The Innovator’s Dilemma is a business classic by Clayten M. Christensen. Good companies frequently fail precisely because they are good. Good companies invest insustaining technologies,which are generally high-functioning, high-margin, and demanded by customers, instead ofdisrupting technologies,which start out relatively low-functioning, low-margin, and not demanded by customers.

The Innovator’s Solution, by Clayton Christensen and Michael Raynor, aims at presenting solutions to the innovator’s dilemma.

(Illustration by Rapeepon Boonsongsuwan)

Outline:

- The Growth Imperative

- How Can We Beat Our Most Powerful Competitors?

- What Products Will Customers Want to Buy?

- Who Are the Best Customers For Our Products?

- Getting the Scope of the Business Right

- How to Avoid Commoditization

- Is Your Organization Capable of Disruptive Growth?

- Managing the Strategy Development Process

- There is Good Money and There is Bad Money

- The Role of Senior Executives in Leading New Growth

THE GROWTH IMPERATIVE

As companies grow larger, it becomes more difficult to grow. But shareholders demand growth. Many companies invest aggressively to try to create growth, but most fail to do so. Why is creating growth so hard for larger companies?

(Image by Bearsky23)

Christensen and Raynor note three explanations that seem plausible but are wrong:

- Smarter managers could have succeeded. But when it comes to sustaining growth that creates shareholder value, 90 percent of all publicly traded companies have failed to create it for more than a few years. Are 90 percent of all managers are below average?

- Managers become risk-averse. But here again, the facts don’t support the explanation. Managers frequently bet billion-dollar companies on one innovation.

- Creating new-growth businesses is inherently unpredictable. The odds of success are low, as reflected by how venture capitalists invest. But there’s far more to the process of creating growth than just luck.

The innovator’s dilemma causes good companies to invest in high-functioning, high-margin products that their current customers want. This can be seen in the process companies follow to fund ideas:

The process of sorting through and packaging ideas into plans that can win funding… shapes those ideas to resemble the ideas that were approved and became successful in the past. The processes have in fact evolved to weed out business proposals that target markets where demand might be small. The problem for growth-seeking managers, of course, is that the exciting growth markets of tomorrow are small today.

…

A dearth of good ideas is rarely the core problem in a company that struggles to launch exciting new-growth businesses. The problem is in the shaping process. Potentially innovative new ideas seem inexorably to be recast into attempts to make existing customers still happier.

It’s possible to gain greater understanding of how companies create profitable growth. If we can develop a better theory, then we can make better predictions. There are three stages in theory-building, say Christensen and Raynor:

- Describe the phenomena in question.

- Classify the phenomena into categories.

- Explain what causes the phenomena, and under what circumstances.

Building a theory is iterative. Scientists keep improving their descriptions, classifications, and causal explanations.

Frequently there is not enough understanding of the circumstances under which businesses succeed.

To know for certain what circumstances they are in, managers also must know what circumstances they arenot in. When collectively exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories of circumstances are defined, things get predictable: We can state what will cause what and why, and can predict how that statement of causality might vary by circumstance.

HOW CAN WE BEAT OUR MOST POWERFUL COMPETITORS?

(Illustration by T. L. Furrer)

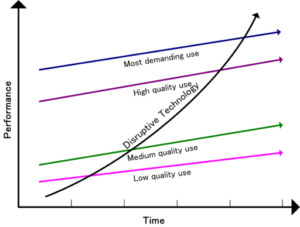

Compared to existing products, disruptive innovations start out simpler, more convenient, and less expensive.

Once the disruptive product gains a foothold in new or low-end markets, the improvement cycle begins. And because the pace of technological progress outstrips customers’ ability to use it, the previously not-good-enough technology eventually improves enough to intersect with the needs of more demanding customers. When that happens, the disruptors are on a path that will ultimately crush the incumbents.

Most disruptive innovations are launched by entrants. A good example is minimills disrupting integrated steel companies.

Minimills discovered that by melting scrap metal, they could make steel at 20 percent lower cost than the integrated steel mills. But the quality of steel the minimills initially produced was low due to the use of scrap metal. Their steel could only be used for concrete reinforcing bar (rebar).

The rebar market was naturally more profitable for the minimills, due to their lower cost structure. The integrated steel mills were happy to give up what for them was a lower-margin business. The minimills were profitable as long as they were competing against integrated steel mills that were still supplying the rebar market. Once there were no integrated steel mills left, the price of the rebar dropped 20 percent to reflect the lower cost structure of minimills.

This pattern kept repeating. The minimills looked up-market again. The minimills expanded their capacity to make angle iron, and thicker bars and rods. The minimills reaped significant profits as long as they were competing against integrated steel mills still left in the market for bar and rod. Meanwhile, integrated steel mills gradually abandoned this market because it was lower-margin for them. After the last integrated steel mill dropped out, the price of bar and rod dropped 20 percent to reflect the costs of minimills.

So the mimimills looked up-market again to structural beams. Most experts thought minimills wouldn’t be able to roll structural beams. But the minimills were highly motivated and came up with very clever innovations. Once again, the minimills experienced nice profits as long as they were competing against integrated steels mills. But when the last integrated steel mill dropped out of the structural beam market, the price dropped 20 percent.

(Image by Megapixie, via Wikimedia Commons)

Christensen and Raynor add:

The sequence repeated itself when the leading minimill, Nucor, attacked the steel sheet business. Its market capitalization now dwarfs that of the largest integrated steel company, U.S. Steel. Bethlehem Steel is bankrupt as of the time of this writing.

This is not a history of bungled steel company management. It is a story of rational managers facing the innovator’s dilemma: Should we invest to protect the least profitable end of our business, so that we can retain our least loyal, most price-sensitive customers? Or should we invest to strengthen our position in the most profitable tiers of our business, with customers who reward us with premium prices for better products?

The authors note that these patterns hold for all companies, not just technology companies. Also, they define “technology” as “the process that any company uses to convert inputs of labor, materials, capital, energy, and information into outputs of greater value.” Christensen and Raynor:

Disruption does not guarantee success, but it sure helps: The Innovator’s Dilemma showed that following a strategy of disruption increased the odds of creating a successful growth business from 6 percent to 37 percent.

New-market disruptions relate to consumers who previously lacked the money or skills to buy and use the product, or they relate to different situations in which the product can be used. New-market disruptions compete with”nonconsumption.”

Low-end disruptions attack the least profitable and most overserved customers in the original market.

Examples of new-market disruptions:

The personal computer and Sony’s first battery-powered transistor pocket radio were new-market disruptions, in that their initial customers were new consumers – they had not owned or used the prior generation of products and services. Canon’s desktop photocopiers were also a new-market disruption, in that they enabled people to begin conveniently making their own photocopies around the corner from their offices, rather than taking their originals to the corporate high-speed photocopy center where a technician had to run the job for them.

The authors then explain low-end disruptions:

…Disruptions such as steel minimills, discount retailing, and the Korean automakers’ entry into the North American market have been pure low-end disruptions in that they did not create new markets– they were simply low-cost business models that grew by picking off the least attractive of the established firms’ customers.

Many disruptions are a hybrid of new-market and low-end.

Christensen and Raynor suggest three sets of questions to determine if an idea has disruptive potential. The first set of questions relates to new-market potential:

- Is there a large population of people who historically have not had the money, equipment, or skill to do this thing for themselves, and as a result have gone without it altogether or have needed to pay someone with more expertise to do it for them?

- To use the product or service, do customers need to go to an inconvenient, centralized location?

The second set of questions concerns low-end disruptions:

- Are there customers at the low-end of the market who would be happy to purchase a product with less (but good enough) performance if they could get it at a lower price?

- Can we create a business model that enables us to earn attractive profits at the discount prices required to win the business of these overserved customers at the low end?

A final question is a litmus test:

- Is the innovation disruptive to all of the significant incumbent firms in the industry? If it appears to be sustaining to one or more significant players in the industry, then the odds will be stacked in that firm’s favor, and the entrant is unlikely to win.

WHAT PRODUCTS WILL CUSTOMERS WANT TO BUY?

Christensen and Raynor:

All companies face the continual challenge of defining and developing products that customers will scramble to buy. But despite the best efforts of remarkably talented people, most attempts to create successful new products fail. Over 60 percent of all new-product development efforts are scuttled before they ever reach the market. Of the 40 percent that do see the light of day, 40 percent fail to become profitable and are withdrawn from the market.

(Photo by Kirill Ivanov)

The authors stress that customers “hire” products to do “jobs.” We need to think about what customers are trying to do and the circumstances involved.

…This is how customers experience life. Their thought processes originate with an awareness of needing to get something done, and then they set out to hire something or someone to do the job as effectively, conveniently, and inexpensively possible… In other words, the jobs that customers are trying to get done or the outcomes that they are trying to achieve constitute a circumstance-based categorization of markets.

The authors give the example of milkshakes. What are the jobs that people “hire” milkshakes for? Nearly half of all milkshakes are bought early the morning. Often these customers want to have a less boring commute. Also, a morning milkshake helps to avoid feeling hungry at 10:00. At other times of day, parents were observed buying milkshakes for their children as a way to calm them down. Armed with this knowledge, milkshake sellers can improve the milkshakes they sell at specific times of day.

The key here is observing what people are trying to accomplish. Develop and test hypotheses accordingly. Then develop products rapidly and get fast feedback.

It’s often much easier to figure out how to develop a low-end disruption. That’s because the market already exists. The goal is to move gradually up-market.

Why do many executives, instead of following jobs-to-be-done segmentation, focus on market segments not aligned with how customers live their lives? Christensen and Raynor say there are at least four reasons:

- Fear of focus.

- Senior executives’ demand for quantification of opportunities.

- The structure of channels.

- Advertising economics and brand strategies.

The first two reasons relate to resource allocation. The second two reasons concern the targeting of customers rather than circumstances.

Focus is scary – until you realize that it only means turning your back on markets you could never have anyway. Sharp focus on jobs that customers are trying to get done holds the promise ofgreatly improving the odds of success in new-product development.

(Photo by Creativefire)

Rather than understand how customers and markets work, most market research is focused on defining the size of the opportunity. This is the mistake of basing research on the available data instead of finding out about the jobs customers are trying to do.

When they frame the customer’s world in terms of products, innovators start racing against competitors by proliferating features, functions, and flavors of products that mean little to customers. Framing markets in terms of customer demographics, they average across several different jobs that arise in customers’ lives and develop one-size-fits-all products that rarely leave most customers fully satisfied. And framing markets in terms of an organization’s boundaries further restricts innovators’ abilities to develop products that will truly help their customers get the job done perfectly.

Regarding the structure of channels:

Many retail and distribution channels are organized by product categories rather than according to the jobs that customers need to get done. This channel structure limits innovators’ flexibility in focusing their products on jobs that need to be done, because products need to be slotted into the product categories to which shelf space has been allocated.

Christensen and Raynor give the example of a manufacturer of power tools. It learned that when workers were hanging a door, they used seven different tools, none of which was specific to the task. The manufacturer invented a new tool that noticeably simplified the job. But retail chains refused to sell the new tool because they didn’t have pre-existing shelf space for it.

Brands should be based on jobs to be done.

If a brand’s meaning is positioned on a job to be done, then when the job arises in a customer’s life, he or she will remember the brand and hire the product. Customers pay significant premiums for brands that do a job well.

Some executives worry that a low-end disruption might harm their established brand. But they can avoid this issue by properly naming each product.

WHO ARE THE BEST CUSTOMERS FOR OUR PRODUCTS?

As long as a business can profit using discount prices, the business can do well selling a low-end innovation. It’s much harder to find new-market customers. How do you determine if nonconsumers will become consumers of a given product? Once again, the job-to-be-done perspective is crucial.

(Illustration by Alexmillos)

The authors continue:

A new-market disruption is an innovation that enables a larger population of people who previously lacked the money or skill now to begin buying and using a product and doing the job for themselves. From this point forward, we will use the termsnonconsumers andnonconsumption to refer to this type of situation, where the job needs to get done but a good solution historically has been beyond reach.

Christensen and Raynor identify four elements in new-market disruption:

- The target customers are trying to get a job done, but because they lack the money or skill, a simple, inexpensive solution has been beyond reach.

- These customers will compare the disruptive product to having nothing at all. As a result, they are delighted to buy it even though it may not be as good as other products available at high prices to current users with deeper expertise in the original value network. The performance hurdle required to delight such new-market customers is quite modest.

- The technology that enables the disruption might be quite sophisticated, but disruptors deploy it to make the purchase and use of the product simple, convenient, and foolproof. It is the “foolproofedness” that creates new growth by enabling people with less money and training to begin consuming.

- The disruptive innovation creates a whole new value network. The new consumers typically purchase the product through new channels and use the product in new venues.

When disruptions come, established firms must take two key steps: First, when it comes to resource allocation, identify the disruption as a threat. Second, those charged with building a new technology as a response should view their task as an opportunity. This group should be an independent entity within the overall company.

Disruptive channels are often required to reach new-market customers:

…A company’s channel includes not just wholesale distributors and retail stores, but any entity that adds value to or creates value around the company’s product as it wends its way toward the hands of the end user…

We use this broader definition of channel because there needs to be symmetry of motivation across the entire chain of entities that add value to the product on its way to the end user. If your product does not help all of these entities do their fundamental job better – which is to move up-market along their own sustaining trajectory toward higher-margin business – then you will struggle to succeed. If your product provides the fuel that entities in the channel need to move toward improved margins, however, then the energy of the channel will help your new venture succeed.

GETTING THE SCOPE OF THE BUSINESS RIGHT

It’s often advised to stick to your core competence. The trouble is that something that doesn’t seem core today may turn out to be critical tomorrow.

Consider, for example, IBM’s decision to outsource the microprocessor for its PC business to Intel, and its operating system to Microsoft. IBM made these decisions in the early 1980s in order to focus on what it did best – designing, assembling, and marketing computer systems… And yet in the process of outsourcing what it did not perceive to be core to the new business, IBM put into business the two companies that subsequently captured most of the profit in the industry.

The solution starts again with the jobs-to-be-done approach. If the current products are not good enough, integration is best. If the current products are more than good enough, outsourcing makes sense.

(Photo by Marek Uliasz)

Christensen and Raynor explain product architecture and interfaces:

An architecture is interdependent at an interface if one part cannot be created independently of the other part– if the way one is designed and made depends on the way the other is being designed and made. When there is an interface across which there are unpredictable interdependencies, then the same organization must simultaneously develop both of the components if it hopes to develop either component.

Interdependent architectures optimize performance, in terms of functionality and reliability. By definition, these architectures are proprietary because each company will develop its own interdependent design to optimize performance in a different way…

In contrast, a modular interface is a clean one, in which there are no unpredictable interdependencies across components or stages of the value chain. Modular components fit and work together in well-understood and highly defined ways. A modular architecture specifies the fit and function of all elements so completely that it doesn’t matter who makes the components or subsystems, as long as they meet the specifications…

Modular architectures optimize flexibility, but because they require tight specification, they give engineers fewer degrees of freedom in design. As a result, modular flexibility comes at the sacrifice of performance.

The authors point out that most products fall between the two extremes of interdependence and pure modularity.

When product functionality and reliability are not yet good enough, firms that build their products around proprietary, interdependent architectures have a competitive advantage. That’s because competitors with product architectures that are modular have less freedom and so cannot optimize performance.

The authors mention RCA, Xerox, AT&T, Standard Oil, and U.S. Steel:

These firms enjoyed near-monopoly power. Their market dominance was the result of the not-good-enough circumstance, which mandated interdependent product or value chain architectures and vertical integration. But their hegemony proved only temporary, because ultimately, companies that have excelled in the race to make the best possible products find themselves making products that are too good.

Eventually customers evolve in what they want. They become willing to pay for speed, convenience, and customization. Product architecture evolves towards more modular design. This deeply impacts industry structure. Independent, nonintegrated organizations become able to sell components and subsystems. Industry standards develop that specify modular interfaces.

HOW TO AVOID COMMODITIZATION

Many think commoditization is inevitable, no matter how good the innovation. Christensen and Raynor reached a different conclusion:

One of the most exciting insights from our research about commoditization is that whenever it is at work somewhere in a value chain, a reciprocal process of de-commoditization is at work somewhere else in the value chain. And whereas commoditization destroys a company’s ability to capture profits by undermining differentiability, de-commoditization affords opportunities to create and capture potentially enormous wealth.

Companies that position themselves at a place in the value chain where performance is not yet good enough will earn the profits when a disruption is occurring. Just as Wayne Gretsky sought to skate to where the puck would be (not where it is), companies should position themselves where the money will be (not where it is).

(Photo of Wayne Gretzky by Rick Dikeman, via Wikimedia Commons)

When products are not yet good enough, companies with interdependent, proprietary architecture have strong advantages in differentiation and in cost structures.

This is why, for example, IBM, as the most integrated competitor in the mainframe computer industry, held a 70 percent market share but made 95 percent of the industry’s profits: It had proprietary products, strong cost advantages, and high entry barriers… Making highly differentiable products with strong cost advantages is a license to print money, and lots of it.

Of course, as a company seeks to outdo competitors, eventually it overshoots on the reliability and functionality that customers can use. This leads to a change in the basis of competition. There’s evolution towards modular architectures. This process starts at the bottom of the market, where functionality overshoots first, and then moves gradually up-market.

Christensen and Raynor comment that “industry” itself is usually a faulty categorization. Value chains evolve as the processes of commoditization and de-commoditization gradually repeat over time.

What’s fascinating– it’s the innovator’s dilemma– is that as innovators are moving up the value chain, established firms gradually abandon their lower-margin products and focus on their higher-margin products. Established firms repeatedly focus on areas that increase their ROIC (return on invested capital) in the short term. But these same decisions move established firms away from where the profits will be in the future.

Brands are most valuable when products aren’t yet good enough. A brand can signal to potential customers that the products they seek will meet their standards. When the performance of the products becomes more than good enough, the power of brands diminishes. Christensen and Raynor:

The migration of branding power in a market that is composed of multiple tiers is a process, not an event. Accordingly, the brands of companies with proprietary products typically create value mapping upward from their position on the improvement trajectory– toward those customers who still are not satisfied with the functionality and reliability of the best that is available. But mapping downward from the same point– toward the world of modular products where speed, convenience, and responsiveness drive competitive success– the power to create powerful brands migrates away from the end-use product, toward the subsystems and the channel.

This has happened in heavy trucks. There was a time when the valuable brand, Mack, was on the truck itself. Truckers paid a significant premium for Mack the bulldog on the hood. Mack achieved its preeminent reliability through its interdependent architecture and extensive vertical integration. As the architectures of large trucks have become more modular, however, purchasers have come to care far more whether there is a Cummins or Caterpillar engine inside than whether the truck is assembled by Paccar, Navistar, or Freightliner.

IS YOUR ORGANIZATION CAPABLE OF DISRUPTIVE GROWTH?

Many innovations fail because the managers or corporations lack the capabilities to create a successful disruption. Often the very skills that cause a leading company to succeed – through sustaining innovations – cause the same company to fail when it comes to disruptive growth.

The authors define capability by what they call the RPV framework– resources, processes, and values.

Resources are usually people, or things such as technology and cash. What most often causes failure in disruptive growth is the wrong choice of managers. It’s often thought that right-stuff attributes, plus a string of uninterrupted successes, is the best way to choose leaders of a disruptive venture.

But the skills needed to run an established firm are quite different from the skills needed to manage a disruptive venture.

In order to be confident that managers have developed the skills required to succeed at a new assignment, one should examine the sorts of problems they have wrestled with in the past. It is not as important that managers have succeeded with the problem as it is for them to have wrestled with it and developed the skills and intuition for how to meet the challenge successfully the next time around. One problem with predicting future success from past success is that managers can succeed for reasons not of their own making– and we often learn far more from our failures than our successes. Failure and bouncing back from failure can be critical courses in the school of experience. As long as they are willing and able to learn, doing things wrong and recovering from mistakes can give managers an instinct for better navigating through the minefield the next time around.

(Photo by Yuryz)

Successful companies have good processes in place: “Processes include the ways that products are developed and made and the methods by which procurement, market research, budgeting, employee development and compensation, and resource allocation are accomplished.”

Processes evolve as ways to complete specific tasks. Effective organizations tend to have processes that are aligned with tasks. But processes are not flexible and they’re not meant to be. You can’t take processes that work for an established firm and expect them to work in a new-growth venture.

The most important processes usually relate to market research, financial projections, and budgeting and reporting. Some processes are hard to observe. But it makes sense to look at whether the organization has faced similar issues in the past.

Values:

An organization’s values are the standards by which employees make prioritization decisions – those by which they judge whether an order is attractive or unattractive, whether a particular customer is more important or less important than another, whether an idea for a new product is attractive or marginal, and so on.

Employees at every level make prioritization decisions. At the executive tiers, these decisions often take the form of whether or not to invest in new products, services, and processes. Among salespeople, they consist of on-the-spot, day-to-day decisions about which customers they will call on, what products to push with those customers, and which products not to emphasize. When an engineer makes a design choice or a production scheduler puts one order ahead of another, it is a prioritization decision.

This brings up a crucial point:

Whereas resources and processes are often enablers that define what an organization can do, values often represent constraints– they define what the organization cannot do. If, for example, the structure of a company’s overhead costs requires it to achieve gross profit margins of 40 percent, a powerful value or decision rule will have evolved that encourages employees not to propose, and senior managers to kill, ideas that promise gross margins below 40 percent. Such an organization would be incapable of succeeding in low-margin businesses– because you can’t succeed with an endeavor that cannot be prioritized. At the same time, a different organization’s values, shaped around a very different cost structure, might enable it to accord high priority to the very same project. These differences create the asymmetries of motivation that exist between disruptors and disruptees.

Acceptable gross margins and cost structures co-evolve. Another issue is how big a business opportunity has to be. A huge company may not consider interesting opportunities if they’re too small to move the needle. However, a wisely run large company will set up small business units for which smaller opportunities are still meaningful.

In the start-up stage, resources are important, especially people. A few key people can make all the difference.

(Photo by Golloween)

But over time, processes and values become more important. Many hot, young companies fail because the founders don’t create the processes and values needed to continue to create successful innovations.

As processes and values become almost subconscious, they come to represent theculture of the organization. When a few people are still important, it’s far easier for the company to change in response to new problems. But it becomes much more difficult when processes and values are established, and more difficult still when the culture is widespread.

Executives who are building new-growth businesses therefore need to do more than assign managers who have been to the right schools of experience to the problem. They must ensure that responsibility for making the venture successful is given to an organization whose processes will facilitate what needs to be done and whose values can prioritize those activities.

MANAGING THE STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

In every company, there are two strategy-making processes– deliberate and emergent. Deliberate strategies are conscious and analytical.

Emergent strategy… is the cumulative effect of day-to-day prioritization and investment decisions made by middle managers, engineers, salespeople, and financial staff. These tend to be tactical, day-to-day operating decisions that are made by people who are not in a visionary, futuristic, or strategic state of mind. For example, Sam Walton’s decision to build his second store in another small town near his first one in Arkansas for purposes of logistical and managerial efficiency, rather than building it in a large city, led to what became Wal-Mart’s brilliant strategy of building in small towns discount stores that were large enough to preempt competitors’ ability to enter. Emergent strategies result from managers’ responses to problems or opportunities that were unforeseen in the analysis and planning stages of the deliberate strategy-making process.

(Photo by Alain Lacroix)

If an emergent strategy proves effective, it can be transformed into a deliberate strategy.

Emergent processes should dominate in circumstances in which the future is hard to read and in which it is not clear what the right strategy should be. This is almost always the case during the early phases of a company’s life. However, the need for emergent strategy arises whenever a change in circumstances portends that the formula that worked in the past may not be as effective in the future. On the other hand, the deliberate strategy process should be dominant once a winning strategy has become clear, because in those circumstances effective execution often spells the difference between success and failure.

Initiatives that receive resources are strategic actions, and strategies evolve based on the results of strategic actions.Resource allocation decisions are especially influenced by a company’s cost structure – which determines gross profit margins – and by the size of a given opportunity. A great opportunity for a small company – or a small unit – might not move the needle for a large company.

Additional influences on resource allocation include the sales force’s incentive compensation system. Salespeople decide which customers to focus on and what products to emphasize. Customers, by their preferences, have significant influence on the resource allocation process. Competitors’ actions are also important.

The resource allocation process, in other words, is a diffused, unruly, and often invisible process. Executives who hope to manage the strategy process effectively need to cultivate a subtle understanding of its workings, because strategy is determined by what comes out of the resource allocation process, not by the intentions and proposals that go into it.

(Illustration by Amir Zukanovic)

In 1971, by chance Intel invented the microprocessor during a funded development project for a Japanese calculator company, Busicom. But DRAMs, not microprocessors, continued to represent the bulk of the company’s sales through the 1970s. By the early 1980s, DRAMs had the lowest profit margins of Intel’s products.

Microprocessors, by contrast, because they didn’t have much competition, earned among the highest gross profit margins. The resource allocation process systematically diverted manufacturing resources away from DRAMs and into microprocessors. This happened automatically, without any explicit management decisions. Senior management continued putting two-thirds of the R&D budget into DRAM research. By 1984, senior management realized that Intel had become a microprocessor company.

Intel needed both emergent and deliberate strategies:

A viable strategic direction had to coalesce from the emergent side of the process, because nobody could foresee clearly enough the future of microprocessor-based desktop computers. But once the winning strategy became apparent, it was just as critical to Intel’s ultimate success that the senior management then seized control of the resource allocation process and deliberately drove the strategy from the top.

It’s essential for start-ups to be flexible and adaptive:

Research suggests that in over 90 percent of all successful new businesses, historically, the strategy that the founders had deliberately decided to pursue was not the strategy that ultimately led to the business’s success. Entrepreneurs rarely get their strategies exactly right the first time… One of the most important roles of senior management during a venture’s early years is to learn from emergent sources what is working and what is not, and then to cycle that learning back into the process through the deliberate channel.

Once managers hit upon a strategy that works, then they must focus on executing that strategy aggressively.

The authors highlight three points of executive leverage on the strategy process. Managers must:

- Carefully control the initial cost structure of a new-growth business, because this quickly will determine the values that will drive the critical resource allocation decisions in that business.

- Actively accelerate the process by which a viable strategy emerges by insuring that business plans are designed to test and confirm critical assumptions using tools such as discovery-driven planning.

- Personally and repeatedly intervene, business by business, excercising judgment about whether the circumstance is such that the business needs to follow an emergent or deliberate strategy-making process. CEOs must not leave the choice about strategy process to policy, habit, or culture.

Managers have to pay particular attention to the initial cost structure of the business:

The only way that a new venture’s managers can compete against nonconsumption with a simple product is to put in place a cost structure that makes such customers and products financially attractive. Minimizing major cost commitments enables a venture to enthusiastically pursue the small orders that are the initial lifeblood of disruptive businesses in their emergent years.

THERE IS GOOD MONEY AND THERE IS BAD MONEY

The type and amount of money determines investor expectations, which in turn heavily influence the markets and channels the venture can and cannot target. Many potentially disruptive ideas get turned into sustaining innovations, which generally leads to failure.

Christensen and Raynor hold that the best money in early years ispatient for growth butimpatient for profit. Disruptive markets start out small, which is why patience for growth is important. Once a viable strategy has been identified, then impatience for growth makes sense.

Impatience for profit is important so that managers will test ideas as quickly as possible.

(Image by Vpublic)

It’s crucial to keep costs low for both low-end and new-market disruptive strategies. This determines the type of customers that are attractive.

Financial results do not signal potential stall points well. Financial results are the fruit of investments made years ago. Financial results tell you how healthy the business was, not how healthy the business is. Reliable data generally are about the past. They only help with planning if the future resembles the past, which is often only true to a limited extent.

Christensen and Raynor suggest three policies for keeping the growth engine running:

- Launch new growth businesses regularly when the core is still healthy – when it can still be patient for growth – not when financial results signal the need.

- Keep dividing business units so that as the corporation becomes increasingly large, decisions to launch growth ventures continue to be made within organizational units that can be patient for growth because they are small enough to benefit from investing in small opportunities.

- Minimize the use of profit from established businesses to subsidize losses in new-growth businesses. Be impatient for profit: There is nothing like profitability to ensure that a high potential business can continue to garner the funding it needs, even when the corporation’s core business turns sour.

THE ROLE OF SENIOR EXECUTIVES IN LEADING NEW GROWTH

Christensen and Raynor:

The senior executives of a company that seeks repeatedly to create new waves of disruptive growth have three jobs. The first is a near-term assignment: personally to stand astride the interface between disruptive growth businesses and the mainstream businesses to determine through judgment which of the corporation’s resources and processes should be imposed on the new business, and which should not. The second is a longer-term responsibility: to shephard the creation of a process that we call a “disruptive growth engine,” which capably and repeatedly launches successful growth businesses. The third responsibility is perpetual: to sense when the circumstances are changing, and to keep teaching others to recognize these signals. Because the effectiveness of any strategy is contingent on the circumstance, senior executives need to look to the horizon (which often is at the low end of the market or in nonconsumption) for evidence that the basis of competition is changing, and then initiate projects and acquisitions to ensure that the corporation responds to the changing circumstance as an opportunity for growth and not as a threat to be defended against.

The personal involvement of a senior executive is one of the most crucial things for a disruptive business. Often the most important improvements for the entire corporation begin as disruptions.

The vast majority of companies that successfully caught a disruptive innovation are companies still run by founders.

We suspect that founders have an advantage in tackling disruption because they not only wield the requisite political clout but also have the self-confidence to override established processes in the interests of pursuing disruptive opportunities. Professional managers, on the other hand, often seem to find it difficult to push in disruptive directions that seem counterintuitive to most other people in the organization.

BOOLE MICROCAP FUND

An equal weighted group of micro caps generally far outperforms an equal weighted (or cap-weighted) group of larger stocks over time. See the historical chart here: https://boolefund.com/best-performers-microcap-stocks/

This outperformance increases significantly by focusing on cheap micro caps. Performance can be further boosted by isolating cheap microcap companies that show improving fundamentals. We rank microcap stocks based on these and similar criteria.

There are roughly 10-20 positions in the portfolio. The size of each position is determined by its rank. Typically the largest position is 15-20% (at cost), while the average position is 8-10% (at cost). Positions are held for 3 to 5 years unless a stock approachesintrinsic value sooner or an error has been discovered.

The mission of the Boole Fund is to outperform the S&P 500 Index by at least 5% per year (net of fees) over 5-year periods. We also aim to outpace the Russell Microcap Index by at least 2% per year (net). The Boole Fund has low fees.

If you are interested in finding out more, please e-mail me or leave a comment.

My e-mail: jb@boolefund.com

Disclosures: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed.No part of this article may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission of Boole Capital, LLC.