You’re deluding yourself. I’m deluding myself. Our brains just do this automatically, all the time. We invent simple stories based on cause and effect. Often this is harmless. But sometimes it’s important to recognize that reality is far more unpredictable than we’d like.

We’re not wired to understand probabilities. As Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have demonstrated, even many professional statisticians are not good “intuitive statisticians.” They’re usually only good if they slow down and work through the problem at hand step-by-step. Otherwise, they too tend to create overly simplistic, overly deterministic stories.

(Photo by Wittayayut Seethong)

To develop better mental habits, a good place to start is by recognizingdelusions andbiases, which are widespread in business, politics, and economics. To that end, here are fourof the best books:

- Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), by Daniel Kahneman

- Poor Charlie’s Almanack (Walsworth, 3rd edition, 2005), by Charles T. Munger

- The Halo Effect…and Eight Other Business Delusions That Deceive Managers (Free Press, 2007), by Phil Rosenzweig

- Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? (Princeton University Press, 2006), by Philip Tetlock

Tetlock’s work is particularly important. He tracked over 27,000 predictions made in real time by 284 experts from 1984 to 2003. Tetlock found that the expert predictions–on the whole–were no better than chance. Many of these experts have deep historical knowledge of politics or economics, which can give us important insights and is often a precursor to scientific knowledge. But it’s not yet science–the ability to make predictions.

Kahneman and Munger both show how our intuition uses mental shortcuts (heuristics) to jump to conclusions. Often these conclusions are fine. But not if probabilistic reasoning is needed to reach a good decision.

- Here’s a summary of Kahneman’s work:https://boolefund.com/cognitive-biases/

- Here’s a summary of Munger’s work:https://boolefund.com/the-psychology-of-misjudgment/

This blog post focuses on Rosenzweig’s book, which examinesdelusions in business, with particular emphasis onthe Halo Effect.

Outline for this blog post:

- The Halo Effect

- Illusions and Delusions

- How Little We Know

- The Story of Cisco

- Up and Down with ABB

- Halos All Around Us

- Research to the Rescue?

- Searching for Stars, Finding Halos

- The Mother of All Business Questions,Take Two

- Managing Without Coconut Headsets

THE HALO EFFECT

Rosenzweig quotes John Kay of theFinancial Times:

The power of the halo effect means that when things are going well praise spills over to every aspect of performance, but also that when the wheel of fortune spins, the reappraisal is equally extensive. Our search for excessively simple explanations, our desire to find great men and excellent companies, gets in the way of the complex truth.

(Image by Ileezhun)

Rosenzweig explains the essence of the Halo Effect:

If you select companies on the basis of outcomes–whether success or failure–and then gather data that are biased by those outcomes, you’ll never know what drives performance. You’ll only know how high performers or low performers are described.

Rosenzweig describes his book as “a guide for the reflective manager,” a way to avoid delusions and to think critically. It’s quite natural for us to construct simple stories about why things happen. But many events–including business success and failure–don’t happen in a straightforward way. There’s a large measure of uncertainty (chance) involved.

Rosenzweig adds:

Of course, for those who want a book that promises to reveal the secret of success, or the formula to dominate their market, or the six steps to greatness, there are plenty to choose from. Every year, dozens of new books claim to reveal the secrets of leading companies… Others tell you how to become an innovation powerhouse, or craft a failsafe strategy, or devise a boundaryless organization, or make the competition irrelevant.

But if anything, the world is getting more unpredictable:

In fact, for all the secrets and formulas, for all the self-proclaimed thought leadership, success in business is as elusive as ever. It’s probably more elusive than ever, with increasingly global competition and technological change moving at faster and faster rates–which might explain why we’re tempted by promises of breakthroughs and secrets and quick fixes in the first place. Desperate circumstances push us to look for miracle cures.

Rosenzweig explains that business managers are under great pressure to increase profits. So they naturally look for clear solutions that they can implement right away. Business writers and experts are happy to supply what is demanded. However, reality is usually far more unpredictable than is commonly assumed.

ILLUSIONS AND DELUSIONS

Science is the ability to predict things: if x, then y (with probability z). (If we’re talking about physics–other than quantum mechanics–then z = 100% in the vast majority of cases.) But the sciences that deal with human behavior still haven’t discovered enough to make many predictions. There are specific experiments or circumstances where good predictions can be made–such as where to place specific items in a retailer to maximize sales. And good research has uncovered numerous statistical correlations.

But on the whole, there’s still much unpredictability in business and in human behavior generally. There’s still not much scientific knowledge.

Rosenzweig says some of the biggest recent business blockbusters contain several delusions:

For all their claims of scientific rigor, for all their lengthy descriptions of apparently solid and careful research, they operate mainly at the level of storytelling. They offer tales of inspiration that we find comforting and satisfying, but they’re based on shaky thinking. They’re deluded.

Rosenzweig explains that most management books seek to understand what leads to high performance. By contrast, Rosenzweig asks why it is so difficult to understand high performance. We suffer from many delusions. Our intuition leads us to construct simple stories to explain things, even when those stories are false.

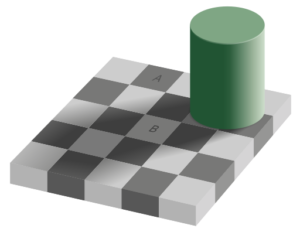

(Image by Edward H. Adelson, via Wikimedia commons)

Look at squares A and B just above: Are they the same color? Or is one square lighter than the other?

A and B are exactly the same color. However, our visual system automatically uses contrast. If it didn’t, then as Steven Pinker has pointed out, we would think a lump of coal in bright sunlight was white. We would think a lump of snow inside a dark house was black. We don’t make these mistakes because our visual system works in part by contrast. Kathryn Schulz mentions this in her excellent book,Being Wrong (HarperCollins, 2010).

This use of contrast is a heuristic–a shortcut–used by our visual system. This happens automatically. And usually this heuristic helps us, as in Pinker’s examples.

The important point is that our intuition (part of our mental system) islike our visual system. Our intuitionalso uses heuristics.

- If we are asked a difficult question, our intuition substitutes an easier question and then answers that question. This happens automatically and without our conscious awareness.

- Similarly, our intuition constructs simple stories in terms of cause and effect, even if reality is far more complex and random. This happens automatically and without our conscious awareness.

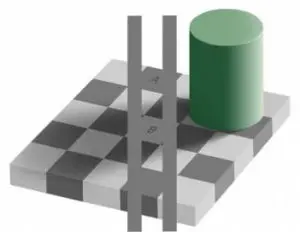

(Image by Edward H. Adelson, via Wikimedia Commons)

This second image is the same as the previous one–except this one has two vertical grey bars. This helps (to some extent) our eyes to see that squares A and B are exactly the same color.

Rosenzweig mentions that some rigorous research of business has been conducted. But this research often reaches far more modest conclusions than what we seek. As a result, it’s not popular or well-known. For instance, there may be a 0.2 correlation between certain approaches of a CEO and business performance. That’s a huge finding–20% of business performance is based on specific CEO behavior.

But that means 80% of business performance is due to other factors, including chance. That’s not the type of information people in business want to hear when they’re busy and under pressure.

HOW LITTLE WE KNOW

In January 2004, after a disastrous holiday season, Lego–the Danish toymaker–fired its chief operating officer, Poul Ploughman. Rosenzweig points out that when a company does well, we tend to automatically think its leaders did the right things and should be praised or promoted. When a company does poorly, we tend to jump to the conclusion that its leaders did the wrong things and should be replaced.

But reality is far more complex. Good leadership may represent 20-30% of the reason a company is doing well now, but luck may be an even bigger factor. Similarly, bad leadership may be responsible for 20-30% of a company’s poor performance, whereas bad luck–unforeseeable events–may be a bigger factor.

(Photo by Marco Clarizia)

As humans, we’re driven to construct stories in which success and failure are completely explainable–without reference to luck–based on the actions of people and systems. This satisfies our psychological need to see the world as a predictable place.

However, reality is unpredictable to an extent. We understand far less than we think. Luck usually plays a large role in business success and failure.

When Lego hired Ploughman, it was seen as a coup. Ploughman helped Lego expand into electronic toys. When the initial results of this expansion were not positive, Lego’s CEO Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen lost patience and fired Ploughman.

The business press reported that Lego had “strayed from its core.” However, the company tried to expand because its traditional operations were not as profitable as before. If the company’s attempted expansion had been more profitable, the business press would have reported that Lego “wisely expanded.”

(Photo of lego bricks by Benjamin D. Esham)

When it comes to business performance, there are many factors–including luck. A company may move forward on an absolute basis, but fall behind relative to competitors. Also, consumer tastes are unpredictable.

- A company may attempt expansion and fail, but the decision may have been wise based on available information. Regardless, observers are likely to say the company “unwisely strayed from its core.”

- Or a company may try to expand and succeed, but it may have been a stupid decision based on available information. Regardless, observers are likely to claim that the company “brilliantly expanded.”

To understand better how businesses succeed, we should try to understand what factors are involved in good decisions, even though good decisions often don’t work and bad decisions sometimes do. We want to avoidoutcome bias, where our evaluation of the quality of a decision is colored by whether the result was favorable or not.

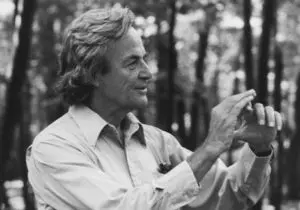

Science is: if x, then y (with probability z).This is a slightly modified definition (I added “with probability z”) Rosenzweig borrowed from physicist Richard Feynman.

In some areas of business, scientists have discovered reliable statistical correlations. For instance, this set of behaviors–a, b, and c–has a 0.10 correlation with revenues. If you do a, b, and c–holding all else constant–then revenues will increase approximately 10%.

The difficult thing about studying business is that often you cannot run controlled experiments. Of course, sometimes you can. For instance, you can experiment with where to place various items in a store (or chain of stores). You can compare results and gain good statistical information. Also, there are promotions and advertising campaigns that you can test. And you can track consumer behavior online.

But frequently you cannot run controlled experiments. As Rosenzweig observes, you can’t do 100 acquisitions, and manage half of them one way, the other half another way, and then compare the results.

There’s nothing wrong withstories, which are satisfying explanations we construct about various events. But stories are not science, and it’s important to keep the distinction straight, especially when we’re trying to understand why things happen.

An even better term thanpseudo-science is Feynman’s term,Cargo Cult Science. Rosenzweig quotes Feynman:

In the South Seas, there is a cult of people. During the war, they saw airplanes land with lots of materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas–he’s the controller–and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

(Photo of Richard Feynman in 1984, by Tamiko Thiel)

Rosenzweig concludes:

The business world is full of Cargo Cult Science, books and articles that claim to be rigorous scientific research but operate mainly at the level of storytelling. In later chapters, we’ll look at some of this research–some that meet the standard of science but aren’t satisfying as stories, and some that offer wonderful stories but are doubtful as science. As we’ll see, some of the most successful business books of recent years, perched atop the bestseller list for months on end, cloak themselves in the mantle of science, but have little more predictive power than a pair of coconut headsets on a tropical island.

It’s not that stories have nothing to teach us. For instance, experts may develop deep historical knowledge that offers us useful insights into human behavior. And such knowledge is often an antecedent to scientific knowledge.

But we have to be careful not to confuse stories with science. Otherwise, it’s very easy and natural to delude ourselves that we understand something scientifically, when in fact we don’t. Our intuition creates simple stories of cause and effect just as automatically as our visual system is unable to avoid optical illusions.

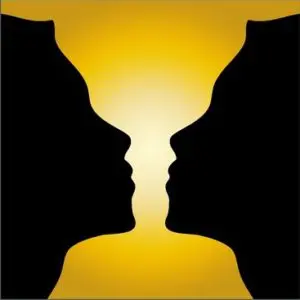

(Holy grail or two girls, by Micka)

THE STORY OF CISCO

Rosenzweig tells the story of Cisco. Sandra K. Lerner and Leonard Bosack met in graduate school, fell in love, and got married. After graduating, they each took jobs managing computer networks at different corners of the Stanford campus. They wanted to communicate, and they invented a multiprotocol router. Rosenzweig:

Like many start-ups, Cisco began by operating out of a basement and at first sold its wares to friends and professional acquaintances. Once revenues approached $1 million, Lerner and Bosack went in search of venture capital. The man who finally said yes was Donald Valentine at Sequoia Capital, the seventy-seventh moneyman they approached, who invested $2.5 million for a third of the stock and management control. Valentine began to professionalize Cisco’s management, bringing in as CEO an industry veteran, John Morgridge. Sales grew rapidly, from $1.5 million in 1987 to $28 million in 1989, and in February 1990, Cisco went public.

Valentine and Morgridge brought on John Chambers as a sales executive in 1991. Chambers had worked at IBM and Wang Labs, and was ready to work at a smaller company where he might have more of an impact. Chambers came up with a plan for Cisco to dominate the market for computer infrastructure. Over the next three years, Cisco acquired two dozen companies.

(Cisco Logo, via Wikimedia Commons)

Chambers became CEO in 1995 and Cisco continued acquiring companies. Cisco’s revenues reached $4 billion in 1997. Rosenzweig:

Cisco rode the crest of the internet wave in 1998… Cisco had a 40 percent share of the $20 billion data-networking equipment industry–routers, hubs, and devices that made up the so-called plumbing of the Internet–and a massive 80 percent share of the high-end router market. But Cisco wasn’t just growing revenues. It was profitable, too. At a time when even the most admired Internet start-ups, like Amazon.com, were losing money, Cisco posted operating margins of 60 percent. This wasn’t some dot-com with a business plan, way out there in the blue, riding on a smile and a shoeshine. It wasn’t panning for Internet gold, it was selling picks and shovels to miners who were lining up around the corner to buy them…

Cisco reached $100 billion market capitalization in just twelve years. It had taken Microsoft twenty years (the previous record).

Accounts explaining Cisco’s success nearly always gave credit to John Chambers. He’d overcome dyslexia to go to law school. And Chambers said he learned from working at IBM and Wang that if you don’t react to shifts in technology, your work will be lost and the lives of employees disrupted. Cisco wouldn’t make that mistake, Chambers declared.

Cisco had a disciplined, detailed process for making acquisitions, and an even more disciplined process for integrating acquisitions into Cisco’s operations. Cisco had made “a science” of acquisitions. And it cared a lot about the human side–turnover rate for acquired employees was only 2.1% versus an industry average of 20%.

After the Internet stock bubble burst, business reporters completely reversed their opinion of Cisco on every major point:

- Customer service–from excellent to poor

- Forecasting ability–from outstanding to terrible

- Innovation–from nearly perfect to visibly flawed

- Acquisitions–from scientific process to binge buying

- Senior leadership–from amazing to arrogant

Business reporters recalled that Chambers had claimed that Cisco “was faster, smarter, and just plain better than competitors.” Rosenzweig says this is fascinating because only business reporters had said this when Cisco was doing well. Chambers himself never said it, but now business writers seemed to recall that he had.

Rosenzweig points out that it was possible that Cisco had changed. But that’s not what business reporters were saying. They viewed Cisco through an entirely different lens, now that the company was struggling.

The essence of the Halo Effect: If a company is performing well, then it’s easy to view virtually everything it does through a positive lens. If a company is doing poorly, then it’s natural to view virtually everything it does through a negative lens. The story of Cisco certainly fits this pattern.

As Rosenzweig remarks, the fundamental problem is twofold:

- We have little scientific knowledge of what leads to business success or failure.

- But we do know about revenues, profits, and the stock price. If these observable measures are positive, we intuitively jump to the conclusion that the company must be doing many things well. If these observable measures are declining, we conclude that the company must be doing many things poorly.

UP AND DOWN WITH ABB

ABB is a Swedish-Swiss industrial company that was created in 1988 by the merger of two leading engineering companies, Sweden’s ASEA and Switzerland’s Brown Boveri.

(ABB Logo, via Wikimedia Commons)

Rosenzweig thought it would be interesting to look at a non-American, non-Internet company. The Halo Effect is still clearly visible in the accounts of ABB’s rise and fall.

When it came to ABB’s rise, from the late 1980’s to the late 1990’s, we see that business experts drew similar conclusions. First, the CEO, Percy Barnevik, was widely and highly praised. Rosenzweig describes Barnevik as a “Scandinavian who combined old world manners and language skills with American pragmatism and an orientation for action.” Barnevik was described in the press as very driven, but also unpretentious and accessible. He met frequently with all levels of ABB management. He was a speed reader and highly analytical. Away from work, he climbed mountains and went for long jogs (lasting up to 10 hours). On top of all this, Barnevik was viewed as humble, not arrogant.By 1993, Barnevik had become a legend.

Another explanation for ABB’s success was its culture. Despite its conservative Swedish and Swiss roots, ABB had a strong bias for action. Barnevik said so on several occasions, asserting that the only unacceptable thing was to do nothing. He claimed that if you do 50 things, and 35 are in the right direction, that is enough.

A third explanation was that the company was designed to be globally efficient, but still able to compete in local markets. Barnevik wanted people in different locations to be able to launch new products, make design changes, or alter production methods. ABB had a matrix structure, with fifty-one business areas and forty-one country managers. This resulted in 5,000 profit centers, with each one empowered to achieve high performance and accountable to do so.

In 1996, ABB was named Europe’sMost Respected Company for the third year in a row by theFinancial Times. Kevin Barham and Claudia Heimer, of Ashridge Management Centre in England, published a 382-page book about ABB. They identified five reasons for ABB’s success: customer focus, connectivity, communication, collegiality, and convergence. They placed ABB in the same category as Microsoft and General Electric.

In 1997, Barnevik stepped down as CEO, replaced by Goran Lindahl. Then the company transitioned towards businesses based on intellectual capital. ABB entered new areas, like financial services. It exited the trains and trams business, as well as the nuclear fuels business. Rosensweig asks if ABB was “straying from its core.” Not at all because ABB was still seen as a success. Lindahl was CEO of the year in 1999 according to the American publication,Industry Week. Lindahl was the first European to get this award.

In November 2000, Lindahl abruptly stepped down, saying he wanted to be replaced by someone with more expertise in IT. J¼rgen Centerman became the new CEO.

ABB’s performance entered a steep decline. Centerman was replaced by J¼rgen Dormann in September 2002. Dormann sold the company’s petrochemicals business and its structured finance business. ABB focused on automation technologies and power technologies. But the company’s market cap dipped below $4 billion, down from a peak of $40 billion.

When ABB was on the rise in terms of performance, it was described as bold and daring because of its bias for action and experimentation. Now, with performance being poor, ABB was described as impulsive and foolish. Moreover, whereas ABB’s decentralized strategy had been praised when ABB was rising, now the same strategy was criticized. As for Barnevik, while he had previously been described as bold and visionary, now he was called arrogant and imperial.

Most interesting of all, notes Rosenzweig, is that neither the company nor Barnevik was thought to have changed. It was only how they were characterized that had changed–clear examples of the Halo Effect.

Rosenzweig writes:

…one of the main reasons we love stories is that they don’t simply report disconnected facts but make connections about cause and effect, often ascribing credit or blame to individuals. Our most compelling stories often place people at the center of events… Once widely revered, Percy Barnevik was now an exemplar of arrogance, of greed, of bad leadership.

HALOS ALL AROUND US

During World War I, the American psychologist Edward Thorndike studied how superiors rated their subordinates. Thorndike noticed that good soldiers were good on nearly every attribute, whereas underperforming soldiers were bad on nearly every attribute. Rosenzweig comments:

It was as if officers figured that a soldier who was handsome and had good posture should also be able to shoot straight, polish his shoes well, and play the harmonica, too.

Thorndike called this the Halo Effect. Rosenzweig:

There are a few kinds of Halo Effect. One refers to what Thorndike observed, a tendency to make inferences about specific traits on the basis of a general impression. It’s difficult for most people to independently measure separate features; there’s a common tendency to blend them together. The Halo Effect is a way for the mind to create and maintain a coherent and consistent picture, to reduce cognitive dissonance.

(Image by Aliaksandra Molash)

Rosenzweig gives the example of George W. Bush. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, Bush’s approval ratings rose sharply, not surprisingly as the public rallied behind him. But Bush’s ratings on other factors, such as his management of the economy, also rose significantly. There was no logical reason to think Bush’s handling of the economy was suddenly much better after the attacks. This is an instance of the Halo Effect.

By October 2005, the situation had reversed. Support for the Iraq War waned, and people were upset about the government response to Hurricane Katrina. Bush’s overall ratings were at 37 percent. His rating was also lower in every individual category.

Rosenzweig then explains another kind of Halo Effect:

…the Halo Effect is not just a way to reduce cognitive dissonance. It’s also a heuristic, a sort of rule of thumb that people use to make guesses about things that are hard to assess directly. We tend to grasp information that is relevant, tangible, and appears to be objective, and then make attributions about other features that are more vague or ambiguous.

Rosenzweig later adds:

All of which helps explain what we saw at Cisco and ABB. As long as Cisco was growing and profitable and setting records for its share price, managers and journalists and professors inferred that it had a wonderful ability to listen to its customers, a cohesive corporate culture, and a brilliant strategy. And when the bubble burst, observers were quick to make the opposite attribution. It all made sense. It told a coherent story. Same for ABB, where rising sales and profits led to favorable evaluations of its organization structure, its risk-taking culture, and most clearly the man at the top–and then to unfavorable evaluations when performance fell.

Rosenzweig recounts an experiment by professor Barry Staw. Various groups of people were asked to forecast future sales and earnings based on a set of financial data. Then some groups were told they’d done a good job, while other groups were told the opposite. But this was doneat random, completely independent of actual performance.

Later, each group was asked about how it had functioned as a group. Groups that had been told that they did well on their forecasts reported that their group had been cohesive, with good communication, openness to change, and good motivation. Groups that had been told that they didn’t do well on their forecasts reported that they lacked cohesion, had poor communication, and were unmotivated.

Staw’s experiment is a clear demonstration of the Halo Effect.

- If people believe that a group is effective–irrespective of whether the group can be measured as such–then they attribute one set of characteristics to it.

- If people believe that a group is ineffective–irrespective of whether the group can be measured as such–then they attribute the opposite set of characteristics to it.

This doesn’t mean that cohesiveness, motivation, etc., is unimportant for group communication. Rather, it means that people typically cannot assess these types of qualities with much (or any) objectivity, especially if they already have a belief about how a given group has performed in some task.

When it’s hard to measure something objectively, people tend to look for something that is objective and use that as a heuristic, inferring that harder-to-measure attributes must be similar to whatever is objective (like financial peformance).

As yet another example, Rosenzweig mentions that IBM’s employees were viewed as smart, creative, and hardworking in 1984 when IBM was doing well. In 1992, after IBM had faltered, the same people were described as complacent and bureauratic.

As we’ve seen, the Halo Effect is particularly frequent when people try to judge how good a leader is. Just as we don’t have much scientific knowledge for how a company can succeed, we also don’t have much scientific knowledge about what makes a good leader. Experts, when they look at a company that is doing well, tend to think that the leader has many good qualities such as courage, clear vision, and integrity. When the same experts examine a company that is doing poorly, they tend to conclude that the leader lacks courage, vision, and integrity.This happens even when experts are looking at the same company and that company is doing the same things.

(Image by Kirsty Pargeter)

When Microsoft was doing well, Bill Gates was described as ambitious, brilliant, and visionary. When Microsoft appeared to falter in 2001, after Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ordered Microsoft to be broken up, Bill Gates was described as arrogant and stubborn.

Rosenzweig gives two more examples: Fortune’s World’s Most Admired Companies, and the Great Places to Work Institute’sBest Companies to Work For index. Both lists appear to be significantly impacted by the Halo Effect. Companies that have been doing well financially tend to be viewed and described much more favorably on a range of metrics.

Rosenzweig closes the chapter by noting that the Halo Effect is the most basic delusion, but that there are several more delusions he will examine in the coming chapters.

RESEARCH TO THE RESCUE?

Rosenzweig:

The Halo Effect shapes how we commonly talk about so many topics in business, from decision processes to people to leadership and more. It shows up in our everyday conversations and in newspaper and magazine articles. It affects case studies and large-sample surveys. It’s not so much the result of conscious distortion as it is a natural human tendency to make judgments about things that are abstract and ambiguous on the basis of other things that are salient and seemingly objective. The Halo Effect is just too strong, the desire to tell a coherent story too great, the tendency to jump on bandwagons too appealing.

The most fundamental business question is:

What leads to high business performance?

The Halo Effect is far from inevitable, despite being very common. There are researchers who use careful statistical tests to isolate the effects of independent variables on dependent variables.

The dependent variables relate to company performance. And we have good data on that, from revenues to profits to return on capital.

As for the independent variables, some of these, such as R&D spending, are not tainted. Much trickier is what happens inside a company, such as quality of management, customer orientation, company culture, etc.

Rosenzweig explores the question of whether customer focus leads to better company performance. It probably does. However, in order to measure the effect of customer focus on performance objectively, we should not look at magazine and newspaper articles–since these are impacted by the Halo Effect. Nor should we ask company employees about their customer focus. How a company is performing–well or poorly–will impact the opinions of managers and employees regarding customer focus.

Similar logic applies to the question of how corporate culture impacts business performance. Surveys of managers and employees will be tainted by the Halo Effect. Yes, corporate culture impacts business performance. But to figure out the statistical correlation, we have to be sure to avoid data likely to be skewed by the Halo Effect.

Delusion Two: The Delusion of Correlation and Causality

Rosenzweig gives the example of employee turnover and company performance. If there is a statistical correlation between the two, then what does that mean? Does lower employee turnover lead to higher company performance? That sounds reasonable. On the other hand, does higher company performance lead to lower employee turnover? That could very well be the case.

Potential confusion about correlation versus causality is widespread when it comes to the study of business.

One way to get some insight into potential causality is to conduct alongitudinal study, looking at independent variables in one period and hypothetically dependent variables in some later period. Rosenzweig:

One recent study, by Benjamin Schneider and colleagues at the University of Maryland, used a longitudinal design to examine the question of employee satisfaction and company performance to try to find out which one causes which. They gathered data over several years so they could watch both changes in satisfaction and changes in company performance. Their conclusion? Financial performance, measured by return on assets and earnings per share, has a more powerful effect on employee satisfaction than the reverse. It seems that being on a winning team is a stronger cause of employee satisfaction; satisfied employees don’t have as much of an effect on company performance. How were Schneider and his colleagues able to break the logjam and answer the question of which leads to which? By gathering data over time.

Delusion Three: The Delusion of Single Explanations

Rosenzweig describes two studies that were carefully conducted, one on the effect of market orientation on company performance, and the other on the effect of CSR–corporate social responsibility–on company performance. The studies were careful in that they didn’t just ask for opinions. They asked about different activities in which the company did or did not engage.

The conclusion of the first study was that market orientation is responsible for 25 percent of company performance. The second study concluded that CSR is responsible for 40 percent of company performance. Rosenzweig asks: Does that mean that market orientation and CSR together explain 65 percent of company performance? Or do the variables overlap to an extent? The problem with studying a single cause of company performance is that you don’t know if part of the effect may be due to some other variable you’re not measuring. If a company is well-managed, then wouldn’t that be seen in market orientation and also in CSR?

(Photo byJ¶rg St¶ber)

We could throw human resource management–HRM–into the mix, too. Same goes for leadership. One study found that good leadership is responsible for 15 percent of company performance. But is that in addition to market orientation, CSR, and HRM? Or do these things overlap to an extent? It’s likely that there is significant overlap among these four variables.

One problem is that many researchers would like to tell a clear story about cause and effect. Admitting that many key variables likely overlap means that the story is much less clear. People–especially if busy or pressured–prefer simple stories where cause and effect seem obvious.

Furthermore, many important questions are at the intersection of different fields. Rosenzweig gives the example of decision making, which involves psychology, sociology, and economics. The trouble is that an expert in marketing will tend to exaggerate the importance of marketing. An expert in CSR will tend to exaggerate the importance of CSR. And so forth for other specialties.

SEARCHING FOR STARS, FINDING HALOS

Rosenzweig lists the eight practices of America’s best companies according toIn Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies, published by Tom Peters and Bob Waterman in 1982:

- A bias for action–a preference for doing something–anything–rather than sending a question through cycles and cycles of analyses and committee reports.

- Staying close to the customer–learning his preferences and catering to them.

- Autonomy and entrepreneurship–breaking the corporation into small companies and encouraging them to think independently and competitively.

- Productivity through people–creating in all employees the awareness that their best efforts are essential and that they will share in the rewards of the company’s success.

- Hands-on, value-driven–insisting that executives keep in touch with the firm’s essential business.

- Stick to the knitting–remaining with the business the company knows best.

- Simple form, lean staff–few administrative layers, few people at the upper levels.

- Simultaneous loose-tight properties–fostering a climate where there is dedication to the central values of the company combined with a tolerance for all employees who accept those values.

Rosenzweig points out that this list looks familiar: Care about your customers. Have strong values. Create a culture where people can thrive. Empower your employees. Stay focused.

If these look correlated, says Rosenzweig, that’s because they are. The best companies do all of them. Of course, again there’s the Halo Effect. If you isolate the top-performing companies (43 of them in this case), and then ask managers and employees about customer focus, values, culture, leadership, focus, etc., then you won’t know what caused what. Did clear strategy, good organization, strong corporate culture, and customer focus lead to the high performance? Or do people view high-performing companies as doing well in these areas?

(Image by Eriksvoboda)

When the book was published in 1982, there was a widespread concern among American businesses that Japanese companies were better overall. Peters and Waterman made the point that the leading American businesses were doing well in a variety of key areas. This message was viewed not only as inspirational, but even as patriotic. It was the right story for the times.

Many thought thatIn Search of Excellence contained scientific knowledge: if x, then y (with probability z).People thought that if they implemented the principles highlighted by Peters and Waterman, then they would be successful in business.

However, just two years later, some of the excellent companies did not seem as excellent as before. Some were blamed for changing–not sticking to their knitting. Others were blamed for NOT changing–not being adaptable enough, not taking action. More generally, some were blamed for overemphasizing certain principles, while underemphasizing other principles.

Rosenzweig examined the profitability of 35 of the 43 excellent companies–the 35 companies for which data were available because these companies were public. He found that, in the five years after 1982, 30 out of 35 had a decline in profitability. If these were truly excellent companies, then such a decline for 30 of 35 doesn’t make sense.

(Image by Dejan Lazarevic)

Rosenzweig observes that it’s possible that the previous success of these companies was due to more than the eight principles identified by Peters and Waterman. And so changes in other variables may explain the subsequent declines in profitability. It’s also possible–because Peters and Waterman identified 43 highly successful companies and then interviewed managers at those companies–that the Halo Effect came into play. The eight principles may reflect attributions that people tend to make about currently successful companies.

Delusion Four: The Delusion of Connecting the Winning Dots

You can’t choose a sample based only on the dependent variable you’re trying to test. The dependent variable in this case is successful companies. If all you look at is successful companies, then you won’t be able to compare successful companies directly to unsuccessful companies in order to learn about their respective causes–the independent variables. Rosenzweig refers to this error as theDelusion of Connecting the Winning Dots. You can connect the dots any way you wish, but following this approach, you can’t learn about the independent variables that lead to success.

Like many areas of social science, it’s not easy. You can’t run an experiment where you take 100 companies, and manage half of them one way, and half of them another way, and then compare results.

(Image by Macrovector)

Jim Collins and Jerry Porras isolated 18 companies based on excellent performance over a long period of time. Also, for each of these companies, Collins and Porras identified a similar company that had been less successful. This at least could avoid the error that Peters and Waterman made. As Collins and Porras said, if all you looked at were successful companies, you might find that they all reside in buildings.

Collins, Porras, and their team read more than 100 books and looked at more than 3,000 documents. All told, they had a huge amount of data. They certainly worked very hard. But that in itself does not increase the scientific validity of their study.

Collins and Porras claimed to have found “timeless principles,” which they listed:

- Having a strong core ideology that guides the company’s decisions and behavior

- Building a strong corporate culture

- Setting audacious goals that can inspire and stretch people–so-called big hairy audacious goals, or BHAGs

- Developing people and promoting them from within

- Creating a spirit of experimentation and risk taking

- Driving for excellence

Unfortunately, much of the data came from books, the business press, and company documents, all likely to contain Halos. They also conducted interviews with managers, who were asked to look back on their success and explain the reasons. These interviews were probably tinged by Halos in many cases. Some of the principles identified may have led to success. However, successful companies were also likely to be described in these terms. The Halo Effect hadn’t been dealt with by Collins and Porras.

Rosenzweig looked at profitability over the subsequent five years. Eleven companies saw profits decline. One was unchanged. Only five of the best companies had profits increase. It seems the “master blueprint for long-term prosperity” is largely a delusion, writes Rosenzweig.

(Graph by Experimental)

It’s not just some of the companies, but most of the companies that saw profits decline. Characterizations of the “best” companies were probably impacted significantly by the Halo Effect. The very fact that these companies had been doing well for some time led many to see them as having positive attributes across the board.

Delusion Five: The Delusion of Rigorous Research

As noted, psychologist Philip Tetlock tracked the predictions of 284 leading experts over two decades. Tetlock looked at over 27,000 predictions in real time of the form: more of x, no change in x, or less of x. He found that these predictions were no better than random chance.

Many experts have deep knowledge–historical or otherwise–that can give us valuable insights into human affairs. Some of this expertise is probably accurate. But until we have testable predictions, it’s difficult to say which hypotheses are true and to what degree.

We should never forget the difference between scientific knowledge and other types of knowledge, including stories. It’s very easy for us humans to be overconfident and deluded, especially if certain stories are the result of “many years of hard work.”

Delusion Six: The Delusion of Lasting Success

Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan looked at companies in the S&P 500 from 1957 to 1997. By 1997, only 74 out of the original largest 500 companies were still in the S&P 500. Of those 74 survivors, how many outperformed the S&P 500 over those 40 years? Only 12.

Foster and Kaplan conclude:

KcKinsey’s long-term studies of corporate birth, survival, and death in America clearly show that the corporate equivalent of El Dorado, the golden company that continually performs better than the markets,has never existed. It is a myth. Managing for survival, even among the best and most revered corporations, does not guarantee strong long-term performance for shareholders. In fact, just the opposite is true. In the long run, the markets always win.

It’s not that busines success is completely random. Of course not. But there is usually a large degree of luck involved. More fundamentally, capitalism is about competition through innovation, orcreative destruction, as the great Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called it. There is some inherent unpredictability–or luck–in this endless process.

Delusion Seven: The Delusion of Absolute Performance

Kmart improved noticeably from 1994 to 2002, but Wal-Mart and Target were ahead at the beginning of that period, and they improved even faster than Kmart. Thus, although it would seem Kmart was doing the right things in terms of absolute performance, Kmart was falling even further behind in terms of relative performance.

In 2005, GM was making much better cars than in the 1980s. But its market share kept slipping, from 35 percent in 1990 to 25 percent in 2005. GM’s competitors were improving faster.

Rosenzweig sums it up:

The greater the number of rivals, and the easier for competitors to enter the market, and the more rapidly technology changes, the more difficult it is to sustain success. That’s an uncomfortable truth, because it admits that some elements of business performance are outside of our control. It’s far more appealing to downplay the relative nature of performance or ignore it completely. Telling a company it can achieve high performance, regardless of what competitors do, makes for a more attractive story.

Delusion Eight: The Delusion of the Wrong End of the Stick

InGood to Great, Collins argues that a company can decide to become great and follow the blueprint in the book. Part of the recipe is to be like a Hedgehog–to have a narrow focus and pursue it with great discipline. The problem, again, is that the role of chance–or factors outside one’s control–is not considered. (The terms “Hedgehog” and “Fox” come from an essay by Isaiah Berlin. The Hedgehog knows one big thing, whereas the Fox knows many things.)

(Image by Marek Uliasz)

Statistically, it’s possible that, on the whole, more Hedgehogs than Foxes failed. You could still argue that the potential upside for becoming a great company is so large that it’s worth taking the risk of being like a Hedgehog. But Collins doesn’t mention risk, or chance, at all.

Of course, we’d all prefer a story where greatness is purely a matter of choice. But it’s rarely that simple and luck nearly always plays a pivotal role.

Delusion Nine: The Delusion of Organizational Physics

For many questions in business, we can’t run experiments. That said, with enough care, important statistical correlations can be discovered. Other things can be measured even more precisely.

But to think that the study of business is like the science of physics is a delusion, at least for now.

It’s reasonable to suppose that, with enough scientific knowledge in neuroscience, genetics, psychology, economics, artificial intelligence, and related areas, eventually human behavior may become largely predictable. But there’s a long way to go.

THE MOTHER OF ALL BUSINESS QUESTIONS,TAKE TWO

By nature, we prefer stories where business success is entirely a result of choosing to do the right things, while not reaching success must be due to a failure to do the right things. But stories like this neglect the role of chance. Rosenzweig writes:

…all the emphasis on steps and formulas may obscure a more simple truth. It may further the fiction that a specific set of steps will lead, predictably, to success. And if you never achieve greatness, well, the problem isn’t with our formula–which was, after all, the product of rigorous research, of extensive data exhaustively analyzed–but with you and your failure to follow the formula. But in fact, the truth may be considerably simpler than these formula suggest. They may divert our attention from a more powerful insight–that while we can do many things to improve our chances of success, at its core business performance contains a large measure of uncertainty. Business performance may actually be simpler than it is often made out to be, but may also be less certain and less amenable to engineering with predictable outcomes.

There is a simpler way to think about business performance–suggested by Michael Porter–without neglecting the role of chance. Strategy is doing certain things different from rivals.Execution is people working together to create products by implementing the strategy. This is a reasonable way to think about business performance as long as you also note the role of chance.

It’s usually hard to know how potential customers will behave. There are, of course, many examples where, contrary to expectations, a product was embraced or rejected. Moreover, even if you correctly understand customers, competitors may come up with a better product.

There’s also the issue of technological change, which can be a significant source of unpredictability in some industries.

(Illustration by T. L. Furrer)

Clayton Christensen has demonstrated–inThe Innovator’s Dilemma–that frequently companies fail because they keep doing theright things, giving customers what they want. Meanwhile, competitors develop a new technology that, at first, is not profitable–which is part of why the company “doing the right things” ignores it. But then, unpredictably, some of these new technologies end up being popular and also profitable.

One good question is: What should a company do when its core comes under pressure? Should it redouble its focus on the core, like a Hedgehog? Or should it be adaptable, like a Fox? There are no good answers at the moment, says Rosenzweig. There are too many variables. Chance–or uncertainty–plays a key role.

Rosenzweig continues:

In the meantime, we’re left with the brutal fact that strategic choice is hugely consequential for a company’s performance yet also inherently risky. We may look at successful companies and applaud them for what seem, in retrospect, to have been brilliant decisions, but we forget that at the time those decisions were made, they were controversial and risky. McDonald’s bet on franchising looks smart today, but in the 1950s it was a leap in the dark. Dell’s strategy of selling direct now seems brilliant but was attempted only after multiple failures with conventional channels. Or, recalling companies we discussed in earlier chapters, remember Cisco’s decision to assemble a full range of product offerings through acquisitions or ABB’s bet on leading rationalization of the European power industry through consolidation and cost cutting. The managers who took those choices appraised a wide variety of factors and decided to be different from their rivals. We remember all of these decisions because they turned out well, but success was not inevitable. As James March of Stanford and Zur Shapira of New York University explained, “Post hoc reconstruction permits history to be told in such a way that ‘chance,’ either in the sense of genuinely probabilistic phenomena or in the sense of unexplained variation, is minimized as an explanation.” But chance DOES play a role, and the difference between a brilliant visionary and a foolish gambler is usually inferred after the fact, an attribution based on outcomes. The fact is, strategic choices always involve risk. The task of strategic leadership is to gather appropriate information and evaluate it thoughtfully, then make choice that, while risky, provide the best chances for success in a competitive industry setting.

(Image by Donfiore)

As for execution, certain practices do correlate with modestly higher performance. If leaders can identify the few areas where better execution is needed, then some progress can be made.

But inherent unpredictability is hidden by the Halo Effect. If a company succeeds, it’s easy to say it executed well. If a company fails, it’s natural to conclude that execution was poor. Often to a large extent, these conclusions are driven by the Halo Effect, even if there is some truth to them.

In brief, smart strategic choices and good execution–plus good luck–may lead to success, at least temporarily. But success brings challengers, some of whom will take greater risks that may work. There’s no formula to guarantee success. And if success is achieved, there’s no way to guarantee continued success over time.

MANAGING WITHOUT COCONUT HEADSETS

Given that there’s no simple formula that brings business success, what should we do? Rosenzweig answers:

A first step is to set aside the delusions that color so much of our thinking about business performance. To recognize that stories of inspiration may give us comfort but have little more predictive power than a pair of coconut headsets on a tropical island. Instead, managers would do better to understand that business success is relative, not absolute, and that competitive advantage demands calculated risks. To accept that few companies achieve lasting success, and that those that do are perhaps best understood as having strung together several short-term successes rather than having consciously pursued enduring greatness. To admit that, as Tom Lester of theFinancial Times so neatly put it, “the margin between success and failure is often very narrow, and never quite as distinct or as enduring as it appears at a distance.” By extension, to recognize that good decisions don’t always lead to favorable outcomes, that unfavorable outcomes are not always the result of mistakes, and therefore to resist the natural tendency to make attributions based solely on outcomes. And finally, to acknowledge that luck often plays a role in company success. Successful companies aren’t “just lucky”–high performance isnot purely random–but good fortune does play a role, and sometimes a pivotal one.

Rosenzweig mentions Robert Rubin as a good example of someone who learned to make decisions in terms of scenarios and their probabilities.

(Image by Elnur)

Rubin worked for eight years in the Clinton administration, first as director of the White House National Economic Council and later as secretary of the Treasury. Prior to working in the Clinton administration, Rubin toiled for twenty-six years at Goldman Sachs.

Rubin first learned about the fundamental uncertainties of the world when he studied philosophy as an undergraduate. He learned to view every proposition with skepticism. Later at Goldman Sachs, Rubin saw first-hand that one had to consider possible outcomes and their associated probabilities.

Rubin spent years in risk arbitrage. Many times Goldman made money, but roughly one out of every seven times, Goldman lost money. Sometimes the loss would greatly exceed Goldman’s worst-case scenario. But occasionally large and painful losses didn’t mean that Goldman’s decision-making process was flawed. In fact, if Goldman wasn’t taking some losses, then they almost certainly weren’t taking enough risk.

(Photo by Alain Lacroix)

Rosenzweig asks: If a large and painful loss doesn’t mean a mistake, then what does?

We have to take a close look at the decision process itself, setting aside the eventual outcome. Had the right information been gathered, or had some important data been overlooked? Were the assumptions reasonable, or had they been flawed? Were calculations accurate, or had there been errors? Had the full set of eventualities been identified and their impact estimated? Had Goldman Sachs’s overall risk portfolio been properly considered?

Once again, a profitable outcome doesn’t necessarily mean the decision was good. An unprofitable outcome doesn’t necessarily mean the decision was bad. If you’re making decisions under uncertainty–probabilistic decisions–the only way to improve is to evaluate the process of decision-making independently of specific outcomes.

Of course, often important decisions for an individual business are quite infrequent. Rosenzweig highlights important lessons for managers:

- If independent variables aren’t measured independently, we may find ourselves standing hip-deep in Halos.

- If the data are full of Halos, it doesn’t matter how much we’ve gathered or how sophisticated our analysis appears to be.

- Success rarely lasts as long as we’d like–for the most part, long-term success is a delusion based on selection after the fact.

- Company performance is relative, not absolute. A company can get better and fall further behind at the same time.

- It may be true that many successful companies bet on long shots, but betting on long shots does not often lead to success.

- Anyone who claims to have foundlaws of business physics either understands little about business, or little about physics, or both.

- Searching for the secrets of business success reveals little about the world of business but speaks volumes about the searchers–their aspirations and their desires for certainty.

Getting rid of delusions is a crucial step. Furthermore, writes Rosenzweig, a wise manager knows:

- Any good strategy involves risk. If you think your strategy is foolproof, the fool may well be you.

- Execution, too, is uncertain–what works in one company with one workforce may have different results elsewhere.

- Chance often plays a greater role than we think, or than successful managers usually like to admit.

- The link between inputs and outcomes is tenuous. Bad outcomes don’t always mean that managers made mistakes; and good outcomes don’t always mean they acted brilliantly.

- But when the die is cast, the best managers act as if chance is irrelevant–persistence and tenacity are everything.

Of course, none of this guarantees success. But the sensible goal is to improve your chances of success.

BOOLE MICROCAP FUND

An equal weighted group of micro caps generally far outperforms an equal weighted (or cap-weighted) group of larger stocks over time. See the historical chart here: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

This outperformance increases significantly by focusing on cheap micro caps. Performance can be further boosted by isolating cheap microcap companies that show improving fundamentals. We rank microcap stocks based on these and similar criteria.

There are roughly 10-20 positions in the portfolio. The size of each position is determined by its rank. Typically the largest position is 15-20% (at cost), while the average position is 8-10% (at cost). Positions are held for 3 to 5 years unless a stock approachesintrinsic value sooner or an error has been discovered.

The mission of the Boole Fund is to outperform the S&P 500 Index by at least 5% per year (net of fees) over 5-year periods. We also aim to outpace the Russell Microcap Index by at least 2% per year (net). The Boole Fund has low fees.

If you are interested in finding out more, please e-mail me or leave a comment.

My e-mail: jb@boolefund.com

Disclosures: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed.No part of this article may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of Boole Capital, LLC.

Как сделать ноги красивыми в домашних условиях? Знакомый вопрос? Увы, но года берут свое. Если раньше хорошенькие от природы ножки не нуждались в особом уходе, то с возрастом ситуация меняется. Ограничение активности, неправильное питание, появление жирка не лучшим образом сказываются на состоянии ног. Но не все потеряно! Немного свободного времени и желание смогут исправить ситуацию!

[url=https://chel-week.ru/33533-sdelat-nogi-krasivymi-i-stroynymi.html]как сделать форму ног красивой[/url]

[url=https://chel-week.ru/33533-sdelat-nogi-krasivymi-i-stroynymi.html][img]https://ezdejo.hu/upload/313/perillisz-honalj-es-bikini.jpg[/img][/url]

world pharmacy store viagra sex pills viagra super viagra review

super slots казино официальный сайт

[url=https://superslot-casino.ru/]казино супер слот[/url]

Make thousands of bucks. Financial robot will help you to do it!

Link – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

сол казино скачать

[url=https://sol-casino.host/mobile]скачать сол казино на андроид[/url]

казино плей фортуна зеркало

[url=https://playfortuna-casino.host/games]игровые автоматы плей фортуна играть бесплатно[/url]

вулкан slots регистрация

[url=https://vulkan-slots.site/contact]вулкан слотс телефон[/url]

New project started to be available today, check it out

http://yumypornstar.fetlifeblog.com/?bridget

redtube married porn access to porn on the internet gisele girls do porn rapidshare uncensored teens porn names of top porns

My new hot project|enjoy new website

http://shemaleapp.ashemaleporn.allproblog.com/?anya

demia moore porn complete abuse and humiliation porn solange porn funny porn bluppers asian big clit porn

Wow! This Robot is a great start for an online career.

Link – – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

http://whatsapplanding.is-great.net/ – бот в ватсап

http://gengaz.ru

[url=http://www.alkraft.ru/production/metallicheskaya-dverca-nazhimnaya]ревизионные люки[/url] или [url=http://www.alkraft.ru/protivopozharnye-lyuki]скрытые люки под плитку[/url]

http://www.alkraft.ru/production/metallicheskaya-dverca-nazhimnaya

[url=http://medspravka24-krasnoyarsk.ru]купить медицинскую справку 001-гс у[/url] – подробнее на нашем сайте [url=http://medspravka24-krasnoyarsk.ru]medspravka24-krasnoyarsk.ru[/url]

Личная [url=http://medspravka24-krasnoyarsk.ru]медицинская книжка[/url] ([url=http://medspravka24-krasnoyarsk.ru]санитарная книжка[/url]) – официальный документ строгой отчетности. В санитарной книжке отражаются все данные о результатах периодических осмотров, сдачи анализов и прививках, наличия инфекционных заболеваний, а также о прохождении курсов по гигиеническому воспитанию и аттестации.

# 1 financial expert in the net! Check out the new Robot.

Link – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

Nude Sex Pics, Sexy Naked Women, Hot Girls Porn

http://pornastrid.relayblog.com/?noelia

y o porn free teen girls basketball shorts porn bridgette monroe free porn sleep assualt porn free teens and older guy porn

Revolutional update of captchas regignizing software “XEvil 5.0”:

Captchas regignizing of Google (ReCaptcha-2 and ReCaptcha-3), Facebook, BitFinex, Bing, Hotmail, SolveMedia, Yandex,

and more than 12000 another size-types of captchas,

with highest precision (80..100%) and highest speed (100 img per second).

You can use XEvil 5.0 with any most popular SEO/SMM programms: iMacros, XRumer, SERP Parser, GSA SER, RankerX, ZennoPoster, Scrapebox, Senuke, FaucetCollector and more than 100 of other programms.

Interested? You can find a lot of demo videos about XEvil in YouTube.

FREE DEMO AVAILABLE!

See you later 😉

завидный веб сайт

[url=https://sexreliz.net/anal/488-ottrahal-v-popku-bolshim-chlenom.html]https://sexreliz.net/anal/488-ottrahal-v-popku-bolshim-chlenom.html[/url]

visit this site [url=https://empirestuff.org/]empire market dark[/url]

Financial robot guarantees everyone stability and income.

Link – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

игровые автоматы казино х официальный

[url=https://online-kazino-x.space/zerkalo]casino x сегодня[/url]

Read More Here https://hydramirror2020.com

Bright Starts Fun with Sesame Street Friends Activity Gym and Playmat, Ages 0-12 months

[url=https://pegasbaby.com/minichamps-bmw-3-5-csl-le-mans-1976-1-18-72069]MINICHAMPS – BMW 3.5 CSL – Le Mans 1976 – 1/18[/url]

отменный вебсайт

[url=https://erotag.com/]Интимные фото голых баб в постели[/url]

хоть куда веб сайт

[url=https://pizdeishn.net/devstven/140-dacha.html]https://pizdeishn.net/devstven/140-dacha.html[/url]

Learn how to make hundreds of backs each day.

Link – – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

The huge income without investments is available.

Link – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

Pampers Aqua Pure Natural Sensitive Baby Wipes, 8X Pop-Top, 448 Count

[url=https://pegasbaby.com/prolriy-baby-kids-intelligence-development-cloth-3d-animal-tail-book-educational-toy-71949]Prolriy Baby Kids Intelligence Development Cloth 3D Animal Tail Book Educational Toy[/url]

The online job can bring you a fantastic profit.

Link – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

Фиброцемент Фиброцементный агломерат – искусственное сырье, которое производят в результате смешивания и обработки песка, цемента, воды и других добавок.

Полученный материал обладает высокой прочностью, способностью выдерживать механические нагрузки, небольшим весом, невысокой ценой.

Одной из областей применения листовых изделий из фиброцементных смесей является наружная отделка стен домов.

В навесных фасадных системах используют [url=https://stroy.msk.su/oblicovka-dlia-facada/4-fibrocement.html]фиброцементные панели цена[/url] для получения финишного слоя.

Перед облицовкой фасада к стенам монтируют обрешетку из стоек и ригелей.

Между экраном и стеной образуется воздушная прослойка, которая необходима для свободной циркуляции воздушных потоков.

НФС из фасадных фиброцементных панелей популярны из-за эффектного вида, быстрой и простой установки, широкому выбору расцветок, текстур.

#Hookahmagic

Мы всегда с Вами и стараемся нести только позитив и радость.

Ищите Нас в соцсетях,подписывайтесь и будьте в курсе последних топовых событий.

Строго 18+

Кальянный бренд Фараон давно завоевал сердца ценителей кальянной культуры вариативностью моделей кальянов,

приемлемым качеством и низкой ценовой политикой. Именно эти факторы играют главную роль в истории его успеха. Не упускайте очевидную выгоду и вы! Заказывайте кальян Pharaon (Фараон) 2014 Сlick в интернет-магазине HookahMagic и оформляйте доставку в любой регион РФ. Мы гарантируем быструю доставку и высокое качество предоставляемой продукции.

https://h-magic.su/chosen

Удачных вам покупок!

Hello! [url=http://lolasix.info/]walmart pharmacy lasix[/url] where to buy lasix without prescription

Start making thousands of dollars every week.

Link – https://tinyurl.com/y7t5j7yc

Зеркало сайта Гидра, как им пользоваться?

Не всегда получается открыть официальный сайт маркетплейса Hydra2web. В некоторых случаях он может быть заблокирован провайдером. В этом случае, вам нужно использовать [url=https://hydraruzixpnew4afonion.com/]Гидра зеркало[/url], чтобы попасть на сайт и делать покупки в обычном режиме. Зеркало сайта находится на другом хостинге и может иметь другое доменное имя. Список доступных ресурсов всегда можно найти на официальном сайте или тематических сообществах.

Как оплатить товары на сайте Hydra market

Подобные ресурсы, включая Hydraruzxpnew4af, принимают исключительно криптовалюту. Это необходимо для того, чтобы иметь максимальную степень анонимности. Ведь крипто кошелек почти невозможно отследить.

кэшбэк в казино вавада

[url=https://vavada-casino-online.fun/]вавада казино официальный сайт вход[/url]

казино франк 100 бесплатных вращений регистрация

[url=https://frank-casino-official.xyz/games]jackpot frank casino[/url]

адмирал х обзор

[url=https://admiral-x-official.fun/mobile]адмирал х 1000 рублей за регистрацию мобильная[/url]

Hi there! [url=http://loprozac.info/]20 mg paxil[/url] 10 mg paxil for anxiety paxil online pharmacy

quick loans easy payday loans personal loans with poor credit

Годнота спасибо

Store cloned cards [url=http://buyclonedcard.com]http://buyclonedcard.com[/url]

We are an anonymous ensemble of hackers whose members mad in on the be full of every country. Our reception is connected with skimming and hacking bank accounts. We one’s hands on been successfully doing this since 2015. We proffer you our services into the levy of cloned bank cards with a worthy balance. Cards are produced all about our specialized paraphernalia, they are politely untainted and do not fa‡ade any danger.

Buy Credit Cards http://buyclonedcard.comм

Препараты качественные,купили на сайте anticancer24.ru

Доставили из Москвы за 3 дня

софосбувир +и даклатасвир лечение форум

Even a child knows how to make $100 today with the help of this robot.

Link – https://plbtc.page.link/zXbp

Pampers Cruisers Active Fit Taped Diapers, Size 3, 140 ct

[url=https://pegasbaby.com/valentine-14-super-cute-turtle-money-bank-69484]Valentine 14″ Super-Cute Turtle Money Bank[/url]

франк казино промокод

[url=https://frank-casino-official.xyz/bonus]коды франк казино[/url]

казино x обзор

[url=https://online-kazino-x.space/bonusy]казино х бездепозитный бонус[/url]

play fortuna casino СЂРѕСЃСЃРёСЏ

[url=https://playfortuna-casino.host/mirror]плей фортуна казино официальный сайт рабочее зеркало[/url]

vavada фриспины за регистрацию

[url=https://vavada-casino-online.fun/]официальный сайт vavada[/url]

sol casino зеркало

[url=https://sol-casino.host/bonus]казино сол бонусный код[/url]

Препараты качественные,купили на сайте anticancer24.ru

Доставили из Москвы за 3 дня

софосбувир +и даклатасвир дженерики

Препараты качественные,купили на сайте anticancer24.ru

Доставили из Москвы за 3 дня

можно ли софосбувир +и даклатасвир

Store cloned cards [url=http://buyclonedcard.com]http://buyclonedcard.com[/url]

We are an anonymous alliance of hackers whose members the sphere in not quite every country. Our attainment is connected with skimming and hacking bank accounts. We come into the possession of been successfully doing this since 2015. We proffer you our services during the precisely the buying of cloned bank cards with a gargantuan balance. Cards are produced on of our specialized instruments, they are categorically uncomplicated and do not place any danger.

Buy Credit Cards http://buyclonedcard.comм

insta

hookah.magic_su

insta

отличные цены

Лучшие в городе

Доставка в любую точку мира!!!

hookah.magic_su