Shoe Dog is the autobiography of Phil Knight, the creator of Nike. Bill Gates mentioned this book as one of his favorites in 2016, saying it was “a refreshingly honest reminder of what the path to business success really looks like: messy, precarious, and riddled with mistakes.”

After the introduction, Knight has a chapter for each year, starting in 1962 and going through 1980.

DAWN

Knight introduces his story:

On paper, I thought, I’m an adult. Graduated from a good college – University of Oregon. Earned a master’s from a top business school – Stanford. Survived a yearlong hitch in the U.S. Army – Fort Lewis and Fort Eustis. My resume said I was a learned, accomplished soldier, a twenty-four-year-old man in full… So why, I wondered, why do I still feel like a kid?

Worse, like the same shy, pale, rail-thin kid I’d always been.

Maybe because I still hadn’t experienced anything of life. Least of all its many temptations and excitements. I hadn’t smoked a cigarette, hadn’t tried a drug. I hadn’t broken a rule, let alone a law. The 1960s were just underway, the age of rebellion, and I was the only person in America who hadn’t yet rebelled. I couldn’t think of one time I’d cut loose, done the unexpected.

I’d never even been with a girl.

If I tended to dwell on all the things I wasn’t, the reason was simple. Those were the things I knew best. I’d have found it difficult to see who or what exactly I was, or might become. Like all my friends I wanted to be successful. Unlike my friends I didn’t know what that meant. Money? Maybe. Wife? Kids? House? Sure, if I was lucky. These were the goals I was taught to aspire to, and part of me did aspire to them, instinctively. But deep down I was searching for something else, something more. I had an aching sense that our time is short, shorter than we ever know, short as a morning run, and I wanted mine to be meaningful. And purposeful. And creative. And important. Above all… different.

I wanted to leave a mark on the world…

And then it happened. As my young heart began to thump, as my pink lungs expanded like the wings of a bird, as the trees turned to greenish blurs, I saw it all before me, exactly what I wanted my life to be. Play.

Yes, I thought. That’s it. That’s the word. The secret of happiness, I’d always suspected, the essence of beauty or truth, or all we ever need to know of either, lay somewhere in that moment when the ball is in midair, when both boxers sense that approach of the bell, when the runners near the finish line and the crowd rises as one. There’s a kind of exuberant clarity in that pulsing half second before winning and losing are decided. I wanted that, whatever that was, to be my life, my daily life.

(Sweet Sixteen Syracuse vs. Gonzaga, March 25, 2016, Photo by Ryan Dickey, Wikimedia Commons)

Knight continues:

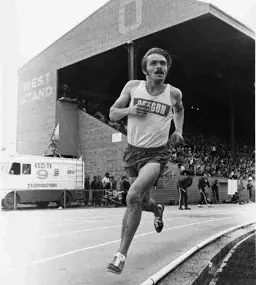

At different times, I’d fantasized about becoming a great novelist, a great journalist, a great statesman. But the ultimate dream was always to be a great athlete. Sadly, fate had made me good, not great. At twenty-four, I was finally resigned to that fact. I’d run track at Oregon, and I’d distinguished myself, lettering three of four years. But that was that, the end. Now, as I began to clip off one brisk six-minute mile after another, as the rising sun set fire to the lowest needles of the pines, I asked myself: What if there were a way, without being an athlete, to feel what athletes feel? To play all the time, instead of working? Or else to enjoy work so much that it becomes essentially the same thing.

I was suddenly smiling. Almost laughing. Drenched in sweat, moving as gracefully and effortlessly as I ever did, I saw my Crazy Idea shining up ahead, and it didn’t look all that crazy. It didn’t even look like an idea. It looked like a place. It looked like a person, or some life force that existed long before I did, separate from me, but also part of me. Waiting for me, but also hiding from me. That might sound a little high-flown, a little crazy. But that’s how I felt back then.

…At twenty-four, I did have a crazy idea, and somehow, despite being dizzy with existential angst, and fears about the future, and doubts about myself, as all young men and women in their midtwenties are, I did decide that the world is made up of crazy ideas. History is one long processional of crazy ideas. The things I loved most – books, sports, democracy, free enterprise – started as crazy ideas.

For that matter, few ideas are as crazy as my favorite thing, running. It’s hard. It’s painful. It’s risky. The rewards are few and far from guaranteed… Whatever pleasures or gains you drive from the act of running, you must find them within. It’s all in how you frame it, how you sell it to yourself.

(Runner silhouette, Illustration by Msanca)

Knight:

So that morning in 1962 I told myself: Let everyone else call your idea crazy… just keep going. Don’t stop. Don’t even think about stopping until you get there, and don’t give much thought to where ‘there’ is. Whatever comes, just don’t stop.

That’s the precocious, prescient, urgent advice I managed to give myself, out of the blue, and somehow managed to take. Half a century later, I believe it’s the best advice – maybe the only advice – any of us should ever give.

1962

Knight explains that his crazy idea started as a research paper for a seminar on entrepreneurship at Stanford. He became obsessed with the project. As a runner, he knew about shoes. He also knew that some Japanese products, such as cameras, had recently gained much market share. Perhaps Japanese running shoes might do the same thing.

When Knight presented his idea to his classmates, everyone was bored. No one asked any questions. But Knight held on to his idea. He imagined pitching it to a Japanese shoe company. Knight also conceived of the idea of seeing the world on his way to Japan. He wanted to see “the world’s most beautiful and wondrous places.”

And its most sacred. Of course I wanted to taste other foods, hear other languages, dive into other cultures, but what I really craved was connection with a capital C. I wanted to experience what the Chinese call Tao, the Greeks call Logos, the Hindus call Jnana, the Buddhists call Dharma. What the Christians call Spirit. Before setting out on my own personal life voyage, I thought, let me first understand the greater voyage of humankind. Let me explore the grandest temples and churches and shrines, the holiest rivers and mountaintops. Let me feel the presence of… God?

Yes, I told myself, yes. For lack of a better word, God.

But Knight needed his father’s blessing and cash in order to make the trip around the world.

At the time, most people had never been on an airplane. Also, Knight’s father’s father had died in an air crash. As for the shoe company idea, Knight was keenly aware that twenty-six out of twenty-seven new companies failed. Knight then notes that his father, besides being a conventional Episcopalian, also liked respectability. Traveling around the world just wasn’t done except by beatniks and hipsters.

Knight then adds:

Possibly, the main reason for my father’s respectability fixation was a fear of his inner chaos. I felt this, viscerally, because every now and then that chaos would burst forth.

Knight tells about having to pick his father up from his club. On these evenings, Knight’s father had had too much to drink. But father and son would pretend nothing was wrong. They would talk sports.

Knight’s mom’s mom, “Mom Hatfield” – from Roseburg, Oregon – warned “Buck” (Knight’s nickname) that the Japanese would take him prisoner and gouge out his eyeballs. Knight’s sisters, four years younger (twins), Jeanne and Joanne, had no reaction. His mom didn’t say anything, as usual, but seemed proud of his decision.

Knight asked a Stanford classmate, Carter, a college hoops star, to come with him. Carter loved to read good books. And he liked Buck’s idea.

The first stop was Honolulu. After seeing Hawaiian girls, then diving into the warm ocean, Buck told Carter they should stay. What about the plan? Plans change. Carter liked the new idea and grinned.

They got jobs selling Encyclopedias door-to-door. But their main mission was learning how to surf. “Life was heaven.” Except that Buck couldn’t sell encyclopedias. He thought he was getting shier as he got older.

So he tried a job selling securities. Specifically, Dreyfus funds for Investors Overseas Services, Bernard Cornfeld’s firm. Knight had better luck with this.

Eventually, the time came for Buck and Carter to continue on their trip around the world. However, Carter wasn’t sure.

He’d met a girl. A beautiful Hawaiian teenager with long brown legs and jet-black eyes, the kind of girl who’d greeted our airplane, the kind I dreamed of having and never would. He wanted to stick around, and how could I argue?

Buck hesitated, not sure he wanted to continue on alone. But he decided not to stop his journey. He bought a plane ticket that was good for one year on any airline going anywhere.

When Knight got to Tokyo, much of the city was black because it still hadn’t been rebuilt after the bombing.

American B-29s. Superfortresses. Over a span of several nights in the summer of 1944, waves of them dropped 750,000 pounds of bombs, most filled with gasoline and flammable jelly. One of the world’s oldest cities, Tokyo was made largely of wood, so the bombs set off a hurricane of fire. Some three hundred thousand people were burned alive, instantly, four times the number who died in Hiroshima. More than a million were gruesomely injured. And nearly 80 percent of the buildings were vaporized. For long, solemn stretches the cab driver and I said nothing. There was nothing to say.

Fortunately, Buck’s father knew some people in Tokyo at United Press International. They advised Buck to talk to two ex-GI’s who ran a monthly magazine, theImporter.

First, Knight spent long periods of time in walled gardens reading about Buddhism and Shinto. He liked the concept of kensho, or sartori – a flash of enlightenment.

But according to Zen, reality is nonlinear. No past, no present. All is now. That required Knight to change his thinking. There is no self. Even in competition, all is one.

Knight decided to mix it up and visited the Tokyo Stock Exchange – Tosho. All was madness and yelling. Is this what it’s all about?

Knight sought peace and enlightenment again. He visited the garden of the nineteenth century emperor Meiji and his empress. This particular place was thought to possess great spiritual power. Buck sat beneath the ginkgo trees, beside the gorgeous torii gate, which was thought of as a portal to the sacred.

Next it was Tsukiji, the world’s largest fish market. Tosho all over again.

Then to the lakes region in the Northern Hakone mountains. An area that inspired many of the great Zen poets.

Knight went to see the two ex-GI’s. They told him how they’d fallen in love with Japan during the Occupation. So they stayed. They had managed to keep the import magazine going for seventeen years thus far.

Knight told them he liked the Tiger shoes produced by Onitsuka Co. in Kobe, Japan. The ex-GI’s gave him tips on negotiating with the Japanese:

‘No one ever turns you down, flat. No one ever says, straight out, no. But they don’t say yes, either. They speak in circles, sentences with no clear subject or object. Don’t be discouraged, but don’t be cocky. You might leave a man’s office thinking you’ve blown it, when in fact he’s ready to do a deal. You might leave thinking you’ve closed a deal, when in fact you’ve just been rejected. You never know.’

Knight decided to visit Onitsuka right away, with the advice fresh in his mind. He managed to get an appointment, but got lost and arrived late.

When he did arrive, several executives met him. Ken Miyazaki showed him the factory. Then they went to a conference room.

Knight had rehearsed this scene his head, just like he used to visualize his races. But one thing he hadn’t prepared for was the recent history of World War II hanging over everything. The Japanese had heroically rebuilt, putting the war behind them. And these Japanese executives were young. Still, Knight thought, their fathers and uncles had tried to kill his. In brief, Knight hesitated and coughed, then finally said, “Gentlemen.”

Mr. Miyazaki interrupted, “Mr. Knight. What company are you with?”

Knight replied, “Ah, yes. Good question.” Knight experienced fight or flight for a moment. A random jumble of thoughts flickered in his mind until he visualized his wall of blue ribbons from track. “Blue Ribbon… Gentleman, I represent Blue Ribbon Sports of Portland, Oregon.”

Knight presented his basic argument, which was that the American shoe market was huge and largely untapped. If Onitsuka could produce good shoes and price them below Adidas, it could be highly profitable. Knight had spent so much time on his research paper at Stanford that he could simply quote it and come across as eloquent.

The Japanese executives started talking excitedly together, then suddenly stood up and left the room. Knight didn’t know if he had been rejected. Perhaps he should leave. He waited.

Then they came back into the room with sketches of different Tiger shoes. They told him they had been thinking about the American market for some time. They asked Knight how big he thought the market could be. Knight tossed out, “$1 billion.” He doesn’t know where the number came from.

They asked him if Blue Ribbon would be interested in selling Tigers in the United States. Yes, please send samples to this address, Knight said, and I’ll send a money order for fifty dollars.

Knight considered returning home to get a jump on the new business. But then he decided to finish his trek around the world.

Hong Kong, then the Phillipines.

I was fascinated by all the great generals, from Alexander the Great to George Patton. I hated war, but I loved the warrior spirit. I hated the sword, but loved the samurai. And of all the great fighting men in history I found MacArthur the most compelling. Those Ray-Bans, that corncob pipe – the man didn’t lack for confidence. Brilliant tactician, master motivator, he also went on to head the U.S. Olympic Committee. How could I not love him?

Of course, he was deeply flawed. But he knew that…

Bangkok. He made his way to Wat Phra Kaew, a huge 600-year-old Buddha carved from one hunk of jade. One of the most sacred statues in Asia.

(Emerald Buddha at Wat Phra Kaew, Image by J. P. Swimmer, Wikimedia Commons)

Vietnam, where U.S. soldiers filled the streets. Everyone knew a very ugly and different war was coming.

Calcutta. Knight got sick immediately. He thinks food poisoning. He was sure, for one whole day, that he was going to die. He rallied. He ended up at the Ganges. There was a funeral. Others were bathing. Others were drinking the same water.

“The Upanishads say,Lead me from the unreal to the real.” So Knight went to Kathmandu and hiked up the Himalayas.

Back to India. Bombay.

Kenya. Giant ostriches tried to outrun the bus, records Knight. When Masai warriors boarded the bus, a baboon or two would also try to board.

Cairo. The Giza plateau. Standing besides desert nomads with their silk-draped camels. At the foot of the Great Sphinx.

…The sun hammered down on my head, the same sun that hammered down on the thousands of men who built these pyramids, and the millions of visitors who came after. Not one of them was remembered, I thought. All is vanity, says the Bible. All is now, says Zen. All is dust, says the desert.

(Great Sphinx of Giza,Photo by Johnny 201, Wikimedia Commons)

Then Jerusalem.

…the first century rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah said our work is the holiest part of us. All are proud of their craft. God speaks of his work; how much more should man.

Istanbul. Turkish coffee. Lost on the confusing streets of the Bosphorus. Glowing minarets. Then the golden labyrinths of Topkapi Palace.

Rome. Tons of pasta. And the most beautiful women and shoes he’d ever seen, says Knight. The Coliseum. The Vatican. The Sistine Chapel.

Florence. Reading Dante. Milan. Da Vinci: One of his obsessions was the human foot, which he called a masterpiece of engineering.

Venice. Marco Polo. The palazzo of Robert Browning: “If you get simply beauty and naught else, you get about the best thing God invents.”

Paris. The Pantheon. Rousseau. Voltaire: “Love truth, but pardon error.” Praying at Notre Dame. Lost in the Louvre.

(The Louvre,Photo by Pipiten, Wikimedia Commons)

Then to where Joyce slept, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Walking down the Seine, and stopping where Hemingway and Dos Passos read the New Testament aloud to each other.

Next, up the Champs-Elysees, along the liberators’ path, thinking of Patton: “Don’t tell people how to do things, tell them what to do and let them surprise you with their results.”

Munich. Berlin. East Berlin:

…I looked around, all directions. Nothing. No trees, no stores, no life. I thought of all the poverty I’d seen in every corner of Asia. This was a different kind of poverty, more willful, somehow, more preventable. I saw three children playing in the street. I walked over, took their picture. Two boys and a girl, eight years old. The girl – red wool hat, pink coat – smiled directly at me. Will I ever forget her? Or her shoes? They were made of cardboard.

Vienna. Stalin, Trotsky, Tito, Hitler, Jung, Freud. All at the same location in the same time period. A “coffee-scented crossroads.” Where Mozart walked. Crossing the Danube. The spires of St. Stephen’s Church, where Beethoven realized he was deaf.

London. Buckingham Palace, Speakers’ Corner, Harrods.

Knight asked himself what the highlight of his trip was.

Greece, I thought. No question. Greece.

…I meditated on that moment, looking up at those astonishing columns, experiencing that bracing shock, the kind you receive from all great beauty, but mixed with a powerful sense of – recognition?

Was it only my imagination? After all, I was standing at the birthplace of Western civilization. Maybe I merely wanted it to be familiar. But I don’t think so. I had the clearest thought: I’ve been here before.

Then, walking up those bleached steps, another thought: This is where it all begins.

On my left was the Parthenon, which Plato had watched the teams of architects and workmen build. On my right was the Temple of Athena Nike. Twenty-five centuries ago, per my guidebook, it had housed a beautiful frieze of the goddess Athena, thought to be the bringer of “nike,” or victory.

It was one of many blessings Athena bestowed. She also rewarded the dealmakers. In the Oresteia she says: ‘I admire… the eyes of persuasion.’ She was, in a sense, the patron saint of negotiators.

(Temple of Athena Nike, Photo by Steve Swayne, Wikimedia Commons)

1963

When Buck got home, his hair was to his shoulders and his beard three inches long. It had been four months since meeting with Onitsuka. But they hadn’t sent the sample shoes. Knight wrote to them to ask why. They wrote back, “Shoes coming… In a little more days.”

Knight got a haircut and shaved. He was back. His father suggested he speak with his old friend, Don Frisbee, CEO of Pacific Power & Light. Frisbee had an MBA from Harvard. Frisbee told Buck to get his CPA while he was young, a relatively conservative way to put a floor under his earnings. Knight liked that idea. He had to take three more courses in accounting, first, which he promptly did at Portland State.

Then Knight worked at Lybrand, Ross Bros. & Montgomery. It was a Big Eight national firm, but its Portland office was small. $500 a month and some solid experience. But pretty boring.

1964

Finally, twelve pairs of shoes arrived from Onitsuka. They were beautiful, writes Knight. He sent two pairs immediately to his old track coach at Oregon, Bill Bowerman.

Bowerman was a genius coach, a master motivator, a natural leader of young men, and there was one piece of gear he deemed crucial to their development. Shoes.

Bowerman was obsessed with shoes. He constantly took his runners’ shoes and experimented on them. He especially wanted to make the shoes lighter. One ounce over a mile is fifty pounds.

Bowerman would try anything. Kangaroo. Cod. Knight says four or five runners on the team were Bowerman’s guinea pigs. But Knight was his “pet project.”

It’s possible that everything I did in those days was motivated by some deep yearning to impress, to please, Bowerman. Besides my father there was no man whose approval I craved more, and besides my father there was no man who gave it less often. Frugality carried over to every part of the coach’s makeup. He weighed and hoarded words of praise, like uncut diamonds.

After you’d won a race, if you were lucky, Bowerman might say: ‘Nice race.’ (In fact, that’s precisely what he said to one of his milers after the young man became one of the very first to crack the mythical four-minute mark in the United States.) More likely Bowerman would say nothing. He’d stand before you in his tweed blazer and ratty sweater vest, his string tie blowing in the wind, his battered ball cap pulled low, and nod once. Maybe stare. Those ice-blue eyes, which missed nothing, gave nothing. Everyone talked about Bowerman’s dashing good looks, his retro crew cut, his ramrod posture and planed jawline, but what always got me was that gaze of pure violet blue.

(Statue of Bill Bowerman, Photo by Diane Lee Jackson, Wikimedia Commons)

For his service in World War II, Bowerman received the Silver Star and four Bronze Stars. Bowerman eventually became the most famous track coach in America. But he hated being called “coach,” writes Knight. He called himself, “Professor of Competitive Responses” because he viewed himself as preparing his athletes for the many struggles and competitions that lay ahead in life.

Knight did his best to please Bowerman. Even so, Bowerman would often lose patience with Knight. On one occasion, Knight told Bowerman he was coming down with the flu and wouldn’t be able to practice. Bowerman told him to get his ass out there. The team had a time trial that day. Knight was close to tears. But he kept his composure and ran one of his best times of the year. Bowerman gave him a nod afterward.

Bowerman suggested meeting for lunch shortly after seeing the Tiger shoes from Onitsuka. At lunch, Bowerman told Knight the shoes were pretty good and suggested they become business partners. Knight was shocked.

Had God himself spoken from the whirlwind and asked to be my partner, I wouldn’t have been more surprised.

Knight and Bowerman signed an agreement soon thereafter. Knight found himself thinking again about his coach’s eccentricities.

…He always went against the grain. Always. For example, he was the first college coach in America to emphasize rest, to place as much value on recovery as on work. But when he worked you, brother, he worked you. Bowerman’s strategy for running the mile was simple. Set a fast pace for the first two laps, run the third as hard as you can, then triple your speed on the fourth. There was a Zen-like quality to this strategy because it was impossible. And yet it worked. Bowerman coached more sub-four-minute milers than anybody, ever.

Knight wrote Onitsuka and ordered three hundred pairs of shoes, which would cost $1,ooo. Buck had to ask his dad for another loan, who asked him, “Buck, how long do you think you’re going to keep jackassing around with these shoes?” His father told him he didn’t send him to Oregon and Stanford to be a door-to-door shoe salesman.

At this point, Knight’s mother told him she wanted to purchase a pair of Tigers. This helped convince Knight’s father to give him another loan.

In April 1964, Knight got the shipment of Tigers. Also, Mr. Miyazaki told him he could be the distributor for Onitsuka in the West. Knight quit his accounting job to focus on selling shoes that spring. His dad was horrified, his mom happy, remarks Knight.

After being rejected by a couple of sporting goods stores, Knight decided to travel around to various track meets in the Pacific Northwest. Between races, he’d talk with the coaches, the runners, the fans. He couldn’t write the orders fast enough. Knight wondered how this was possible, given his inability to sell encyclopedias.

…So why was selling shoes so different? Because, I realized, it wasn’t selling. I believed in running. I believed that if people got out and ran a few miles every day, the world would be a better place, and I believed these shoes were better to run in. People, sensing my belief, wanted some of that belief for themselves.

Belief, I decided. Belief is irresistable.

(Illustration by Lkeskinen0)

Knight started the mail order business because he started getting letters from folks wanting Tigers. To help the process along, he mailed some handouts with big type:

‘Best news in flats! Japan challenges European track shoe domination! Low Japanese labor costs make it possible for an exciting new firm to offer these shoes at the low, low price of $6.95.’ [Note: This is close to $54 in 2018 dollars, due to inflation.]

Knight had sold out his first shipment by July 4, 1964. So he ordered 900 more. This would cost $3,000. His dad grudgingly gave him a letter of guarantee, which Buck took to the First National Bank of Oregon. They approved the loan.

Knight wondered how to sell in California. He couldn’t afford airfare. So every other weekend, he’d stuff a duffel bag with Tigers. He’d don his army uniform and head to the local air base. The MPs would wave him on to the next military transport to San Francisco or Los Angeles.

When in Los Angeles, he’d save more money by staying with a friend from Stanford, Chuck Cale. At a meet at Occidental College, a handsome guy approached Knight, introducing himself as Jeff Johnson. He was a fellow runner whom Knight had run with and against while at Stanford. At this point, Johnson was studying anthropology and planning on becoming a social worker. But he was selling shoes – Adidas then – on weekends. Knight tried to recruit him to sell Tigers instead. No, because he was getting married and needed stability, responded Johnson.

Then Knight got a letter from a high school wrestling coach in Manhasset, New York, claiming that Onitsuka had named him the exclusive distributor for Tigers in the United States. He ordered Knight to stop selling Tigers.

Knight contacted his cousin, Doug Houser, who’d recently graduated from Stanford Law School. Houser found out Mr. Manhasset was a bit of a celebrity, a model who was one of the original Marlboro Men. Knight: “Just what I need. A pissing match with some mythic American cowboy.”

Knight went into a funk for awhile. Then he decided to go visit Onitsuka in Japan. Knight bought a new suit and also a book,How to Do Business with the Japanese.

Knight realized he had to remain cool. Emotion could be fatal.

The art of competition, I’d learned from track, was the art of forgetting, and now I reminded myself of that fact. You must forget your limits. You must forget your doubts, your pain, your past. You must forget that internal voice screaming, begging, ‘Not one more step!’ And when it’s not possible to forget it, you must negotiate with it. I thought over all the races in which my mind wanted one thing, and my body wanted another, those laps in which I’d had to tell my body, ‘Yes, you raise some excellent points, but let’s keep going anyway…’

After finding a place to stay in Kobe, Knight called Onitsuka and requested a meeting. He got a call back saying Mr. Miyazaki no longer worked there. Mr. Morimoto had replaced him, and didn’t want Knight to visit headquarters. Mr. Morimoto would meet him for tea. None of this was good.

At the meeting, Knight layed out the arguments. They had had an agreement. He also pointed out the very robust sales Blue Ribbon had had thus far. He dropped the name of his business partner. Mr. Morimoto, who was about Knight’s age, said he’d get back to him.

Knight thought it was over. But then he got a call from Morimoto saying, “Mr. Onitsuka…himself… wishes to see you.”

At this meeting, Knight first presented his arguments again to those who were initially present. Then Mr. Onitsuka arrived.

Dressed in a dark blue Italian suit, with a head of black hair as thick as shag carpet, he filled every man in the conference room with fear. He seemed oblivious, however. For all his power, for all his wealth, his movements were deferential… Morimoto tried to summarize my reasons for being there. Mr. Onitsuka raised a hand, cut him off.

Without preamble, he launched into a long, passionate monologue. Some time ago, he’d said, he’d had a vision. A wondrous glimpse of the future. ‘Everyone in the world wear athletic shoes all the time,’ he said. ‘I know this day will come.’ He paused, looking around the table at each person, to see if they also knew. His gaze rested on me. He smiled. I smiled. He blinked twice. ‘You remind me of myself when I am young,’ he said softly. His stared into my eyes. One second. Two. Now he turned his gaze to Morimoto. ‘This about those thirteen western states?’ he said. ‘Yes,’ Morimoto said. ‘Hm,’ Onitsuka said. ‘Hmmmm.’ He narrowed his eyes, looked down. He seemed to be meditating. Again he looked up at me. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Alright. You have western states.’

Knight ordered $3,400 worth of shoes [about $26,000 in 2018 dollars].

(Mount Fuji, Photo by Wipark Kulnirandorn)

To celebrate, Knight decided to climb to the top of Mount Fuji. Buck met a girl on the wap up, Sarah, who was studying philosophy at Connecticut College for Women. It went well for a time. Many letters back and forth. A couple of visits. But she decided Knight wasn’t “sophisticated” enough. Jeanne, one of Buck’s younger sisters, found the letters, read them, and told Buck, “You’re better off without her.” Buck then asked his sister – given her interest in mail – if she’d like to help with the mail order business for $1.50 an hour. Sure. Blue Ribbon Employee Number One.

1965

Buck got a letter from Johnson. He’d bought some Tigers and loved them. Could he become a commissioned salesman for Blue Ribbon? Sure. $1.75 for each pair of running shoes, $2 for spikes, were the commissions.

Then the letters from Johnson kept coming:

I liked his energy, of course. And it was hard to fault his enthusiasm. But I began to worry he might have too much of each. With the twentieth letter, or the twenty-fifth, I began to worry that the man might be unhinged. I wondered why everything was so breathless. I wondered if he was ever going to run out of things he urgently needed to tell me, or ask me…

…He wrote to say that he wanted to expand his sales territory beyond California, to include Arizona, and possibly New Mexico. He wrote to suggest that we open a retail store in Los Angeles. He wrote to tell me that he was considering placing ads in running magazines and what did I think? He wrote to inform me that he’d placed those ads in running magazines and the response was good. He wrote to ask why I hadn’t answered any of his previous letters. He wrote to plead for encouragement. He wrote to complain that I hadn’t responded to his previous plea for encouragement.

I’d always considered myself a conscientious correspondent… And I always meant to answer Johnson’s letters. But before I got around to it, there was always another one, waiting. Something about the sheer volume of his correspondence stopped me…

Eventually Johnson realized he loved shoes and running more than anthropology or social work.

(Monk meditating, Photo by Ittipon)

In his heart of hearts Johnson believed that runners are God’s chosen, that running, done right, in the correct spirit and with the proper form, is a mystical exercise, no less than meditation or prayer, and thus he felt called to help runners reach their nirvana. I’d been around runners much of my life, but this kind of dewy romanticism was something I’d never encountered. Not even the Yahweh of running, Bowerman, was as pious about the sport as Blue Ribbon’s Part-Time Employee Number Two.

In fact, in 1965, running wasn’t even a sport. It wasn’t popular, it wan’t unpopular, it just was. To go out for a three-mile run was something weirdos did, presumably to burn off manic energy. Running for exercise, running for pleasure, running for endorphins, running to live better and longer – these things were unheard of.

People often went out of their way to mock runners. Drivers would slow down and honk their horns. ‘Get a horse!,’ they’d yell, throwing a beer or soda at the runner’s head. Johnson had been drenched by many a Pepsi. He wanted to change all this…

Above all, he wanted to make a living doing it, which was next to impossible in 1965. In me, in Blue Ribbon, he thought he saw a way.

I did everything I could to discourage Johnson from thinking like this. At every turn, I tried to dampen his enthusiasm for me and my company. Besides not writing back, I never phoned, never visited, never invited him to Oregon. I also never missed an opportunity to tell him the unvarnished truth. I put it flatly: ‘Though our growth has been good, I owe First National Bank of Oregon $11,000… Cash flow is negative.’

He wrote back immediately, asking if he could work for me full-time…

Knight just shook his head. Finally in last summer of 1965, Knight accepted Johnson’s offer. Johnson had been making $460 as a social worker, so he proposed $400 a month [over $3,000 a month in 2018 dollars]. Knight very reluctantly agreed. It seemed like a huge sum. Knight writes:

As ever, the accountant in me saw the risk, the entrepreneur the possibility. So I split the difference and kept moving forward.

Knight then forgot about Johnson because he had bigger issues. Blue Ribbon had doubled its sales in one year. But Knight’s banker said they were growing too fast for their equity. Knight asked how doubling sales – profitably – can be a bad thing.

In those days, however, commercial banks were quite different from investment banks. Commercial banks never wanted you to outgrow your cash balance. Knight tried to explain that growing sales as much as possible – profitably – was essential to convince Onitsuka to stick with Blue Ribbon. And then there’s the monster, Adidas. But his banker kept repeating:

‘Mr. Knight, you need to slow down. You don’t have enough equity for this kind of growth.’

Knight kept hearing the word “equity” in his head over and over. “Cash,” that’s what it meant. But he was deliberately reinvesting every dollar – on a profitable basis. What was the problem?

Every meeting with his banker, Knight managed to hold his tongue and say nothing, basically agreeing. Then he’d keep doubling his orders from Onitsuka.

Knight’s banker, Harry White, had essentially inherited the account. Previously, Ken Curry was Knight’s banker, but Curry bailed when Knight’s father wouldn’t guarantee the account in the case of business failure.

Furthermore, the fixation on equity didn’t come from White, but from White’s boss, Bob Wallace. Wallace wanted to be the next president of the bank. Credit risks were the main roadblock to that goal.

Oregon was smaller back then. First National and U.S. Bank were the only banks, and the second one had already turned Blue Ribbon down. So Knight didn’t have a choice. Also, there as no such thing as venture capital in 1965.

(First National Bank of Oregon, Photo by Steve Morgan, Wikimedia Commons)

To make matters worse, Onitsuka was always late in its shipments, no matter how much Knight pleaded with them.

By this point, Knight had passed the four parts of the CPA exam. So he decided to get a job as an accountant. He invested a good chunk of his paycheck into Blue Ribbon.

In analyzing companies as an accountant, Knight learned how they sold things or didn’t, how they survived or didn’t. He learned how companies got into trouble and how they got out.

It was while working for the Portland branch of Price Waterhouse that he met Delbert J. Hayes, who was the best accountant in the office. Knight describes Hayes as a man with “great talent, great wit, great passions – and great appetites.” Hayes was six-foot-two and three hundred pounds. He loved food and alcohol. And he smoked two packs a day.

Hayes looked at numbers the way a poet looks at clouds or a geologist looks at rocks, says Knight. He could see the beauty of numbers. Numbers were a secret code.

Every evening, Hayes would insist on taking junior accountants out for a drink. Hayes would talk nonstop, like he drank. But while other accountants dismissed Hayes’ stories, Knight always paid careful attention. In every tale told by Hayes was some piece of wisdom about business. So Knight would match Hayes, shot for shot, in order to learn as much as he could.

The following morning, Knight was always sick. But he willed himself to do the work. Being in the Army Reserves at the same time wasn’t easy. Meanwhile, the conflict in Vietnam was heating up. Knight:

I had grown to hate that war. Not simply because I felt it was wrong. I also felt it was stupid, wasteful. I hated stupidity. I hated waste. Above all, that war, more than other wars, seemed to be run along the same principles of my bank. Fight not to win, but to avoid losing. A surefire losing strategy.

Hayes came to appreciate Knight. Hayes thought it was a tough time to launch a new company with zero cash balance. But he did acknowledge that having Bowerman as a partner was a valuable, intangible asset.

Recently, Bowerman and Mrs. Bowerman had visited Onitsuka and charmed everyone. Mr. Onitsuka told Bowerman about founding his shoe company in the rubble after World War II.

He’d built his first lasts, for a line of basketball shoes, by pouring hot wax from Buddhist candles over his own feet. Though the basketball shoes didn’t sell, Mr. Onitsuka didn’t give up. He simply switched to running shoes, and the rest is shoe history. Every Japanese runner in the 1964 Games, Bowerman told me, was wearing Tigers.

Mr. Onitsuka also told Bowerman that the inspiration for the unique soles on Tigers had come to him while eating sushi. Looking down at his wooden platter, at the underside of an octopus’s leg, he thought a similar suction cup might work on the sole of a runner’s flat. Bowerman filed that away. Inspiration, he learned, can come from quotidian things. Things you might eat. Or find lying around the house.

Bowerman started corresponding not only with Mr. Onitsuka, but with the entire production team at the Onitsuka factory. Bowerman realized that Americans tend to be longer and heavier than the Japanese. He thought the Tigers could be modified to fit Americans better. Most of Bowerman’s letters went unanswered, but like Johnson Bowerman just kept writing more.

Eventually he broke through. Onitsuka made prototypes that conformed to Bowerman’s vision of a more American shoe. Soft inner sole, more arch support, heel wedge to reduce stress on the Achilles tendon – they sent the prototype to Bowerman and he went wild for it. He asked for more.

Bowerman also experimented with drinks to help his runners recover. He invented an early version of Gatorade. As well, he conducted experiments to make the track softer. He invented an early version of polyurethane.

1966

Johnson kept inundating Knight with long letters, including a boatload of parenthetical comments and a list of PS’s. Knight felt he didn’t have time to send the requested words of encouragement. Also, it wasn’t his style.

I look back now and wonder if I was truly being myself, or if I was emulating Bowerman, or my father, or both. Was I adopting their man-of-few-words demeanor? Was I maybe modeling all the men I admired? At the time I was reading everything I could get my hands on about generals, samurai, shoguns, along with biographies of my three main heroes – Churchill, Kennedy, and Tolstoi. I had no love of violence, but I was fascinated by leadership, or lack thereof, under extreme conditions…

I wasn’t that unique. Throughout history men have looked to the warrior for a model of Hemingway’s cardinal virtue, pressurized grace… One lesson I took from all my home-schooling about heroes was that they didn’t say much. None was a blabbermouth. None micromanaged. “Don’t tell people how to do things, tell them what to do and let them surprise you with their results.”

(Winston Churchill in 1944, Wikimedia Commons)

Johnson never let Knight’s lack of communication discourage him. Johnson was full of energy, passion, and creativity. He was going all-out, seven days a week, to sell Blue Ribbon shoes. Johnson had an index card for each customer including their shoe sizes and preferences. He sent all of them birthday cards and Christmas cards. Johnson developed extensive correspondence with hundreds of customers.

Johnson began aggregating customer feedback on the shoes.

…One man, for instance, complained that Tiger flats didn’t have enough cushion. He wanted to run the Boston Marathon but didn’t think the Tigers would last the twenty-six miles. So Johnson hired a local cobbler to graft rubber soles from a pair of shower shoes into a pair of Tiger flats. Voila. Johnsn’s Frankenstein flat had space-age, full-length, midsole cushioning. (Today it’s standard in all training shoes for runners.) The jerry-rigged Johnson sole was so dynamic, so soft, so new, Johnson’s customer posted a personal best in the Boston. Johnson forwarded me the results and urged me to pass them along to Tiger. Bowerman had just asked me to do the same with his batch of notes a few weeks earlier. Good grief, I thought, one mad genius at a time.

Johnson had customers in thirty-seven states. Knight meant to warn him about encroaching on Malboro Man’s territory. But he never got around to it.

Knight did write to tell Johnson that if he could sell 3,250 shoes by the end of June 1966, then he could open the retail outlet he’d been asking about. Knight calculated that 3,250 was impossible, so he wasn’t too worried.

Somehow Johnson hit 3,250. So Blue Ribbon opened its first retail store in Santa Monica.

He then set about turning the store into a mecca, a holy of holies for runners. He bought the most comfortable chairs he could find, and afford (yard sales), and he created a beautiful space for runners to hang out and talk. He built shelves and filled them with books that every runner should read, many of them first editions from his own library. He covered the walls with photos of Tiger-shod runners, and laid in a supply of silk-screened T-shirts withTiger across the front, which he handed out to his best customers. He also stuck Tigers to a black lacquered wall and illuminated them with a strip of can lights – very hip. Very mod. In all the world, there had never been a sanctuary for runners, a place that didn’t just sell them shoes but celebrated them and their shoes. Johnson, the aspiring cult leader of runners, finally had his church. Services were Monday through Saturday, nine to six.

When he first wrote me about the store, I thought of the temples and shrines I’d seen in Asia, and I was anxious to see how Johnson’s compared. But there just wasn’t time…

Knight got a heads up that the Marlboro man had just launched an advertising campaign which involved poaching customers of Blue Ribbon. So Knight flew down to see Johnson.

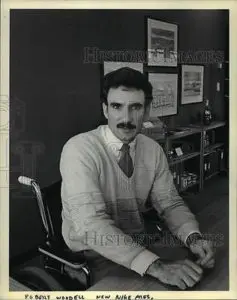

(Jeff Johnson, Employee Number One)

Johnson’s apartment was one giant running shoe. There were running shoes seemingly everywhere. And there were many books – mostly thick volumes on philosophy, religion, sociology, anthropology, and classics in Western literature. Knight had thought he liked to read. This was a new level, says Knight.

Johnson told Knight he had to go visit Onitsuka again. Johnson started typing notes, ideas, lists, which would become a manifesto for Knight to take to Onitsuka. Knight wired Onitsuka. They got back to him, but it wasn’t Morimoto. It was a new guy, Kitami.

Knight told Kitami and other executives about the performance of Blue Ribbon thus far, virtually doubling sales each year and projecting more of the same. Kitami said they wanted someone more established, with offices on the East Coast. Knight replied that Blue Ribbon had offices on the East Coast and could handle national distribution. “Well,” said Kitami, “this changes things.”

The next morning, Kitami awarded Blue Ribbon exclusive distribution rights for the United States. A three-year contract. Knight promptly placed an order for 5,000 more shoes, which would cost $20,000 – more than $150,000 in 2018 dollars – that he didn’t have. Kitami said he would ship them to Blue Ribbon’s East Coast office.

There was only one person crazy enough to move to the East Coast on a moment’s notice….

1967

Knight delayed telling Johnson. Then he hired John Bork, a high school track coach and a friend of a friend, to run the Santa Monica store. Bork showed up at the store and told Johnson that he, Bork, was the new boss so that Johnson could go back east.

Johnson called Knight. Knight told him he’d had to tell Onitsuka that Blue Ribbon had an east coast office. A huge shipment was due to arrive at this office. Johnson was the only one who could manage the east coast store. The fate of the company was on his shoulders. Johnson was shocked, then mad, then freaked out. Knight flew down to visit him.

Johnson talked himself into going to the east coast.

The forgiveness Johnson showed me, the overall good nature he demonstrated, filled me with gratitude, and a new fondness for the man. And perhaps a deeper loyalty. I regretted my treatment of him. All those unanswered letters. There are team players, I thought, and then there are team players, and then there’s Johnson.

Soon thereafter, Bowerman called asking Knight to add a new employee – Geoff Hollister. A former track guy. Full-time Employee Number Three.

Then Bowerman called again with yet another employee – Bob Woodell.

I knew the name, of course. Everyone in Oregon knew the name. Woodell had been a standout on Bowerman’s 1965 team. Not quite a star, but a gritty and inspiring competitor. With Oregon defending its second national championship in three years, Woodell had come out of nowhere and won the long jump against vaunted UCLA. I’d been there, I’d watched him do it, and I’d come away mighty impressed.

The very next day, during a celebration, there had been an accident. The float twenty guys were carrying collapsed after someone lost their footing. It landed on Woodell and crushed one of his vertebra, paralyzing his legs.

Knight called Woodell. Knight realized it was best to keep it strictly business. So he told Woodell that Bowerman had recommended him. Would he like to grab lunch to discuss the possibility of working for Blue Ribbon? Sure thing, he said.

Woodell had already mastered a special car, a Mercury Cougar with hand controls. At lunch, they hit it off and Woodell impressed Knight.

I wasn’t certain what Blue Ribbon was, or if it would ever become a thing at all, but whatever it was or might become, I hoped it would have something of this man’s spirit.

Knight offered Woodell a job opening a second retail store, in Eugene, for a monthly salary of $400. Woodell immediately agreed. They shook hands. “He still hand the strong grip of an athlete.”

(Bob Woodell 1967)

Bowerman’s latest experiment was with the Spring Up. He noticed the outer sole melted, whereas the midsole remained solid. He convinced Onitsuka to fuse the outer sole to the midsole. The result looked like the ultimate distance training shoe. Onitsuka also accepted Bowerman’s suggestion of a name for the shoe, the “Aztec,” in homage to the upcoming 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Unfortunately, Adidas had a similar name for one of its shoes and threatened to sue. So Bowerman changed the name to “Cortez.”

The situation with Adidas reminded Knight of when he had been a runner in high school. The fastest runner in the state was Jim Grelle (pronounced “Grella”) and Knight had been second-fastest. So Knight spent many races staring at Grelle’s back. Then they both went to Oregon, so Knight spent more years staring at Grelle’s back.

Adidas made Knight think of Grelle. Knight felt super motivated.

Once again, in my quixotic effort to overtake a superior opponent, I had Bowerman as my coach. Once again he was doing everything he could to put me in position to win. I often drew on the memory of his old prerace pep talks, especially when we were up against our blood rivals, Oregon State. I would replay Bowerman’s epic speeches… Nearly sixty years later it gives me chills to recall his words, his tone. No one could get your blood going like Bowerman, though he never raised his voice.

Thanks to the Cortez, Blue Ribbon finished the year strong. They had nearly doubled their sales again, to $84,000. Knight rented an office for $50 a month. And he transferring Woodell to the “home office.” Woodell had shown himself to be highly skilled and energetic, and in particular, he was excellent at organizing.

The office was cold and the floor was warped. But it was cheap. Knight built a corkboard wall, pinning up different Tiger models and borrowing some of Johnson’s ideas from the Santa Monica store.

Knight thought perhaps he could save even more money by living at his office. Then he reflected that living at your office was what a crazy person does. Then he got a letter from Johnson saying he was living at his office. Johnson had set up shop in Wellesley, a suburb of Boston.

Johnson told Knight how he had chosen the location. He’d seen people running along country roads, many of them women. Ali MacGraw look-alikes. Sold.

1968

Knight:

I wanted to dedicate every minute of every day to Blue Ribbon… I wanted to be present, always. I wanted to focus constantly on the one task that really mattered. If my life was to be all work and no play, I wanted my work to be play. I wanted to quit Price Waterhouse. Not that I hated it; it just wasn’t me.

I wanted what everyone wants. To be me, full-time.

Even though Blue Ribbon was on track to double sales again, there was never enough cash, certainly not to pay Knight. Knight found another job he thought might fit better with his desire to focus as much as possible on Blue Ribbon. Assistant Professor of Accounting at Portland State University.

Knight, a CPA who had worked for two accounting firms, knew accounting pretty well at this point. But he was restless and twitchy, with several nervous tics – including wrapping rubber banks around his wrist and snapping them. One of his students was named Penelope Parks. Knight was captivated by her.

Knight decided to use the Socratic method to teach accounting. Miss Parks turned out to be the best student in the class. Soon thereafter, Miss Parks asked if Knight would be her advisor. Knight then asked her if she’d like a job for Blue Ribbon to help with bookkeeping. “Okay.”

On Miss Parks’ first day at Blue Ribbon, Woodell gave her a list of things – typing, bookkeeping, scheduling, stocking, filing invoices – and told her to pick two. Hours later, she’d done every thing on the list. Within a week, Woodell and Knight couldn’t remember how they’d gotten by without her, recalls Knight.

Furthermore, Miss Parks was “all-in” with respect to the mission of Blue Ribbon. She was good with people, too. She had a healing effect on Woodell, who was still struggling to adjust to his legs being paralyzed.

Knight often volunteered to go get lunch for the three of them. But his head was usually so full of business matters that he would invariably get the orders mixed up. “Can’t wait to see what I’m eating for lunch today,” Woodell might say quietly. Miss Parks would hide a smile.

Later on, Knight found out that Miss Parks and Woodell weren’t cashing any of their paychecks. They truly believed in Blue Ribbon. It was more than just a job for them.

Knight and Penny started dating. They were good at communicating nonverbally since they were both shy people. They were a good match and eventually decided to get married. Knight felt like she was a partner in life.

Knight made another trip to Onitsuka. Kitami was very friendly this time, inviting him to the company’s annual picnic.Knight met a man named Fujimoto at the picnic. It turned out to be another life-altering partnership.

…I was doing business with a country I’d come to love. Gone was the initial fear. I connected with the shyness of the Japanese people, with the simplicity of their culture and products and arts. I liked that they tried to add beauty to every part of life, from the tea ceremony to the commode. I liked that the radio announced each day which cherry trees, on which corner, were blossoming, and how much.

(Cherry trees in Japan, Photo by Nathapon Triratanachat)

1969

Knight was able to hire more ex-runners on commission. Sales in 1968 had been $150,000 and now they were on track for $300,000 for 1969.

Knight was finally able to pay himself a salary. But before leaving Portland State, he happened to see a starving artist in the hallway and asked if she’d do advertising art part-time. Her name was Carolyn Davidson, and she said OK.

Bowerman and Knight were losing trust in Kitami. Bowerman thought he didn’t know much about shoes and was full of himself. Knight hired Fujimoto to be a spy. Knight pondered again that when it came to business in Japan, you never knew what a competitor or a partner would do.

Knight was absentminded. He couldn’t go to the store and return with the one thing Penny asked for. He misplaced wallets and keys frequently. And he was constantly bumping into trees, poles, and fenders while driving.

Knight got in the habit of calling his father in the evening. His father would be in his recliner, while Buck would be in his. They’d hash things over.

Woodell and Knight began looking for a new office. They started enjoying hanging out together. Before parting, Knight would time Woodell on how fast he could fold up his wheelchair and get it and himself into his car.

Woodell was super positive and super energetic, a constant reminder of the importance of good spirits and a great attitude.

Buck and Penny would have Woodell over for dinner. Those were fun times. They would take turns describing what the company was and might be, and what it must never be. Woodell was always dressed carefully and always had on a pair of Tigers.

Knight asked Woodell to become operations manager. He’d demonstrated already that he was exceptionally good at managing day-to-day tasks. Woodell was delighted.

1970

Knight visited Onitsuka again. He discovered that Kitami was being promoted to operations manager. Onitsuka and Blue Ribbon signed another 3-year agreement. Knight looked into Kitami’s eyes and noticed something very cold. Knight never forgot that cold look.

Knight pondered the fact that the shipments from Onitsuka were always late, and sometimes had the wrong sizes or even the wrong models. Woodell and Knight discovered that Onitsuka always filled its orders from Japanese companies first, and then sent its foreign exports.

Meanwhile, Wallace at the bank kept making things difficult. Knight concluded that a small public offerings could create the extra cash Blue Ribbon needed. At the time, in 1970, a few venture capital firms had been launched. But they were in California and mostly invested in high-tech. So Knight formed Sports-Tek, Inc., as a holding company for Blue Ribbon. They tried a small public offering. It didn’t work.

Friends and family chipped in. Woodell’s parents were particularly generous.

On June 15, 1970, Knight was shocked to see a Man of Oregon on the cover ofSports Illustrated. His name was Steve Prefontaine. He’d already set a national record in high school at the two-mile (8:41). In 1970, he’d run three miles in 13:12.8, the fastest time on the planet.

Knight learned from aFortune magazine about Japan’s hyper-aggressive sosa shoga, “trading companies.” It was hard to see what these trading companies were exactly. Sometimes they were importers. Sometimes they were exporters. Sometimes they were banks. Sometimes they were an arm of the government.

After being harangued by Wallace at First National about cash balances again, Knight walked out and saw a sign for the Bank of Tokyo. He was escorted to a back room, where a man appeared after a couple of minutes. Knight showed the man his financials and said he needed credit. The man said that Japan’s sixth-largest trading company had an office at the top floor of this same building. Nissho Iwai was a $100-billion dollar company.

Knight met a man named Cam Murakami, who offered Knight a deal on the spot. Knight said he had to check with Onitsuka first. Knight wired Kitami, but heard nothing back at all for weeks.

Then Knight got a call from a guy on the east coast who told him that Onitsuka had approached him about becoming its new U.S. distributor. Knight checked with Fujimoto, his spy. Yes, it was true. Onitsuka was considering a clean break with Blue Ribbon.

Knight invited Kitami to visit Blue Ribbon.

1971

March 1971. Kitami was on his way. Blue Ribbon vowed to give him the time of his life.

Kitami arrived with a personal assistant, Hiraku Iwano, who was just a kid. At one point, Kitami told Knight that Blue Ribbon’s sales were disappointing. Knight said sales were doubling every year. “Should be triple some people say,” Kitami replied. “What people?”, asked Knight. “Never mind,” answered Kitami.

Kitami took a folder from his briefcase and repeated the charge. Knight tried to defend Blue Ribbon. Back and forth. Kitami had to use the restroom. When he left the meeting room, Knight looked into Kitami’s briefcase and tried to snag the folder that he thought Kitami had been referring to.

Kitami went back to his hotel. Knight still had the folder. He and Woodell opened it up. They found a list of eighteen U.S. athletic shoe distributors. These were the “some people” who told Kitami that Blue Ribbon wasn’t performing well enough.

I was outraged, of course. But mostly hurt. For seven years we’d devoted ourselves to Tiger shoes. We’d introduced them to America, we’d reinvented the line. Bowerman and Johnson had shown Onitsuka how to make a better shoe, and their designs were now foundational, setting sales records, changing the face of the industry – and this was how we were repaid?

At the end of Kitami’s visit, as planned, there was dinner with Bowerman, Mrs. Bowerman, and his friend (and lawyer), Jaqua. Mrs. Bowerman usually didn’t allow alcohol, but she was making an exception. Knight and Kitami both liked mai tais, which were being served.

Unfortunately, Bowerman had a few too many mai tais. It appeared things might get out of hand. Knight looked at Jaqua, remembering that he’d been a fighter pilot in World World II, and that his wingman, one of his closest friends, had been shot out of the sky by a Japanese Zero. Knight thought he sensed something starting to erupt in Jaqua.

Kitami, however, was having a great time. Then he found a guiter. He started playing it and singing a country Western. Suddenly, he sang “O Sole Mio.”

A Japanese businessman, strumming a Western guitar, singing an Italian ballad, in the voice of an Irish tenor. It was surreal, then a few miles past surreal, and it didn’t stop. I’d never know there were so many verses to “O Sole Mio.” I’d never known a roomful of active, restless Oregonians could sit still and quite for so long. When he set down the guitar, we all tried not to make eye contact with each other as we gave him a big hand. I clapped and clapped and it all made sense. For Kitami, this trip to the United States – the visit to the bank, the meetings with me, the dinner with the Bowermans – wasn’t about Blue Ribbon. Nor was it about Onitsuka. Like everything else, it was all about Kitami.

At a meeting soon thereafter, however, Kitami told Knight that Onitsuka wanted to buy Blue Ribbon. If Blue Ribbon did not accept, Onitsuka would have to work with other distributors. Knight knew he still needed Onitsuka, at least for awhile. So he thought of a stall. He told Kitami he’d have to talk with Bowerman. Kitami said OK and left.

Knight sent the budget and forecast to First National. White informed Knight at a meeting that First National would no longer be Blue Ribbon’s bank. White was sick about it, the bank officers were divided, but it had been Wallace’s call. Knight strove straight to U.S. Bank. Sorry. No.

Blue Ribbon was finishing 1971 with $1.3 million in sales, but it was in danger of failing. Fortunately, Bank of Cal gave Blue Ribbon a small line of credit.

Knight went back to Nissho and met Tom Sumeragi. Sumeragi told Knight that Nissho was willing to take a second position to their banks. Also, Nissho had sent a delegation to Onitsuka to try to work out a deal on financing. Onitsuka had tossed them out. Nissho was embarrased that a $25 million company had thrown out a $100 billion company. Sumeragi told Knight that Nissho could introduce him to other shoe manufacturers in Japan.

Knight knew he had to find a new shoe factory somewhere. He found one in Gaudalajara, Mexico. Knight placed an order for three thousand soccer shoes. It’s at this point that Knight asked his part-time artist, Carolyn Davidson, to try to design a logo. “Something that evokes a sense of motion.” She came back two weeks later and her sketches had a theme. But Knight was wondering what the theme was, “…fat lightning bolts? Chubby check marks? Morbidly obese squiggles?…”

Davidson returned later. Same theme, but better. Woodell, Johnson, and a few others liked it, saying it looked like a wing or a whoosh of air. Knight wasn’t thrilled about it, but went along because they were out of time and had to send it to the factory in Mexico.

(Nike logo, Timidonfire, Wikimedia Commons)

They also needed a name. Falcon. Dimension Six. These were possibilities they’d come up with. Knight liked Dimension Six mostly because he’d come up with it. Everyone told him it was awful. It didn’t mean anything. Bengal. Condor. They debated possibilities.

It was time to decide. Knight still didn’t know. Then Woodell told him that Johnson had had a dream and then woke up with the name clearly in mind: “Nike.”

Knight reminisced… “The Greek goddess of victory. The Acropolis. The Parthenon. The Temple…”

Knight had to decide. He hated having to decide under time pressure. He’s not sure if it was luck or spirit or something else, but he chose “Nike.” Woodell said, “Hm.” Knight replied, “Yeah, I know. Maybe it’ll grow on us.”

(Nike logo, Wikimedia Commons)

Meanwhile, Nissho was infusing Blue Ribbon with cash. But Knight wanted a more permanent solution. He conceived of a public offering of convertible debentures. People bought them, including Knight’s friend Cale.

The factory in Mexico didn’t produce good shoes. Knight talked with Sumeragi, who knew a great deal about shoe factories around the world. Sumeragi also offered to introduce Knight to Jonas Senter, “a shoe dog.”

Shoe dogs were people who devoted themselves wholly to the making, selling, buying, or designing of shoes. Lifers used the phrase cheerfully to describe other lifers, men and women who had toiled so long and hard in the shoe trade, they thought and talked about nothing else. It was an all-consuming mania… But I understood. The average person takes seventy-five hundred steps a day, 274 million steps over the course of a long life, the equivalent of six times around the globe – shoe dogs, it seemed to me, simply wanted to be part of that journey. Shoes were their way of connecting with humanity…

Senter was the “knockoff king.” He’d been behind a recent flood of knockoff Adidas. Senter’s protege was a guy named Sole.

Knight wasn’t sure partnering with Nissho was the best move. Jaqua suggested Knight meet with his brother-in-law, Chuck Robinson, CEO of Marcona Mining, which had many joint ventures. Each of the big eight Japanese trading firms was a partner in at least one of Marcona’s mines, records Knight. Chuck to Buck: “If the Japanese trading company understands the rules from the first day, they will be the best partners you’ll ever have.”

Knight went to Sumeragi and said: “No equity in my company. Ever.” Sumeragi consulted a few folks, came back and said: “No problem. But here’s our deal. We take four percent off the top, as a markup on product. And market interest rates on top of that.” Done.

Knight met Sole, who mentioned five factories in Japan.

A bit later, Bowerman was eating breakfast when he noticed the waffle iron’s gridded pattern. This gave him an idea and he started experimenting.

…he took a sheet of stainless steel and punched it with holes, creating a waffle-like surface, and brought this back to the rubber company. The mold they made from that steel sheet was pliable, workable, and Bowerman now had two foot-sized squares of hard rubber nubs, which he brought home and sewed to the sole of a pair of running shoes. He gave these to one of his runners. The runner laced them on and ran like a rabbit.

Bowerman phoned me, excited, and told me about his experiment. He wanted me to send a sample of his waffle-soled shoes to one of my new factories. Of course, I said. I’d send it right away – to Nippon Rubber.

I look back over decades and see him toiling in his workshop, Mrs. Bowerman carefully helping, and I get goosebumps. He was Edison in Menlo Park, Da Vinci in Florence, Tesla in Wardenclyffe. Divinely inspired. I wonder if he knew, if he had any clue, that he was the Daedalus of sneakers, that he was making history, remaking an industry, transforming the way athletes would run and stop and jump for generations. I wonder if he could conceive in that moment all he’d done. All that would follow.

1972

The National Sporting Goods Association Show in Chicago in 1972 was extremely important for Blue Ribbon because they were going to introduce the world to Nike shoes. If sales reps liked Nike shoes, Blue Ribbon had a chance to flourish. If not, Blue Ribbon wouldn’t be back in 1973.

Right before the show, Onitsuka announced its “acquisition” of Blue Ribbon. Knight had to reassure Sumeragi that there was no acquisition. At the same time, Knight couldn’t break from Onitsuka just yet.

As Woodell and Johnson prepared the booth – with stacks of Tigers and also with stacks of Nikes – they realized the Nikes from Nippon Rubber weren’t as high-quality as the Tigers. The swooshes were crooked, too.

Darn it, this was no time to be introducing flawed shoes. Worse, we had to push these flawed shoes on to people who weren’t our kind of people. They were salesmen. They talked like salesmen, walked like salesmen, and they dressed like salesmen – tight polyester shirts, Sansabelt slacks. They were extroverts, we were introverts. They didn’t get us, we didn’t get them, and yet our future depended on them. And now we’d have to persuade them, somehow, that this Nike thing was worth their time and trust – and money.

I was on the verge of losing it, right on the verge. Then I saw Johnson and Woodell were already losing it, and I realized that I couldn’t afford to… ‘Look fellas, this is the worst the shoes will ever be. They’ll get better. So if we can just sell these… we’ll be on our way.’

The salesmen were skeptical and full of questions about the Nikes. But by the end of the day, Blue Ribbon had exceeded its highest expectations. Nikes had been the smash hit of the show.

Johnson was so perplexed that he demanded an answer from the representative of one his biggest accounts. The rep explained:

‘We’ve been doing business with you Blue Ribbon guys for years and we know that you guys tell the truth. Everyone else bullshits, you guys always shoot straight. So if you say this new shoe, this Nike, is worth a shot, we believe.’

Johnson came back to the booth and said, “Telling the truth. Who knew?” Woodell laughed. Johnson laughed. Knight laughed.

Two weeks later, Kitami showed up without warning in Knight’s office, asking about “this… NEE-kay.” Knight had been rehearsing for this situation. He replied simply that it was a side project just in case Onitsuka drops Blue Ribbon. Kitami seemed placated.

Kitami asked if the Nikes were in stores. No, said Knight. Kitami asked when Blue Ribbon was going to sell to Onitsuka. Knight answered that he still needed to talk with Bowerman. Kitami then said he had business in California, but would be back.

Knight called Bork in Los Angeles and told him to hide the Nikes. Bork hid them in the back of the store. But Kitami, when visiting the store, told Bork he had to use the bathroom. While in the back, Kitami found stacks of Nikes.

Bork called Knight and told him, “Jig’s up… It’s over.” Bork ended up quitting. Knight discovered later that Bork had a new job… working for Kitami.

Kitami demanded a meeting. Bowerman, Jaqua, and Knight were in attendance. Jaqua told Knight to say nothing no matter what. Jaqua told Kitami that he hoped something could still be worked out, since a lawsuit would be damaging to both companies.

Knight called a company-wide meeting to explain that Onitsuka had cut them off. Many people felt resigned, says Knight, in part because there was a recession in the United States. Gas lines, political gridlock, rising unemployment, Vietnam. Knight saw the discouragement in the faces of Blue Ribbon employees, so he told them:

‘…This is the moment we’ve been waiting for. One moment. No more selling someone else’s brand. No more working for someone else. Onitsuka has been holding us down for years. Their late deliveries, their mixed-up orders, their refusal to hear and implement our design ideas – who among us isn’t sick of dealing with all that? It’s time we faced facts: If we’re going to succeed, or fail, we should do so on our own terms, with our own ideas – our own brand. We posted two million in sales last year… none of which had anything to do with Onitsuka. That number was a testament to our ingenuity and hard work. Let’s not look at this as a crisis. Let’s look at this as our liberation. Our Independence Day.’

Johnson told Knight, “Your finest hour.” Knight replied he was just telling the truth.

The Olympic track-and-field trials in 1972 were going to be in Eugene. Blue Ribbon gave Nikes to anyone who would take them. And they handed out Nike T-shirts left and right.

The main event was on the final day, a race between Steve Prefontaine – known as “Pre” – and the great Olympian George Young. Pre was the biggest thing to hit American track and field since Jesse Owens. Knight tried to figure out why. It was hard to say, exactly. Knight:

Sometimes I thought the secret to Pre’s appeal was his passion. He didn’t care if he died crossing the finish line, so long as he crossed first. No matter what Bowerman told him, no matter what his body told him, Pre refused to slow down, ease off. He pushed himself to the brink and beyond. This was often a counterproductive strategy, and sometimes it was plainly stupid, and occasionally it was suicidal. But it was always uplifting for the crowd. No matter the sport – no matter the human endeavor, really – total effort will win people’s hearts.

(Steve Prefontaine)

Gerry Lindgren was also in this race with Pre and Young. Lindgren may have been the best distance runner in the world at that time. Lindgren had beaten Pre when Lindgren was a senior and Pre a freshman.

Pre took the lead right away. Young tucked in behind him. In no time they pulled way ahead of the field and it became a two-man affair… Each man’s strategy was clear. Young meant to stay with Pre until the final lap, then use his superior sprint to go by and win. Pre, meanwhile, intended to set such a fast pace at the outset that by the time they got to that final lap, Young’s legs would be gone.

For eleven laps they ran a half stride apart. With the crowd now roaring, frothing, shrieking, the two men entered the final lap. It felt like a boxing match. It felt like a joust… Pre reached down, found another level – we saw him do it. He opened up a yard lead, then two, then five. We saw Young grimacing and we knew that he would not, could not, catch Pre. I told myself, Don’t forget this. Do not forget. I told myself there was much to be learned from such a display of passion, whether you were running a mile or a company.

Both men had broken the American record. Pre had broken it by a little bit more.

…What followed was one of the greatest ovations I’ve ever heard, and I’ve spent my life in stadiums.

I’d never witnessed anything quite like that race. And yet I didn’t just witness it. I took part in it. Days later I felt sore in the hams and quads. This, I decided, this is what sports are, what they can do. Like books, sports give people a sense of having lived other lives, of taking part in other people’s victories. And defeats. When sports are at their best, the spirit of the fan merges with the spirit of the athlete, and in that convergence, in that transference, is the oneness that mystics talk about.

1973

Bowerman had retired from coaching, partly because of the sadness of the terrorist attacks at the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Bowerman had been able to help hide one Israeli athlete. Bowerman had immediately called the U.S. consul and shouted, “Send the marines!” Eleven Israeli athletes had been captured and later killed. An unspeakable tragedy. Knight thought of the deaths of the two Kennedys, and Dr. King, and the students at Kent State.

Ours was a difficult, death-drenched age, and at least once every day you were forced to ask yourself: What’s the point?

Although Bowerman had retired from coaching, he was still coaching Pre. Pre had finished a disappointing fourth at the Olympics. He could have gotten silver if he’d allowed another runner to be the front runner and if he’d coasted in his wake. But, of course, Pre couldn’t do that.

It took Pre six months to re-emerge. He won the NCAA three-mile for a fourth straight year, with a time of 13:05.3. He also won in the 5,000 by a good margin with a time of 13:22.4, a new American record. And Bowerman had finally convinced Pre to wear Nikes.

At that time, Olympic athletes couldn’t receive endorsement money. So Pre sometimes tended bar and occasionally ran in Europe in exchange for illicit cash from promoters.

Knight decided to hire Pre, partly to keep him from injuring himself by racing too much. Pre’s title was National Director of Public Affairs. People often asked Knight what that meant. Knight would say, “It means he can run fast.” Pre wore Nikes everywhere and he preached Nike as gospel, says Knight.

Around this time, Knight realized that Johnson was becoming an excellent designer. The East Coast was running smoothly, but needed reorganization. So Knight asked Johnson to switch places with Woodell. Woodell excelled at operations and thus would be a great fit for the East Coast situation.

Although Johnson and Woodell irritated one another, they both denied it. When Knight asked them to switch places, the two exchanged house keys without the slightest complaint.

In the spring of 1973, Knight held his second meeting with the debenture holders. He had to tell them that despite $3.2 million in sales, the company had lost $57,000. The reaction was negative. Knight tried to explain that sales continue to explode higher. But the investors were not happy.

Knight left the meeting thinking he would never, ever take the company public. He didn’t want to deal with that much negativity and rejection ever again.

Onitsuka filed suit against Blue Ribbon in Japan. So Blue Ribbon had to file against them in the United States.

Knight asked his Cousin Houser to be in charge of the case. Houser was a fine lawyer who carried himself with confidence.

Better yet, he was a tenacious competitor. When we were kids Cousin Houser and I used to play vicious, marathon games of badminton in his backyard. One summer we played exactly 116 games. Why 116? Because Cousin Houser beat me 115 straight times. I refused to quit until I’d won. And he had no trouble understanding my position.

More importantly, Cousin Houser was able to talk his firm into taking the Blue Ribbon case on contingency.

Knight continued his evening conversations with this father, who believed strongly in Blue Ribbon’s cause. Knight’s father, who had been trained as a lawyer, spent time studying law books. He reassured Buck, “we” are going to win. This support from his father boosted Buck’s spirits at a challenging time.

(Law library, Photo by Spiroview Inc.)

Cousin Houser told Knight one day that he was bringing on a new member of the team, a young lawyer from UC Berkeley School of Law, Rob Strasser. Not only was Strasser brilliant. He also believed in the rightness of Blue Ribbon’s case, viewing it as a “holy crusade.”

Strasser was a fellow Oregonian who felt looked down on by folks north and south. Moreover, he felt like an outcast. Knight could relate. Strasser often downplayed his intelligence for fear of alienating people. Knight could relate to that, too.

Intelligence like Strasser’s, however, couldn’t be hidden for long. He was one of the greatest thinkers I ever met. Debator, negotiator, talker, seeker – his mind was always whirring, trying to understand.

When he wasn’t preparing for the trial, Knight was exclusively focused on sales. It was essential that they sell out every pair of shoes in each order. The company was still growing fast and cash was always short.

Whenever there was a delay, Woodell always knew what the problem was and could quickly let Knight know. Knight on Woodell:

He had a superb talent for underplaying the bad, and underplaying the good, for simply being in the moment… throughout the day a steady rain of pigeon poop would fall on Woodell’s hair, shoulders, desktop. But Woodell would simply dust himself off, casually clear his desk with the side of his hand, and continue with his work.

…I tried often to emulate Woodell’s Zen monk demeanor. Most days, however, it was beyond me…