere. And it was easy to get lost. People were more concerned about Danny than Amos because Amos was more of a fighter. But Danny proved to be more useful because he had a gift for finding solutions to problems where others hadn’t even noticed the problem.

Soon after the war, Amos and Danny studied public decision making.

Both Amos and Danny thought that voters and shareholders and all the other people who lived with the consequences of high-level decisions might come to develop a better understanding of the nature of decision making. They would learn to evaluate a decision not by its outcomes–whether it turned out to be right or wrong–but by the process that led to it. The job of the decision maker wasn’t to be right but to figure out the odds in any decision and play them well.

It turned out that Israeli leaders often agreed about probabilities, but didn’t pay much attention to them when making decisions on whether to negotiate for peace or fight instead. The director-general of the Israeli Foreign Ministry wasn’t even interested in the best estimates of probabilities. Instead, he made it clear that he preferred to trust his gut. Lewis quotes Danny:

“That was the moment I gave up on decision analysis. No one ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story.”

Some time later, Amos introduced Danny to the field of decision making under uncertainty. Many students of the field studied subjects in labs making hypothetical gambles.

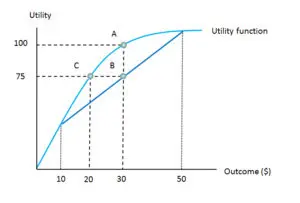

The central theory in decision making under uncertainty had been published in the 1730s by the Swiss mathematician Daniel Bernoulli. Bernoulli argued that people make probabilistic decisions so as to maximize their expected utility. Bernoulli also argued that people are “risk averse”: each new dollar has less utility than the one before. This theory seemed to describe some human behavior.

(Utility as a function of outcomes, Global Water Forum, Wikimedia Commons)

The utility function above illustratesrisk aversion: Each additional dollar–between $10 and $50–has less utility than the one before.

In 1944, John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern published the axioms of rational decision making. One axiom was “transitivity”: if you preferred A to B, and B to C, then you preferred A to C. Another axiom was “independence”: if you preferred A to B, your preference between A and B wouldn’t change if some other alternative (say D) was introduced.

Many people, including nearly all economists, accepted von Neumann and Morgenstern’s axioms of rationality as a fair description for how people actually made choices. Danny recalls that Amos regarded the axioms as a “sacred thing.”

By the summer of 1973, Amos was searching for ways to undo the reigning theory of decision making, just as he and Danny had undone the idea that human judgment followed the precepts of statistical theory.

Lewis records that by the end of 1973, Amos and Danny were spending six hours a day together. One insight Danny had about utility was that it wasn’t levels of wealth that represented utility (or happiness); it was changes in wealth–gains and losses–that mattered.

THE ISOLATION EFFECT

Many of the ideas Amos and Danny had could not be attributed to either one of them individually, but seemed to come from their interaction. That’s why they always shared credit equally–they switched the order of their names for each new paper, and the order for their very first paper had been determined by a coin toss.

In this case, though, it was clear that Danny had the insight that gains and losses are more important than levels of utility. However, Amos then asked a question with profound implications: “What if we flipped the signs?” Instead of asking whether someone preferred a 50-50 gamble for $1,000 or $500 for sure, they asked this instead:

Which of the following do you prefer?

- Gift A: A lottery ticket that offers a 50 percent chance of losing $1,000

- Gift B: A certain loss of $500

When the question was put in terms of possible gains, people preferred the sure thing. But when the question was put in terms of possible losses, people preferred to gamble. Lewis elaborates:

The desire to avoid loss ran deep, and expressed itself most clearly when the gamble came with the possibility of both loss and gain. That is, when it was like most gambles in life. To get most people to flip a coin for a hundred bucks, you had to offer them far better than even odds. If they were going to loss $100 if the coin landed on heads, they would need to win $200 if it landed on tails. To get them to flip a coin for ten thousand bucks, you had to offer them even better odds than you offered them for flipping it for a hundred.

It was easy to see thatloss aversion had evolutionary advantages. People who weren’t sensitive to pain or loss probably wouldn’t survive very long.

A loss is when you end up worse than your status quo. Yet determining the status quo can be tricky because often it’s a state of mind. Amos and Danny gave this example:

Problem A. In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $1,000. You are now required to choose between the following options:

- Option 1. A 50 percent chance to win $1,000

- Option 2. A gift of $500

Problem B. In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $2,000. You are now required to choose between the following options:

- Option 3. A 50 percent chance to lose $1,000

- Option 4. A sure loss of $500

In Problem A, most people picked Option 2, the sure thing. In Problem B, most people chose Option 3, the gamble. However, the two problems are logically identical: Overall, you’re choosing between $1,500 for sure versus a 50-50 chance of either $2,000 or $1,000.

What Amos and Danny had discovered wasframing. The way a choice is framed can impact the way people choose, even if two different frames both refer to exactly the same choice, logically speaking. Consider the Asian Disease Problem, invented by Amos and Danny. People were randomly divided into two groups. The first group was given this question:

Problem 1. Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative problems to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimate of the consequence of the programs is as follows:

- If Program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

- If Program B is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that 600 people will be saved, and a 2/3 probability that no one will be saved.

Which of the two programs would you favor?

People overwhelming chose Program A, saving 200 people for sure.

The second group was given the same problem, but was offered these two choices:

- If Program C is adopted, 400 people will die.

- If Program D is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that nobody will die and a 2/3 probability that 600 people will die.

People overwhelmingly chose Program D. Once again, the underlying choice in each problem is logically identical. If you save 200 for sure, then 400 will die for sure. Because of framing, however, people make inconsistent choices.

THIS CLOUD OF POSSIBILITY

In 1984, Amos learned he had been given a MacArthur “genius” grant. He was upset, as Lewis explains:

Amos disliked prizes. He thought that they exaggerated the differences between people, did more harm than good, and created more misery than joy, as for every winner there were many others who deserved to win, or felt they did.

Amos was angry because he thought that being given the award, and Danny not being given the award, was “a death blow” for the collaboration between him and Danny. Nonetheless, Amos kept on receiving prizes and honors, and Danny kept on not receiving them. Furthermore, ever more books and articles came forth praising Amos for the work he had done with Danny, as if he had done it alone.

Amos continued to be invited to lectures, seminars, and conferences. Also, many groups asked him for his advice:

United States congressmen called him for advice on bills their were drafting. The National Basketball Association called to hear his argument about statistical fallacies in basketball. The United States Secret Service flew him to Washington so that he could advise them on how to predict and deter threats to the political leaders under their protection. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization flew him to the French Alps to teach them about how people made decisions in conditions of uncertainty. Amos seemed able to walk into any problem, and make the people dealing with it feel as if he grasped its essence better than they did.

Despite the work of Amos and Danny, many economists and decision theorists continued to believe in rationality. These scientists argued that Amos and Danny had overstated human fallibility. So Amos looked for new ways to convince others. For instance, Amos asked people: Which is more likely to happen in the next year, that a thousand Americans will die in a flood, or that an earthquake in California will trigger a massive flood that will drown a thousand Americans? Most people thought the second scenario was more likely; however, the second scenario is a special case of the first scenario, and therefore the first scenario is automatically more likely.

Amos and Danny came up with an even more stark example. They presented people with the following:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which of the two alternatives is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Eighty-five percent of the subjects thought that the second scenario is more likely than the first scenario. However, just like the previous problem, the second scenario is a special case of the first scenario, and so the first scenario is automatically more likely than the second scenario.

Say there are 50 people who fit the description, are named Linda, and are bank tellers. Of those 50, how many are also active in the feminist movement? Perhaps quite a few, but certainly not all 50.

Amos and Danny constructed a similar problem for doctors. But the majority of doctors made the same error.

Lewis:

The paper Amos and Danny set out to write about what they were now calling “the conjunction fallacy” must have felt to Amos like an argument ender–that is, if the argument was about whether the human mind reasoned probabilistically, instead of the ways Danny and Amos had suggested. They walked the reader through how and why people violated “perhaps the simplest and the most basic qualitative law of probability.” They explained that people chose the more detailed description, even though it was less probable, because it was more “representative.” They pointed out some places in the real world where this kink in the mind might have serious consequences. Any prediction, for instance, could be made to seem more believable, even as it became less likely, if it was filled with internally consistent details. And any lawyer could at once make a case seem more persuasive, even as he made the truth of it less likely, by adding “representative” details to his description of people and events.

Around the time Amos and Danny published work with these examples, their collaboration had come to be nothing like it was before. Lewis writes:

It had taken Danny the longest time to understand his own value. Now he could see that the work Amos had done alone was not as good as the work they had done together. The joint work always attracted more interest and higher praise than anything Amos had done alone.

Danny pointed out to Amos that Amos that been a member of the National Academy of Sciences for a decade, but Danny still wasn’t a member. Danny asked Amos why he hadn’t put Danny’s name forward.

A bit later, Danny told Amos they were no longer friends. Three days after that, Amos called Danny. Amos learned that his body was riddled with cancer and that he had at most six months to live.

BOOLE MICROCAP FUND

An equal weighted group of micro caps generally far outperforms an equal weighted (or cap-weighted) group of larger stocks over time. See the historical chart here: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

This outperformance increases significantly by focusing on cheap micro caps. Performance can be further boosted by isolating cheap microcap companies that show improving fundamentals. We rank microcap stocks based on these and similar criteria.

There are roughly 10-20 positions in the portfolio. The size of each position is determined by its rank. Typically the largest position is 15-20% (at cost), while the average position is 8-10% (at cost). Positions are held for 3 to 5 years unless a stock approachesintrinsic value sooner or an error has been discovered.

The mission of the Boole Fund is to outperform the S&P 500 Index by at least 5% per year (net of fees) over 5-year periods. We also aim to outpace the Russell Microcap Index by at least 2% per year (net). The Boole Fund has low fees.

If you are interested in finding out more, please e-mail me or leave a comment.

My e-mail: jb@boolefund.com

Disclosures: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed.No part of this article may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of Boole Capital, LLC.

Best view in the town !